For the last few weeks, Madagascar has been facing a particularly severe outbreak of pneumonic plague, which is mainly affecting the major urban centers of Antananarivo and Toamasina. Every year, between 250 and 500 cases are reported on the island. This year, the outbreak has occurred earlier than usual and touched urban areas, which increases the risk of transmission. The Institut Pasteur in Madagascar is on the front line, with support from the Institut Pasteur in Paris.

At the origin of the epidemic

A patient, who died on August 28, 2017 during a trip to his home city of Toamasina having passed through the capital Antananarivo, has been identified as the source of the plague outbreak in Madagascar. The outbreak alert was issued on September 11, following the death of a person in a hospital in Antananarivo (WHO source). Since then, a response has been organized to tackle the public health emergency and curb the spread of the outbreak. Alongside the health authorities, the Institut Pasteur in Madagascar – a WHO Collaborating Center for Reference & Research on Plague, which houses the Central Plague Laboratory – plays a key role in producing diagnostic tests, confirming results and carrying out epidemiological and bacteriological monitoring.

Follow the analysis of biological results notified to the Institut Pasteur in Madagascar

The Institut Pasteur in Madagascar plays a key role in producing rapid diagnostic tests, which are made available to hospitals and health centers free of charge.

What is so different about the 2017 plague outbreak in Madagascar?

For the second year in a row, the outbreak began in August, which is early. In addition, the majority of patients are presenting with pneumonic plague, the most contagious and deadly form of the disease. For instance, in 2016, we recorded 283 cases of plague, 12% of which were pneumonic. Finally, the outbreak this year mainly concerns urban foci in Toamasina and Antananarivo, where there is a high population density. This partly explains why it has spread so rapidly. As regards bacteriology, we have already isolated 8 strains of Yersinia pestis. Our tests show that they are susceptible to antibiotics recommended by the national plague control program. We are currently in contact with the Institut Pasteur in Paris, which will help us sequence these strains and identify any differences with those that circulated in previous years. We will then see what we can learn, if anything.

What is being done to contain the outbreak?

Priority is being given to early diagnosis so that patients can be treated immediately and isolated, and preventive treatment can be given to close contacts. The Institut Pasteur in Madagascar plays a key role in producing rapid diagnostic tests, which are made available to hospitals and health centers free of charge. They can be used to detect infection at the patient's bedside in under 30 minutes. To date, we have distributed close to 800 dipstick tests and are currently producing new ones.

Once diagnosis has been made, patients are immediately given antibiotics. It is also essential to carry out thorough investigations to identify contacts, i.e. anyone who came within two meters of the patient 48 hours before the onset of clinical signs and up to 48 hours after the start of treatment. All these people must also be treated to prevent the disease and stop the chain of infection.

What factors can be used to monitor the development of the outbreak?

For the moment, we must look at epidemiological indicators, the number of new cases and the mortality rate. Doctors and the general public are now very aware of the disease and patients should be diagnosed and treated rapidly. Information is also being given out about burial rituals. In Madagascar, remains are sometimes touched but the risk of infection persists. In addition, funerals can increase the risk of contact with contagious individuals, and people can travel from different regions in Madagascar and fuel the outbreak.

Alongside the Ministry of Public Health and with the help of experts from the Institut Pasteur in Paris, we are going to start analyzing epidemiological data in the next few days to model the outbreak. We will then have predictive indicators for a greater insight into its development, for example knowing when the outbreak peak will be reached, particularly in the cities. This data will enable the health authorities to tailor the response in the coming weeks.

Dipstick tests to diagnose plague in 15 minutes

Rapid tests, produced by the Institut Pasteur in Madagascar, are used to accurately diagnose plague in 15 minutes during an initial consultation, and appropriate care and prevention measures can therefore be adopted immediately. These dipstick tests – the result of research carried out with the Institut Pasteur in Paris and published in 2003 – detect the presence of a specific plague bacillus antigen, the F1 antigen, from sputum (pneumonic plague) or boils (bubonic plague). They can also be used to detect plague in rats. Every year, the Institut Pasteur in Madagascar produces around 5,000 dipstick tests and supplies health facilities free of charge if required.

