“Epidemics, pandemics, an endless story?”: a question for research, citizens and society

The aim of this text is not to provide full proceedings of the conference but to look back at some of the main examples presented during the day.

Watch the conference in full “Épidémies, pandémies : une histoire sans fin ?”, held on December 7, 2022 at the Institut Pasteur.

On December 7, 2022, after three years of the COVID-19 pandemic and at a time when climate change is threatening to speed up the emergence of new viruses, the Institut Pasteur held a conference entitled Epidemics, pandemics: a never-ending story? under the high patronage of French President Emmanuel Macron. The conference was open to the public, and the scientific program was set by two experts from the Institut Pasteur: Pascale Cossart, a biologist specializing in cellular microbiology and a member of the French Academy of Sciences since 2002; and Olivier Schwartz, a virologist and Head of the Institut Pasteur's Virus and Immunity Unit. Emerging infectious diseases remain a highly topical issue, one which has been thrust even further into the spotlight with the COVID-19 pandemic. And the issue is not just one for epidemiologists: social, economic and political contexts also play a part in the severity and duration of disease outbreaks. That is why a multidisciplinary One Health approach, which involves monitoring the environment and animal and human populations, represents our greatest hope for understanding, preventing and curbing future epidemics and pandemics.

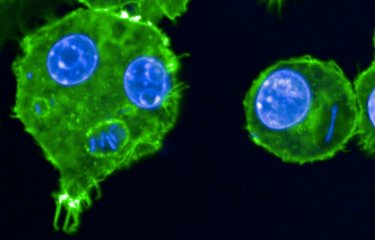

Plague, flu, tuberculosis, malaria, AIDS, COVID-19… the intersecting views of bacteriologists, virologists, parasitologists, epidemiologists, anthropologists, geneticists and veterinarians have led to a better understanding of past and current epidemics, and to learn lessons to arm ourselves against future epidemics in an era of globalization and global warming. Copyright: Institut Pasteur/ François Gardy.

At the conference, addresses given by the Minister for Higher Education and Research and the Minister for Health and Prevention emphasized the inextricable links between excellence in research and public health challenges.

The Minister for Higher Education and Research, Sylvie Retailleau, opened the session by insisting on "the need for a more coordinated response to health crises." She also mentioned the importance of "restoring confidence in science at a time when fake news and conspiracy theories are circulating widely." Finally, she pointed out that the health crisis we have just lived through was a challenge "for mental health, especially for vulnerable people."

Are there any viable solutions, or are epidemics and pandemics a never-ending story? In underscoring the need to enlighten and inform, to disentangle fact from fiction and offer a rational approach, the conference at the Institut Pasteur reflected the spirit of its founder, Louis Pasteur, as celebrations are held to mark the bicentenary of his birth.

Pandemics in the 20th century and their legacy

Several contributions looked back at the long history of epidemics. The conference subheading, "A never-ending story," is particularly apt: not only is it difficult to precisely pinpoint the end of an epidemic or pandemic (resurgences are always a possibility, as we were reminded by Philippe Sansonetti, a microbiologist, Professor Emeritus at the Institut Pasteur and the Collège de France and Member of the French Academy of Sciences); it is also inevitable that further outbreaks will continue to emerge.

- Read Emergence, an inevitable and unpredictable fact of life, by Jean-Claude Manuguerra, Head of the Environment and Infectious Risks Unit at the Institut Pasteur

Patrick Berche, former President of the Institut Pasteur de Lille, even added that pandemics (epidemics on a global scale) are not a new phenomenon; humanity has been dealing with them ever since the Neolithic period. Primates, rodents, bats, birds, pets and livestock have historically been the starting point for most emerging infectious diseases. Antoine Gessain, Head of the Oncogenic Virus Epidemiology and Pathophysiology Unit, pointed out that 70% of emerging infectious diseases are zoonoses. Animal reservoirs and modes of transmission may vary but they are generally spread through contact with the body fluids of animals (blood, saliva, urine, etc.).

- See also Monkeypox: a detailed profile of the disease (with Antoine Gessain from the Institut Pasteur)

Diseases and other social and environmental factors can work in synergy to produce even more harmful effects, creating what is referred to as a syndemic. HIV/AIDS and COVID-19 are examples of syndemics, both diseases persisting in part because of inequalities in access to healthcare.

