The first cases of mpox were observed in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 1970, then spread to a number of other African countries. In the Central African Republic, the first case was recorded in the 1980s, in a family living in the south-west of the country. The Institut Pasteur de Bangui monitored this case and the subsequent ones, and has since developed expertise on the disease, so it was well positioned to sound the alarm when the first outbreaks occurred in Africa in 2017-2018. A large-scale study named Afripox was launched with the Institut Pasteur in Paris, which was already working on mpox. Read on to find out about the history of mpox and the recent findings of the study.

In August 2024, an imported case of mpox was confirmed in Sweden. Did this signal a return of mpox to Europe, like in 2022? And how did this disease, thought to be confined to forests in central Africa, come to be exported to other regions?

Emmanuel Nakouné, virologist at the Institut Pasteur de Bangui, explains in 2 minutes the history of mpox and recent discoveries © Institut Pasteur (video in french)

1970-2010: the first cases of mpox

2010-2016: a relative slowdown in mpox cases

Since 2017: spread of the virus through Africa

Afripox: a collaborative project to improve understanding of mpox

Five major discoveries about mpox

- Genital lesions: a little-known symptom

- An epidemiological transition from rural to urban areas

- An African squirrel, the most likely animal reservoir

- New diagnostic tests confirmed in the laboratory

- Sequencing methods under development

1970-2010: the first cases of mpox

First identified in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 1970, the disease has long been confined to a dozen African countries. The first case of mpox in the Central African Republic (CAR) was reported in 1984 after the observation of skin lesions typical of the disease. This case involved a family in south-west CAR who had hunted and eaten a monkey and a duiker (a small antelope) that had the monkeypox virus (MPXV), which causes mpox.

It was not until 2001 that the virus was virologically confirmed in the CAR by the Institut Pasteur de Bangui.

Until 2010, relatively few cases of mpox were reported in Africa, except in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). "From 2010 onwards, the DRC was reporting more than 1,500 cases each year," says Emmanuel Nakouné, a virologist at the Institut Pasteur de Bangui.

2010-2016: a relative slowdown in mpox cases

In the Central African Republic, local populations depend on hunting for animal protein. But over the decades, access to this source of animal protein has become increasingly difficult. Large game has become less abundant, and there has been a new trend towards hunting smaller animals, including rodents, some of which are thought to be an animal reservoir for mpox (see below).

In 2010, the CAR took the decisive step of making mpox a notifiable disease, thereby stepping up its surveillance of this emerging health threat. This resulted in better documentation and a more structured response to any new cases.

In 2012, the CAR began to experience a period of socio-political instability which led people to flee villages and take refuge in forests, and it is likely that this created favorable conditions for direct contact with animals that were potential carriers of MPXV, especially the small animals already suspected. "Despite the sporadic presence of medical groups like Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), it was hard to maintain continuity of care. MSF regularly sent me samples to confirm the diagnosis," says Emmanuel Nakouné. This enabled them to observe a link between the localization of forest populations and their proximity with animal reservoirs.

Between 2013 and 2016, a slowdown was observed, with an average of 5 to 10 cases a year in the CAR. In 2013, Emmanuel Nakoune decided to submit a research proposal (an "Inter-Pasteurian Concerted Action" or ACIP) to investigate the epidemiology of mpox. The research found that more than 50% of the population studied had antibodies against orthopoxviruses. Older people had developed these antibodies after being vaccinated for smallpox. As smallpox vaccination continued until 1980, this likely explains why mpox outbreaks were contained in villages.

The largest outbreak in the CAR over this period was in 2016, following the late detection of a case in a child. After an initial visit to a dispensary, the family had to travel to a regional hospital using various means of transport, which facilitated the spread of the virus to multiple contacts, including family members and medical staff without sufficient protection. A total of 13 people were infected from this one initial case. This outbreak revealed the shortcomings in the local health system.

Since 2017: spread of the virus through Africa

The year 2017 was a milestone in the epidemiology of mpox, with cases reported in regions that had not previously been affected. This geographical spread points to a likely extension of the distribution area for animal reservoirs.

In 2018, a significant outbreak in Nigeria drew international attention. In response, the World Health Organization (WHO) assembled the countries concerned and presented a detailed situation report for the disease. The Institut Pasteur de Bangui was subsequently appointed as a reference institute to boost surveillance capabilities in Central and West Africa, not just in the CAR but also in neighboring countries such as the Republic of the Congo.