Cooperation between the Institut Pasteur in Madagascar and in Paris

- Plague diagnosis

Clinical diagnosis of plague is based on patient symptoms and relevant history, such as travel to an endemic region or contact with a plague patient. Following rapid diagnosis, the samples are sent to the Central Plague Laboratory at the Institut Pasteur in Madagascar. A second rapid test is carried out followed by a PCR, which is used to directly detect the bacterium’s DNA.

The Laboratory for Urgent Response to Biological Threats (page in French) at the Institut Pasteur (Paris) is sending two technicians to the Institut Pasteur in Madagascar in October 2017 to bolster the laboratory teams, given the high number of cases to be confirmed. These technicians will also help set up the real-time PCR technique, which is used to obtain a diagnosis in roughly 6 hours, rather than the current 24 hours.

- Monitoring the development of the outbreak

"Extensive detection and monitoring work is performed in the field", points out Simon Cauchemez, who heads up the Mathematical Modeling of Infectious Diseases Unit at the Institut Pasteur in Paris. "This work is backed up by data analysis, which is required to understand what is happening, where the cases have been reported, if they are under control, etc." Two team members from Simon Cauchemez's unit will travel to Madagascar to analyze data collected about the 2017 outbreak. "We're going to help the Institut Pasteur in Madagascar carry out these analyses, make the best use of the data and describe the outbreak, to advise the government and WHO on the best response." The unit is lending its experience, as it did in Martinique when the Zika outbreak hit the entire American continent in 2015-2016 (read in french the Modeling to monitor and anticipate the Zika outbreak in Martinique) article.

Plague, an endemic infection in Madagascar

"Plague is still rife in Africa, Asia and America, and is counted among the world's re-emerging diseases", reports the Institut Pasteur (Paris) fact sheet on plague. Nearly 50,000 human cases of plague were reported to the World Health Organization (WHO) by 26 countries in Africa, Asia and America between 1990 and 2015. Sub-Saharan Africa is currently the most affected region, with the Democratic Republic of Congo, Uganda and above all Madagascar, which reports the highest number of human cases of plague in the world (between 250 and 500 cases a year). Plague arrived on the island in 1898, via the port of Toamasina, following the stop-over of a boat from India. It was brought under control in the 1930s but remained silently in rural areas before re-emerging in the 1980s. This zoonosis mainly affects the central highlands over 800 meters in altitude, with rural foci and an urban focus in Antananarivo. There is also a coastal urban focus in Mahajanga, in the northwest of the island. In the mountainous regions, the human plague season is from October to April, but in the Mahajanga region, it runs from July to November. Furthermore, plague circulates in rats via fleas in sylvatic foci.

Although the most common bubonic form is contracted via flea bites, the much more serious pneumonic form is spread through the air – when the bacillus reaches the lungs, it is transmitted by saliva droplets expelled by patients when they cough. If appropriate early treatment is not administered, pneumonic plague is always fatal within three days.

"The incubation period for the pneumonic form is very short, from a few hours to a maximum of two days", explains Anne-Sophie Le Guern, Head of the National Reference Center for Plague and other Yersinia Infections (page in French) at the Institut Pasteur in Paris. "Patients therefore develop symptoms very quickly. As a National Reference Center, here at the Institut Pasteur we work alongside Santé publique France to decide in which situations a case of plague is suspect or probable. We have also updated an information sheet for the ambulance service and front-line health care workers, particularly on Mayotte or Reunion, when a patient arrives in hospital."

The COREB fact sheet for Plague (page in French)

NB : The COREB fact sheet for Plague, drawn up at the request of the Directorate General for Health in case the emergency services are brought in, and hosted by the French Language Infectious Disease Society (SPILF). COREB mission, or SPILF-COREB group (Network operational coordination of epidemic and biological risk).

Plague fact sheet

Research on plague at the Institut Pasteur in Madagascar

Multidisciplinary studies are being conducted at the Institut Pasteur in Madagascar to gain a holistic understanding of the disease by looking at the bacterium, vector flea, rodents and humans at the same time. So, in addition to the Plague unit, the Entomology, Immunology and Epidemiology units are also involved.