Epidemic, censure and political conflicts

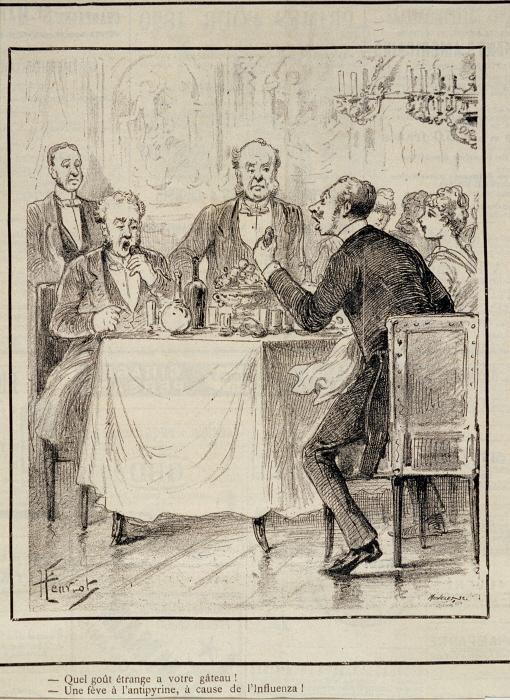

Laura Spinney, a scientific journalist and novelist, is a specialist in the 1918 influenza pandemic known as the Spanish flu. The author of the book Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How it Changed the World spoke about the human impact of this historic pandemic. During the First World War, there was widespread press censure about the epidemic in a bid to strengthen the war effort. Spain was not involved in the conflict and was the only European country to allow newspapers to report on the outbreak, which led to the disease being dubbed "Spanish flu." In reality, however, sources suggest that it began in Kansas (United States), Britain or France. If we take into account the most vulnerable populations, the number of deaths is likely to have easily reached the 100 million mark, much higher than the often reported official figure of 24 to 30 million.

- See also 1918-2018 – the hundredth anniversary of the "Spanish" flu pandemic

"What a strange taste your cake has!"

"An antipyrine bean, because of influenza!”

Lessons from the COVID crisis for other diseases

The COVID-19 pandemic – which is not yet over – had far-reaching consequences, especially in health and social terms. It also had an ambivalent impact on the management of endemic diseases. And it turned the field of science on its head: research efforts largely switched to projects related to COVID-19, to the detriment of other diseases. The lockdowns imposed in several countries led to a forced interruption in non-COVID research projects at global level. This enforced break brought a brutal halt to the progress being made in research on HIV and other diseases. Although research gradually returned to normal, the question then arose as to how the funding allocated to scientific projects should be distributed. What research activities should be supported as a matter of priority in the pandemic context of COVID-19, given that HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria, among many other diseases, are continuing to claim hundreds of thousands of lives each year?

Although coordinating responses to multiple microbial threats proved to be a tricky task, the COVID-19 crisis was also a time when technological development moved up a gear. The large-scale rollout of vaccination based on messenger RNA (mRNA) broadly mitigated the health consequences of COVID-19. The preliminary results of an mRNA vaccine for HIV currently appear to be "very disappointing," according to Françoise Barré-Sinoussi, a French virologist and laureate of the 2008 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for her discovery of HIV at the Institut Pasteur in 1983. But the COVID-19 pandemic has potentially opened up a new era in therapeutic approaches to infectious diseases. As well as treatments, the crisis also led to the introduction of innovative screening techniques, widespread use of self-testing and the first steps into telemedicine – all of which are tools that could be applied to other diseases in future.

For, as Philippe Sansonetti reminded us by quoting Charles Nicolle, "there will always be new diseases – that is a fatal truth." The health emergency that we are currently experiencing should improve our preparedness for future disease outbreaks. Imposed lockdowns proved to be effective in limiting the spread of the virus, especially those introduced at an early stage. Arnaud Fontanet, Head of the Institut Pasteur's Epidemiology of Emerging Diseases Unit, pointed out that the countries which implemented early lockdowns were able to lift their lockdown measures more quickly. "It's not health versus the economy. It's health with the economy," he explained, emphasizing that the socio-economic consequences of the epidemic should not be seen in opposition to its health consequences; rather the two impacts went hand in hand. Sylvie Retailleau and François Braun also reiterated the vital importance of epidemiological modeling for public authorities. Although this approach is not yet perfect, in an unprecedented pandemic context it proved its worth, especially in anticipating rising patient numbers in hospitals.

