Researchers from the Institut Pasteur and the CNRS have recently demonstrated that it is possible to destroy the cell wall of a bacterium by simply disrupting the assembly of two proteins. They focused on Helicobacter pylori, a model bacterium for this type of study. Their research has revealed the structure of a protein complex, which is vital for cell wall synthesis. And they have proved that, by blocking the formation of this complex, the bacterium dies. This scenario could be reproduced, as a therapeutic strategy, to destroy the bacterium.

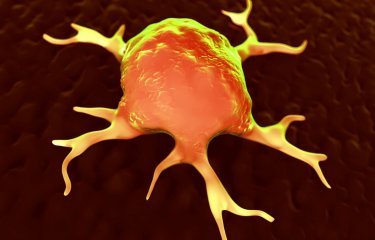

How do bacteria produce their cell walls? When trying to answer this question, teams from the Institut Pasteur and the CNRS looked at Helicobacter pylori, a bacterium known for infecting gastric mucosa (see the report Infection-related cancer) and whose cell envelop is interesting to study. "It is a model bacterium that is easy to track genetically", explains Ivo Gomperts Boneca, Head of the Institut Pasteur's Biology and Genetics of the Bacterial Cell Wall laboratory.

Until now, the scientific community knew that bacterial cell wall synthesis involved an entire protein machinery. "In 2011, we identified a complex made up of two proteins, PBP2 and MreC, whose assembly proved essential to bacterial function1. This protein complex is required for the elongation of the bacterium, which would otherwise be round in shape." The complex is, in fact, called elongasome. Furthermore, the elongated shape that it gives to the bacterium is linked to the bacterium's ability to colonize the stomach lining.

The bacterium loses its elongated shape and dies

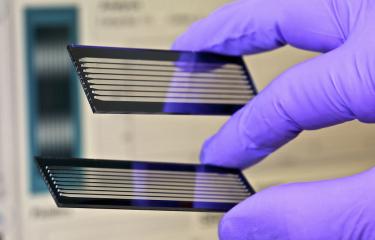

Through research conducted in 2017, "crystallography techniques have enabled us to go a step further, to clearly identify the structure of the PBP2:MreC complex and observe what happens when this pair of proteins malfunctions." Our research showed that if we disrupt the association of the two proteins, not only does Helicobacter pylori fail to elongate but it ends up dying.

"A new strategy for combating bacteria would be to identify the molecules – natural products from plants or fungi – that prevent the assembly of this protein complex." This will be the focus of future research by the team led by Ivo Gomperts Boneca, who points out: "Through our research, we have already identified one molecule that disrupts this assembly. We need to continue testing other molecules."

This project was funded by the CNRS, the Institut Pasteur, the French Foundation for Medical Research, the European Research Council and the French "Investing in the Future" program (LabEx IBEID).

1. Characterization of the elongasome core PBP2 : MreC complex of Helicobacter pylori. Meriem El Ghachi, Pierre-Jean Matteï, Chantal Ecobichon, Alexandre Martins, Sylviane Hoos, Christine Schmitt, Frédéric Colland, Christine Ebel, Marie-Christine Prévost, Frank Gabel, Patrick England, Andréa Dessen and Ivo G. Boneca. Molecular Microbiology, July, 2011.

Source

Molecular architecture of the PBP2–MreC core bacterial cell wall synthesis complex, Nature Communications, October 3, 2017.

Carlos Contreras-Martel1, Alexandre Martins1, Chantal Ecobichon2,3, Daniel Maragno Trindade4, Pierre-Jean Matteï1, Samia Hicham 2,3, Pierre Hardouin1, Meriem El Ghachi2,3, Ivo G. Boneca2,3*, and Andréa Dessen1,4*

1. Grenoble Alps University, CNRS, CEA, Institute of Structural Biology (IBS), Bacterial Pathogenesis Group, F- 38044 Grenoble, France.

2. Institut Pasteur, Biology and Genetics of the Bacterial Cell Wall Group, F-75015 Paris, France.

3. INSERM, Avenir Group, F-75015 Paris, France.

4. Brazilian Biosciences National Laboratory (LNBio), CNPEM, Campinas 13084-971, São Paulo, Brazil.

Infection-related cancer