As for diagnosis, there is a project focused on developing a method for detecting Yersinia pestis directly from biological samples, using the simple and inexpensive LAMP technique. Another program aims to identify resistant bacteria by analyzing the spectrum of volatile molecules produced when these bacteria are crushed. In humans, there is a project aiming to characterize the immune response of individuals who have been infected with plague but have not developed symptoms.

A project is underway in rural areas to compare the effectiveness of spraying insecticide, the current reference method, with the use of Kartman bait boxes, which combine a slow-acting rodenticide with a fast-acting insecticide in the same container. This technique is used to fight fleas and rats at the same time.

Finally, further research focuses on plague monitoring, rodent zoonoses and the Xenopsylla cheopis vector flea.

Research on plague at the Institut Pasteur in Paris

The work of the Yersinia research unit primarily focuses on analyzing:

- mechanisms used by Yersinia to acquire virulence factors,

- comparative genomics and transcriptomics between Y. pestis and Y. pseudotuberculosis,

- molecular bases for the exceptional pathogenicity of Y. pestis,

- mechanisms of innate and adaptive immunity in the host,

- antibiotic resistance in pathogenic Yersinia,

- evolution of pathogenic Yersinia.

The Yersinia unit is also developing:

- a bubonic and pneumonic plague vaccine. A vaccine candidate was patented in 2014. The next step involves preclinical trials,

- real-time in vivo imaging technology to study the kinetics of Y. pestis development in its host,

- tools for gene complementation and gene expression in vitro and in vivo,

- techniques for molecular characterization of the various Yersinia species.

The unit plays an active role in monitoring and controlling enteropathogenic Yersinia through its activities at national level (National Reference Center -page in French- and National Surveillance Network) and in the fight against plague at international level (World Health Organization Collaborating Center, or WHOCC -page in French-).

Public health response

The Madagascan health authorities are organizing the response in terms of care alongside WHO and the CDCs. On October 6, 2017, WHO announced it had supplied 1.2 million doses of antibiotics to fight plague in Madagascar. "If detected in time, plague is a treatable disease, declared Dr. Charlotte Ndiaye, WHO representative in Madagascar. Our teams ensure that all those at risk have access to protection methods and treatment." 244,000 additional doses are expected in the coming days.

"The various types of drug will be used for curative and prophylactic purposes. The shipped doses can be used to treat up to 5,000 patients and protect up to 100,000 people who may have been exposed to the disease." Bubonic and pneumonic plague can be treated if standard antibiotic therapy is given early. Antibiotics can also prevent the infection in people who have been exposed to plague