- See also the book Tempête parfaite [A Perfect Storm] by Philippe Sansonetti

- See also COVID-19: Chronicle of an expected pandemic / Exiting lockdown

Ethical, economic and social challenges

Frédérick Keck, Director of the Laboratory of Social Anthropology (Collège de France, CNRS, EHESS), spoke about avian influenza, caused by the virus H5N1. This severe disease affects several bird species (including farmed birds), but very rarely humans. The scientist particularly highlighted the sometimes contradictory challenges that need to be dealt with when tackling such outbreaks. One solution is to eliminate animals that are known or thought to be infected. But culling an entire flock represents a considerable loss for poultry farmers and traditional open-air farming (not to mention the psychological impact on farmers). These radical responses, and the idea that wild birds suspected of being contaminated should also be culled, have also attracted the ire of animal rights activists, who condemn the fact that so many birds should die simply to maintain profits. Vaccinating poultry is an alternative solution that could be applied in theory, but it may encourage the development of resistant strains. Exporting vaccinated poultry also raises legislative hurdles, and consumers would be less likely to want to eat vaccinated poultry.

Why are populations susceptible to certain infections?

What impact has natural selection had on immunity genes? How does a population that arrives in a new area adapt to its new environment? For Lluis Quintana Murci, Head of the Institut Pasteur's Human Evolutionary Genetics Unit, it does so rapidly by "admixing with the local population." The Bantu people brought malaria to Pygmy populations, but they also gave them a resistance gene.

- See also New research suggests earlier emergence of malaria in Africa

Studying ancient DNA can therefore provide us with a huge amount of information to help us understand the susceptibility of populations to certain infections. Research carried out in 2016, for example, showed that there is indeed a difference in the way populations respond to infection; moreover, this response is largely controlled by genetics, with natural selection playing an important role in shaping our immune profiles. The research also offered proof that the genetic legacy passed on by Neanderthals to Europeans has significantly influenced their ability to protect themselves from viruses.