Mpox (formerly known as monkeypox) is a disease caused by a virus historically found in Central and West Africa. Outbreaks have long been confined to forest regions near the habitat of its likely animal reservoir, thought to be among three species of rodents: the Lorrain dormouse (Graphiurus lorraineus), Gambian or giant pouched rat (Cricetomys gambianus) and Thomas’s rope squirrel (Funisciurus anerythrus, see below). The typical pattern is for children or young adults to become infected on coming into contact with these animals hunted for their meat, and to bring the virus into the household. The other family members contract the disease when they come into contact with the initial patient. "Transmission generally occurs through contact with skin lesions, which contain infectious viral particles, or with contaminated items, especially bedding," explains Antoine Gessain, a virologist at the Institut Pasteur. Clinical signs are a maculopapular rash, which may affect the soles of the feet and palms of the hands, and swollen lymph nodes.

Skin rash © Institut Pasteur de Bangui

Skin rash © Institut Pasteur de Bangui

The case fatality rate is thought to be between 1% and 10%. It depends on the age of the patient, with younger people being at greater risk of severe forms, as well as on available medical treatment (more complicated in remote areas) and whether the person is immunocompromised (for example from HIV). Mpox is diagnosed by PCR amplification of the viral genome based on samples from skin lesions. Treatment is symptomatic, with severe cases requiring rehydration, nutritional support and antibiotics to treat secondary bacterial infections of skin lesions. A specific antiviral drug, tecovirimat, has proven effective in animals and is currently being assessed in humans. There are vaccines developed for smallpox which are effective in treating mpox.

Dr Mbrenga Festus, the doctor in charge of treating mpox patients in Emmanuel Nakouné's department © Institut Pasteur de Bangui

Dr Mbrenga Festus, the doctor in charge of treating mpox patients in Emmanuel Nakouné's department © Institut Pasteur de Bangui

Afripox: a collaborative project to improve understanding of mpox

The Afripox project was launched in 2019 but soon had to be put on hold because of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the multi-country mpox outbreak in 2022 sparked renewed concern among health authorities and the scientific community, leading to the resumption of Afripox and its conclusion in 2024, with significant new discoveries.

The teams at the Institut Pasteur in Paris (Antoine Gessain, Arnaud Fontanet, Jean-Claude Manuguerra and Tamara Giles-Vernick) and the Institut Pasteur de Bangui (Emmanuel Nakouné) worked together on the Afripox project, which was funded by the French National Research Agency (ANR). They had several objectives:

- To gain a more detailed understanding of the conditions for the emergence of MPXV;

- To provide a more precise description of the clinical forms of mpox in an African context;

- To identify the animal reservoirs and secondary hosts of the virus;

- To improve diagnostic tests for use in remote areas;

- To understand the practices of local populations and their perception of the disease.

Genital lesions: a little-known symptom

Knowledge about the clinical profile of mpox has developed. Since 2021, physicians have followed a strict protocol when administering tecovirimat, a treatment used for mpox. Every day after administering the drug, they count the number of skin lesions. This led them to notice that in the vast majority of cases, patients had skin lesions near their genital organs. "This indicates possible transmission during sexual intercourse," explains Arnaud Fontanet. "It can even be considered as a high-risk behavior. These lesions could explain transmission between parents within the household," he adds.

An epidemiological transition from rural to urban areas

Mpox was historically confined to rural environments on the outskirts of forests (also known as peri-forest areas), with children becoming infected while hunting rodents. But the disease is increasingly found in built-up urban areas, where population density facilitates spread and where the virus is circulating among communities at high risk of sexual transmission, especially men who have sex with men (MSM) and sex workers. This transition was clear when observing the first cases in urban regions, for example in Nigeria and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), during Afripox. There is also now the added risk that the virus will be exported from people living in urban areas who are more likely to travel.

Given that the disease is now spreading to new regions, urban healthcare structures need to be thoroughly prepared to ensure that they can respond effectively in the event of an outbreak. Informing public authorities and training healthcare providers is crucial to avoid the virus spreading across continents.