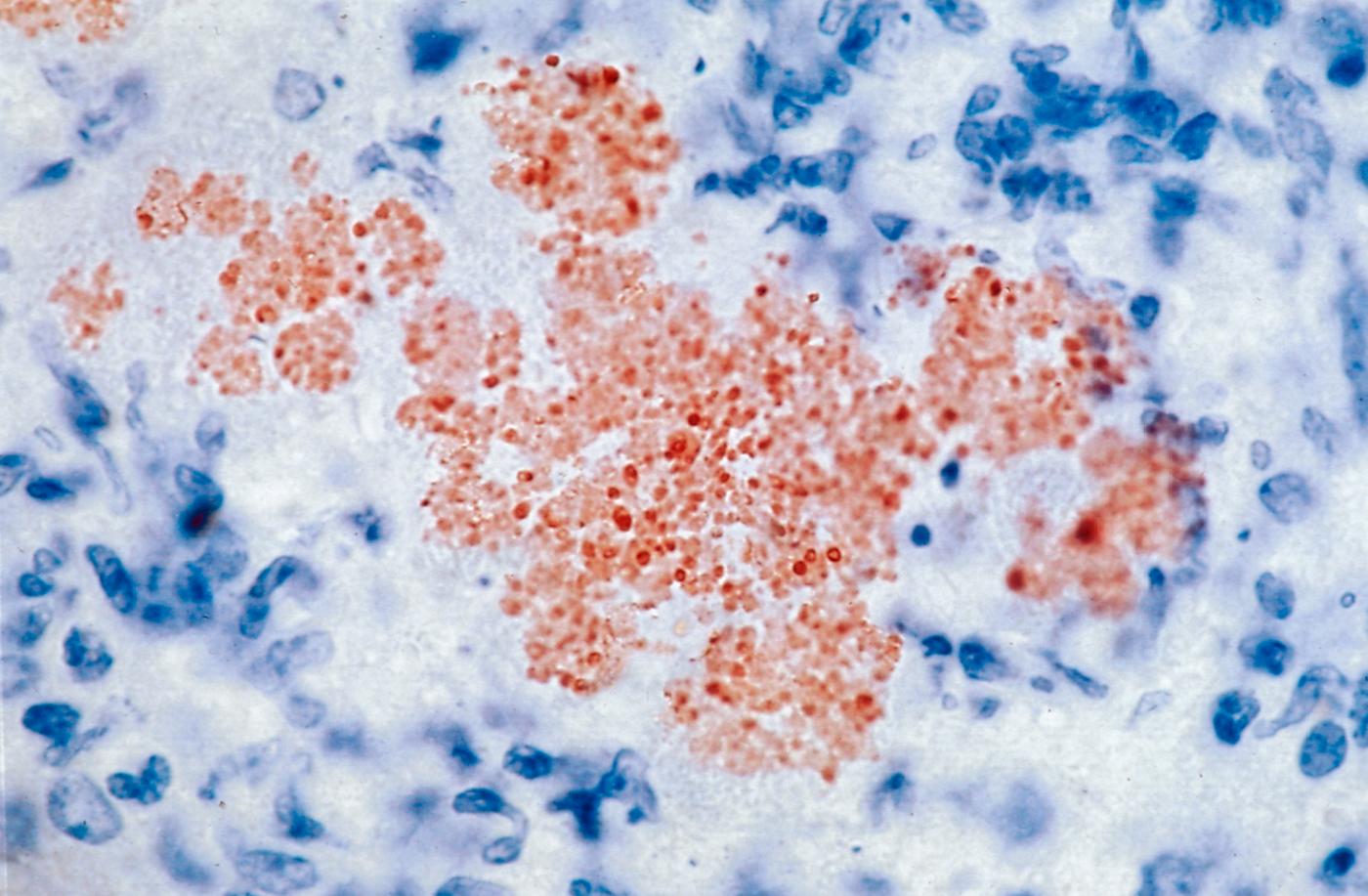

Mouse liver infected with the plague bacillus Yersinia pestis. © Institut Pasteur

Plague, a constant and recurrent topic at the Institut Pasteur in Madagascar

The history of the Institut Pasteur in Madagascar is inextricably linked to the endemic plague on the island. It was in 1898, the year the institute was founded, that the first cases of plague emerged in Toamasina. It remained confined there until 1921, when it spread to Antananarivo and the central highlands causing unprecedented outbreaks for nearly 20 years (Ratsitorahina M & Al, 2002). The government then turned to the Institut Pasteur for help in fighting plague. A large number of research programs were launched and the topic has continued to dominate research at the institute ever since.

In 1932, Georges Girard, Director of the Institut Pasteur in Madagascar and Jean Robic, his deputy, developed the first effective plague vaccine called EV. The vaccination method, used extensively in the central highlands, brought spectacular results as early as 1935, reducing plague cases to under 200 a year compared with around 3,500 to 3,600 cases previously. The plague was under control even though it still remained. The vaccine was widely used, including in other parts of the world (South Africa, Belgian Congo, USSR) before the discovery of streptomycin, an antibiotic that is still used today and which radically changed the way plague was treated.

Alexandre Yersin isolated the Yersinia pestis plague bacillus on June 20, 1894

Alexandre Yersin was appointed by the French government to deal with the plague outbreak devastating Yunnan in China in 1894. Once in the country, and despite competition from the Japanese team, he discovered the agent responsible, Yersinia pestis, which bears his name and which he described as: "small stocky spindles with rounded ends".