Innovative approaches to tackle malaria and multidrug resistance

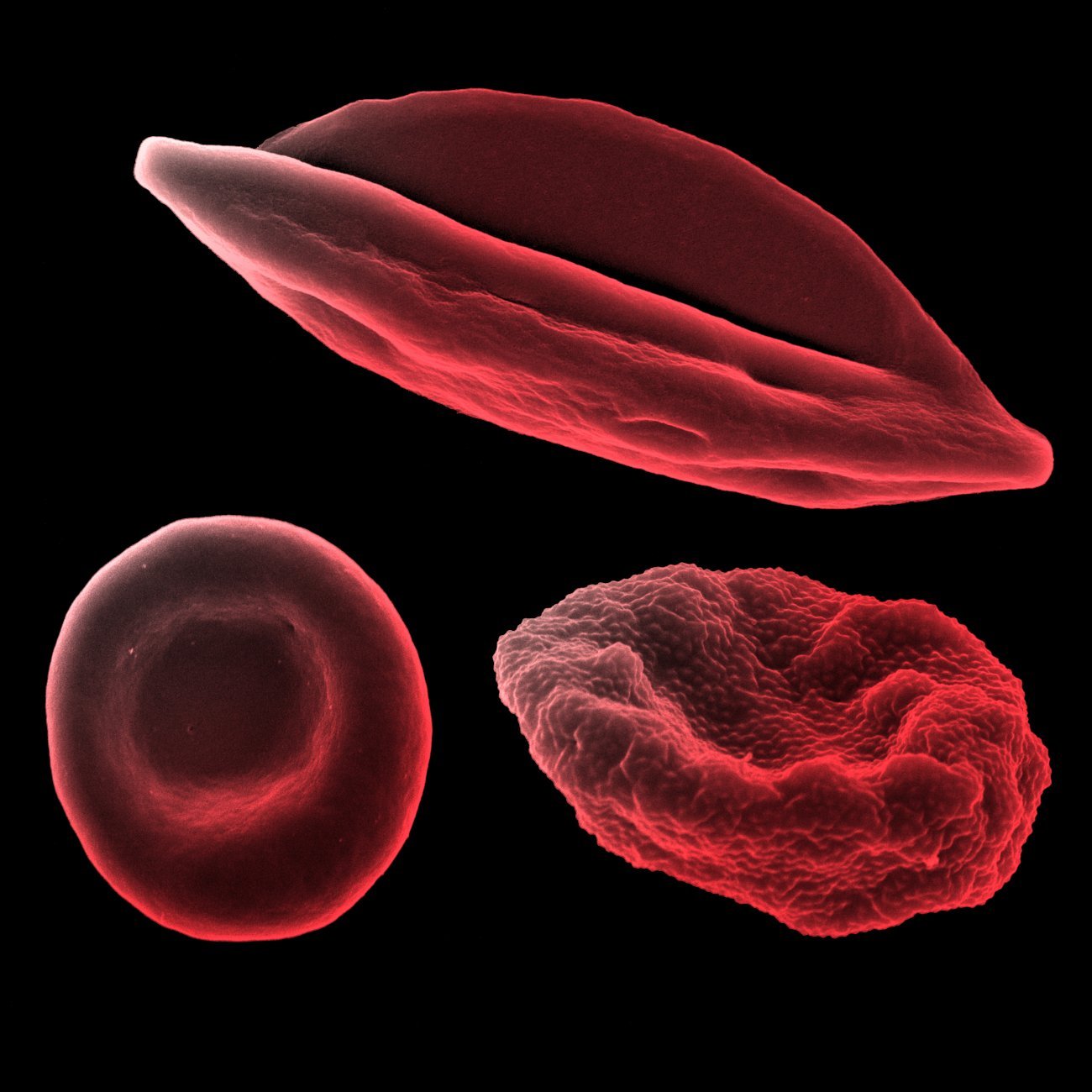

Malaria is the most deadly parasitic disease, claiming nearly half a million lives each year worldwide. Odile Mercereau-Puijalon, currently a visiting scientist at the Institut Pasteur, spoke about Plasmodium falciparum, the most widespread and dangerous malaria agent, thought to have been transmitted from monkeys to humans around 35,000 years ago and to have adapted to its new host over time.

Eradicating the malaria epidemic is not an easy task. Prevention involves killing vector mosquitoes using insecticides, but resistant individuals are emerging. Chloroquine, a drug commonly used from the 1950s onwards to eliminate the parasite, has since been replaced by artemisinin, which is less toxic and much more effective – but Plasmodium is now starting to develop resistance to these drugs. Vaccines are only relatively effective (30 to 40%). Since 2015, several attempts to eliminate the epidemic have ended in failure, with the number of infected individuals worldwide remaining relatively stable.

New vaccines are being developed to prevent less dangerous types of Plasmodium, P. vivax and P. chitnis, from entering red blood cells, and these vaccines could be adapted to tackle P. falciparum infection over the long term. Scientists have also observed that mutations in some genes have a negative impact on human hemoglobin and make it less easy for the parasite to use. Clarifying the effects of these mutations represents an original and promising avenue for the development of genetics-based treatments.

- See also Malaria: blood stage of the parasite recreated in vivo to help tackle the disease

- See also A new drug target against malaria

Human red blood cell (bottom left), human red blood cell infected with Plasmodium falciparum schizonte (bottom right) and human red blood cell infected with Plasmodium falciparum gametocyte IV (top), observed under scanning electron microscope. Research Unit: Biology of Host-Parasite Interactions.

Copyright: Institut Pasteur/Aurélie Claës - colorization Jean-Marc Panaud

How to prevent and tackle epidemics

More than half of all threats to human health today continue to be infectious diseases – even bearing in mind that non-biological factors such as wars, pollution and climate events can also have an impact on health.