An African squirrel, the most likely animal reservoir

The team led by Alexandre Hassanin at the French Museum of Natural History in Paris and the Oncogenic Virus Epidemiology and Pathophysiology (EPVO) team led by Antoine Gessain have contributed to research on viral reservoirs for mpox. They compared the ecological niche of MPXV with the ecological niches of the African mammals most likely to be infected. With the help of this information, they were able to analyze overlaps in ecological niches using modeling and create maps to identify which animal species is most likely to be the MPXV reservoir. The results showed that the Thomas’s rope squirrel (Funisciurus anerythrus) is probably the reservoir for MPXV. The species is found in the tropical rainforest areas of Central and West Africa.

The animal reservoir, the Funisciurus anerythrus squirrel © Mathias D'haen-GabonBiota.org portal

The animal reservoir, the Funisciurus anerythrus squirrel © Mathias D'haen-GabonBiota.org portal

Tamara Giles-Vernick, an anthropologist at the Institut Pasteur, carried out a study to find out about the hunting practices of local populations. Having completed her PhD in the CAR 30 years ago, she was able to demonstrate that hunting practices have changed. "Forty-five years ago, people hunted large game more easily, so rodents were not consumed or even sought after. But with the difficulties in animal breeding and the reduction in populations of large animals, people have become dependent on small animals for animal proteins. We are observing a change in hunting practices," explains Tamara Giles-Vernick. "In areas where large game is declining, rodents seem to be reproducing quickly, leading to a change in the profile of forest animals." Observations show that the capture and consumption of squirrels has been on the rise over the past 30 years.

Tamara's study also shows how local populations have interpreted the arrival of mpox. "It is important to be aware of the way in which people experience illnesses and explain them among themselves. Local populations do not know where mpox comes from but the arrival of such novel diseases is seen as a reflection of a political and economic decline since the 1980s. If an adult contracts mpox, it can also be perceived as being linked to witchcraft, often blamed for bad fortune. So it is crucial to adapt communication at a local level to remove any stigma, make sure that people understand what is happening and encourage them to comply with public health advice," adds Tamara. Even the name of the disease is different from one region to another, highlighting the need for communication tailored to each area.

