Scientists from the Institut Pasteur have proved that NK cells ("natural killer" cells in the immune system) migrate to lymphoid follicles, where they control replication of SIV (simian immunodeficiency virus). This new, previously undiscovered function of NK cells was revealed following research into SIV infection in African green monkeys. It raises the prospect of one day being able to control HIV in humans that have stopped treatment, a phenomenon that is currently only seen very rarely in a handful of patients known as post-treatment controllers. This finding also suggests that NK cells in the lymph nodes may play a role during other viral infections – or even in vaccinations.

"We know that HIV replicates in several tissues and that once it is well established, our body is unable to eliminate it," begins Michaela Müller-Trutwin, Head of the HIV, Inflammation and Persistence Unit at the Institut Pasteur. The triple therapy currently used to treat HIV reduces the viral load in the bloodstream to such an extent that it becomes undetectable in hospital tests, even though "it can still be detected in laboratory tests, especially in tissues," explains the scientist. But when treatment is stopped, the viral load in the blood soon returns to its initial level, on average after just two weeks. So we know that the virus persists in reservoirs and waits for an opportunity to strike back.

Surprisingly, some patients are able to control viral replication themselves after stopping treatment (for example the patients in the VISCONTI cohort). "These patients have lower levels of the virus in their reservoirs and have probably developed a stronger immune response," continues Michaela Müller-Trutwin. The big question is whether scientists might one day be able to find a therapy that reduces viral reservoirs and strengthens the immune response so that patients can go into remission.

A new function of "natural killer" cells (NK cells)

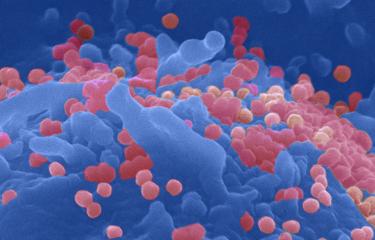

Michaela Müller-Trutwin and her team therefore decided to focus their research on the lymph nodes, HIV's primary tissue reservoir. "Lymph nodes can be divided into two areas, one containing CD8 T lymphocytes and the other B lymphocytes (follicles). The virus hides and replicates in CD4 T lymphocytes in follicles." The team recently proved that NK cells ("natural killer" cells in the immune system) migrate to lymphoid follicles, where they control replication of SIV (simian immunodeficiency virus) in African green monkeys. This is a new, previously undiscovered function of NK cells.

"We decided to study African green monkeys because they have been infected for at least 100,000 years by SIV, a virus similar to HIV in humans," explains Michaela Müller-Trutwin. "However, they have managed to strike a balance: half of them are carriers of SIV with very high viral load levels in the blood, but they do not become ill – their immune system resists the virus." How can these monkeys with a high level of the virus in their blood manage to protect their lymph nodes and stop them becoming a reservoir for SIV? NK cells play a vital role in antiviral immunity, but we still know relatively little about their function in secondary lymphoid organs. "For many years it was even thought that NK cells did not have a specific role to play in the lymph nodes. But we observed that in African green monkeys, NK cells are strongly activated in the lymph nodes following SIV infection. So we tried to find out why."

What do NK cells do in the lymph nodes?

And the scientists' observations were surprising. Immediately after SIV infection, these NK cells express a cell surface receptor (known as CXCR5) which attracts them to follicles in the lymph nodes. "The NK cells therefore move to a place where they are not supposed to be," continues the scientist. And what do they do in the lymph nodes? "They control viral replication." The team demonstrated that SIV infection in green monkeys triggers production of the IL-15 cytokine in follicles. IL-15 is known to be involved in the survival and cytotoxic function of NK cells. Removing the NK cells resulted in mass replication of the virus in the lymph nodes, especially in the follicles. This proves that NK cells play an important role in controlling viral replication in the lymph nodes of monkeys that are carriers of SIV but do not develop the disease.

"We have demonstrated a new function of NK cells: their ability to migrate to lymphoid follicles and differentiate there to control viral replication in an area known to be the primary anatomical reservoir for HIV," concludes Michaela Müller-Trutwin.

A new hope to fight infectious diseases

This raises several questions for the scientific community. Are there correlations between patients who are able to control HIV after treatment and the role of NK cells in their lymph nodes? And do NK cells in the lymph nodes play a part in other viral infections? The unexpected discovery of NK cells in the follicles also raises the question of their interaction with other cells in this area, especially B lymphocytes, and the impact on antibody responses to vaccination. This finding opens up a whole new avenue of research that might help improve our understanding of the biology of the immune system.

This research was funded by the VRI (ANR-10-LABX-77), the ANRS and the Institut Pasteur.

Source

Natural killer cells migrate into and control simian immunodeficiency virus replication in lymph node follicles in African green monkeys, Nature Medicine, October 16, 2017

Nicolas Huot1,2, Beatrice Jacquelin1, Thalia Garcia-Tellez1, Philippe Rascle1–3, Mickaël J Ploquin1, Yoann Madec4, R Keith Reeves5, Nathalie Derreudre-Bosquet6 & Michaela Müller-Trutwin1,2

1. Unit on HIV, Inflammation and Persistence, Institut Pasteur, Paris, France.

2. Vaccine Research Institute, Créteil, France.

3. Université Paris Diderot, Sorbonne Paris Cité, Paris, France.

4. Epidemiology Unit, Institut Pasteur, Paris, France.

5. Center for Virology and Vaccine Research, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

6. Commissariat à l'Energie Atomique et aux Énergies Alternatives (CEA), Université Paris Sud 11, INSERM U1184, Immunology of Viral Infections and Autoimmune Diseases (IMVA), Institut de Biologie François Jacob (IBJF), Infectious Disease Models and Innovative Therapies (IDMIT) Department, Fontenay-aux-Roses, France.

For more information, please visit