According to Philippe Sansonetti, a pandemic often develops in three successive stages: emergence of the disease, expansion and finally regression. A pandemic can regress in two ways: either the disease is brought under control through treatment without being eradicated (medical end) or populations learn to live with a disease that is now part of their daily lives (social end). It is rare to see a pandemic brought to a permanent end at planetary level, as countless geographical and socio-demographic factors make it complicated to monitor and control diseases.

There have been some exceptions, however. The smallpox virus was officially eradicated in 1980, although not without difficulty and false hopes along the way. SARS-CoV-1, responsible for the SARS outbreak, was isolated in the space of a few months without causing an epidemic thanks to the application of a very strict "test, trace, isolate" protocol in patients suspected of being infected. These historical examples demonstrate the importance of acting quickly and rigorously to tackle emerging infectious diseases.

Decisions taken by major institutions such as the World Health Organization (WHO) play a key role in controlling disease outbreaks. When WHO prematurely announced that the Ebola epidemic had come to an end, vaccine campaigns and aid to underdeveloped countries were suspended, leaving the door open for a resurgence of the epidemic. The same error was previously made with Spanish flu and would subsequently be made again with COVID-19. But even if the best decisions are taken, eliminating COVID-19, for example, would require at least 90% of the world's population to be vaccinated (similar to the current rate for measles), which represents a considerable humanitarian and logistical challenge.

The question of monitoring infectious diseases in populations was also addressed at the conference. Such surveillance is carried out even during non-pandemic periods (this is the role of National Reference Centers (CNRs) in France). Taking the example of the current COVID-19 pandemic, surveillance can help identify the emergence of variants. A significant research effort is required on top of surveillance to understand the mechanisms involved in the emergence of variants – and this topic continues to be the focus of much discussion, as explained by Etienne Simon-Lorière, Head of the Institut Pasteur's Evolutionary Genomics of RNA Viruses Unit.

Another example is the surveillance of mosquitoes, vectors of disease, as described by Anna-Bella Failloux, an entomologist and Head of the Institut Pasteur's Arboviruses and Insect Vectors Unit. Climate change and the intensification of human interactions are having an undisputed impact on ecosystems. Average temperature increases are also bringing about a rise in mosquito density, together with a progressive enlargement of the geographical areas where mosquitoes live and an extension in their periods of activity. Given these developments, the pathogens transmitted by mosquitoes are becoming potential sources of epidemics.

- See also the report A historic fight against emerging infectious diseases

Monitoring the environment and animal and human populations

Several speakers emphasized the importance of moving from an anthropocentric view to a more holistic view known as One Health, which suggests that we need to reconsider our relationship with the living world and study it more deeply to improve our understanding of disease outbreaks and anticipate the emergence of epidemics. This is particularly true as we recognize the need to tackle climate change and to consider the living world as a whole. Monique Eloit, Director General of the World Organization for Animal Health, discussed this integrated, unified approach, which aims to optimize the health of people, animals and ecosystems over the long term. She insisted on the fact that "human medicine and veterinary medicine must be interlinked." The One Health concept is obviously not new, but after several decades of increasingly targeted approaches, hyperspecialization has made us lose sight of the need for a more comprehensive approach – now more than ever.

- On the One Health concept, see also the section Welcome to the age of emergence

The consequences of health crises on our societies

Many experts at the conference also alluded to the reconfiguration of social interactions during epidemics. Why do some epidemics seem to be "forgotten," while others continue to occupy a prominent place in the political agenda? The key role of patient organizations was particularly highlighted. The COVID-19 pandemic also marked a new phase in the relationship between science and society. Although scientific controversies are an integral part of research, Françoise Barré-Sinoussi pointed out that in this case such controversies were largely exploited. Their airing on the public stage may have unnerved some people, especially during a confusing period in which the sheer volume of (true or false) information was skyrocketing.

Finally, pandemics should perhaps be seen first and foremost as social events. Taking the examples of HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis, the Institut Pasteur President, Stewart Cole, and Françoise Barré-Sinoussi emphasized in turn that disease outbreaks have a greater impact on fragile populations and only serve to impoverish them further. That is why it is so important to remember the humanist vision of Louis Pasteur, a vision that can be summed up as follows: solidarity, equity, and sharing knowledge.