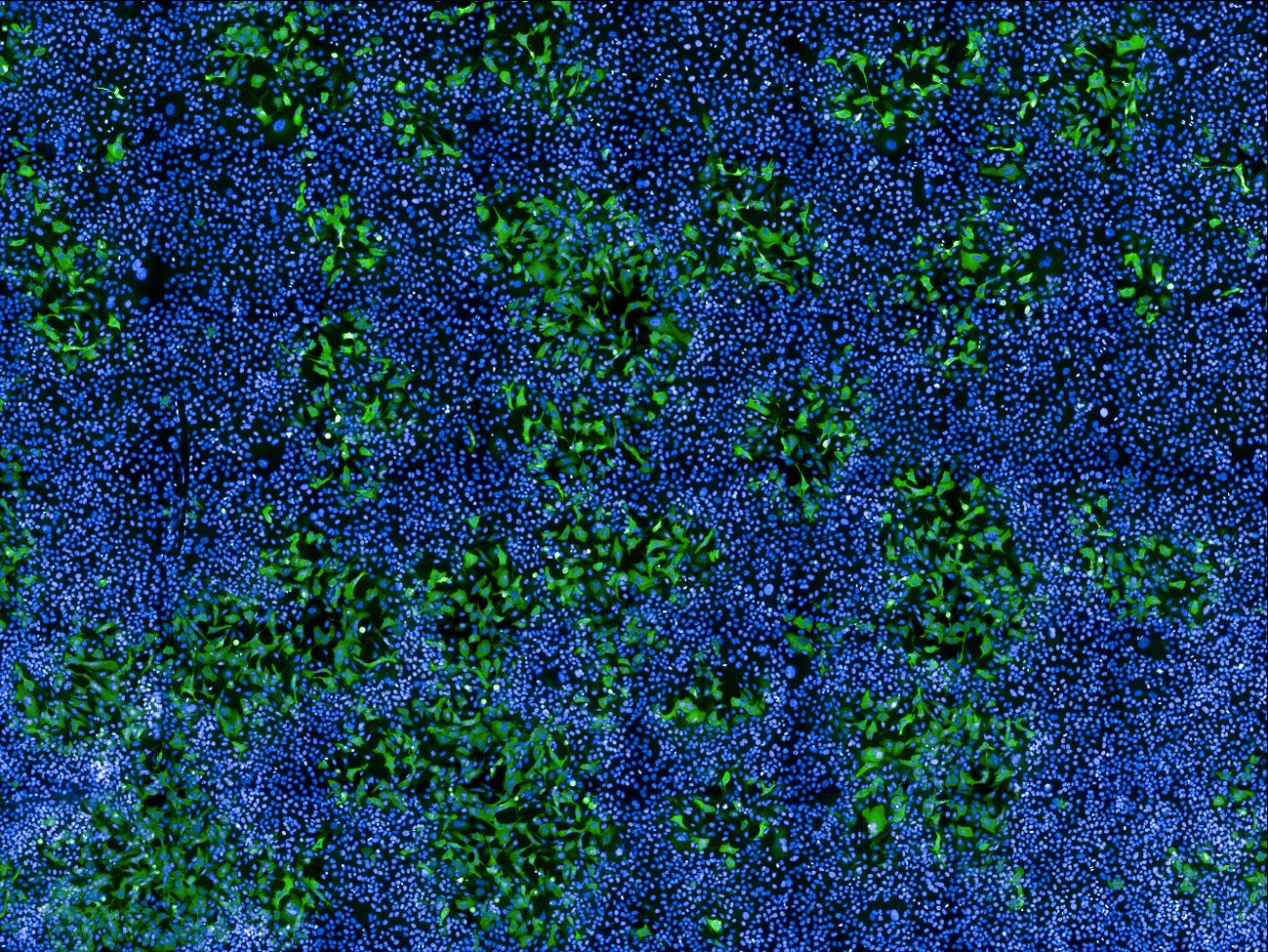

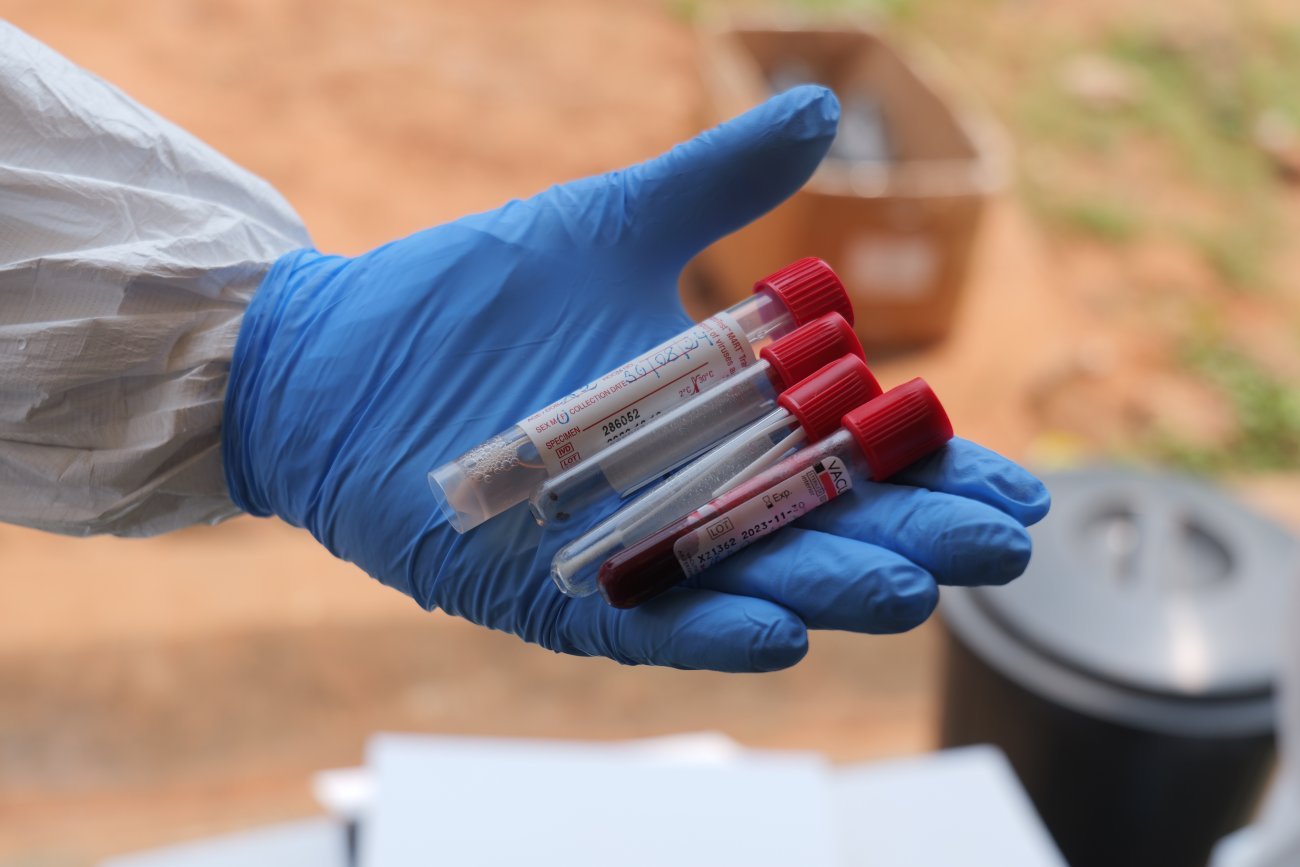

New diagnostic tests confirmed in the laboratory

The introduction in 2022 of rapid dipstick tests confirmed in the laboratory raises hopes for diagnosing the disease in the field. "The tests use a technique whereby secretions from pustules (pus-filled sores) can be collected on dipsticks to confirm or rule out the presence of the virus," explains Emmanuel Nakouné. These tests, currently under development, will be usable in remote regions at the patient's bedside, facilitating crucial early detection to contain viral spread.

Sequencing methods under development

Novel sequencing methods are being developed using techniques suitable for less well equipped laboratories. This technology can be used to monitor the spread of the virus, quickly detect mutations and adapt response strategies. It plays an important role in the general surveillance of the disease, facilitating anticipation and ensuring a more effective response to outbreaks.

Viral sequencing has shown that the strains circulating in the CAR are closely related to the DRC strain, and that the first cases of these strains are likely to have emerged in 1945. They are thought to have separated in the 1960s-70s following population movements at the time, which would explain the difference between the strains in south-west and south-east CAR.

Future strategies to prevent mpox outbreaks

Future strategies include developing integrated surveillance practices and transferring knowledge to local healthcare providers and between different regional and international entities.

The Afripox project, which came to an end in 2024, opened up new avenues for research. One key challenge is the risk that MPXV will continue to circulate in urban African areas among populations at high risk of sexual transmission. The diagnostic tests under development should facilitate epidemiological investigations (serological assays) and treatment for patients (molecular bedside tests). Identification of at-risk populations will also help guide healthcare authorities in leading prevention campaigns and rolling out vaccines that are currently being transported to the region. This targeted strategy went a long way to helping industrialized countries curb the outbreak in 2022.

Scientific publications:

Seasonal Patterns of Mpox Index Cases, Africa, 1970–2021, Emerging Infectious Diseases, May 2024

A time of decline: An eco-anthropological and ethnohistorical investigation of mpox in the Central African Republic, PLOS Global Public Health, March 22, 2024

Identifying the Most Probable Mammal Reservoir Hosts for Monkeypox Virus Based on Ecological Niche Comparisons, Viruses, March 11, 2023

Investigation of a mpox outbreak in Central African Republic, 2021-2022, One Health, March 7, 2023

Development and Characterization of Recombinase-Based Isothermal Amplification Assays (RPA/RAA) for the Rapid Detection of Monkeypox Virus, Viruses, September 23, 2022

Rapid Detection of the Varicella-Zoster Virus Using a Recombinase-Aided Amplification-Lateral Flow System, Diagnostics, November 25, 2022

Nanopore sequencing of a monkeypox virus strain isolated from a pustular lesion in the Central African Republic, Scientific Report, June 24, 2022

National Monkeypox Surveillance, Central African Republic, 2001-2021, Emerging Infectious Diseases, December 2022

Genomic history of human monkey pox infections in the Central African Republic between 2001 and 2018, Scientific Report, June 22, 2021

Tests © Institut Pasteur de Bangui

Tests © Institut Pasteur de Bangui