Lyme disease is caused by bacteria transmitted by the bite of an infected tick of the Ixodes genus. Researchers from the Institut Pasteur have investigated tick infection when Siberian chipmunks are present, as these rodents are thought to be a reservoir for the bacteria. This pet, which was popular in the 1970s, was introduced to some forests where it now thrives, like in Sénart Forest, south-east of Paris. The research has confirmed that these chipmunks were responsible for an increase in tick infection. But there are fewer ticks where the chipmunks are found. Why is this?

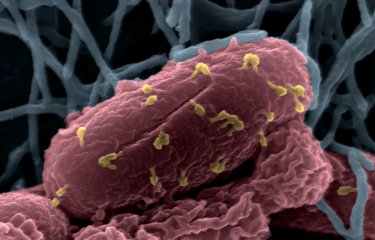

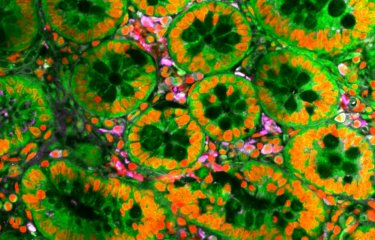

Lyme borreliosis (LB) – which is also known as Lyme disease and is linked to pathogenic bacteria of the Borrelia burgdorferi complex in a broad sense – is the most widespread vector-borne zoonosis in the northern hemisphere. In France, it is spread by the Ixodes ricinus tick, an arthropod that lives on a large number of hosts, including some Borrelia reservoirs (small mammals, birds, reptiles). Humans are only accidental hosts. Among the small mammal reservoirs is the Siberian chipmunk (Tamias sibiricus), a rodent that became a pet in the 1970s and was often abandoned by its owners in nearby forests.

Researchers from the Institut Pasteur therefore assessed the development of tick infection by the different species of Borrelia bacteria. By comparing the findings obtained over three years1 (2008, 2009 and 2011), they ascertained the consequences of the proliferation of this non-native rodent species on the risk of transmission of the disease.

"We investigated the eco-epidemiological factors of Lyme disease in three forests in the Greater Paris region (Sénart, Notre-Dame and Rambouillet), explains Valérie Choumet, a scientist in the Environment and Infectious Risks Unit. Sénart Forest is an interesting site because, following their introduction there 40 years ago, the chipmunks have gradually taken over the forest, but especially the western side (the eastern side is still relatively free of the rodents)." So, the scientists studied the forest as a whole and looked to see if there were any differences in tick infection rates or nymph density: "we determined their numbers because they are small and not easy to spot and, as a consequence, are often responsible for transmitting Lyme disease to humans."

The findings were compared with those obtained for ticks collected in 2009 in two other Greater Paris region peri-urban forests (Rambouillet and Notre-Dame), which have not been colonized by these rodents.

Chipmunks do indeed infect the nymphs

"There is certainly a higher infection rate among nymphs when chipmunks are present", observes Valérie Choumet. But, luckily, this part of the forest has fewer fruit trees, like sweet chestnut trees, and is less likely to appeal to animals that the ticks latch onto for their blood meals. "Nymphs are therefore fewer in number there."

On the other side of the forest, which is separated from the western part by a highway, there are very few, if any, chipmunks. They are only just starting to colonize this area. "This part, however, abounds in sweet chestnut trees and other fruit trees. It could therefore attract deer or wild boar on which ticks like to feed and nymphs would be higher in density there.

No premature conclusions regarding the risk in Sénart Forest

The study provides useful information about the spatio-temporal distribution and infection of ticks collected in peri-urban forests, which are popular recreation sites.

Findings suggest that the chipmunk, this newly-introduced species, may be involved in the rate of tick infection with Borrelia. If its population grows, it could colonize the part of the forest where the nymphs are greater in number and play a major role in spreading the pathogen. "But we must remain cautious because the density of infected nymphs can vary according to the year". There are so many factors that can affect animal reservoir populations. In colder years, for example, there are fewer rodents and they can suffer from the lack of fruit.

Finally, regarding Sénart Forest, "there is not one part of the forest that is more dangerous than the other today", points out Valérie Choumet. And the risk is no greater in this forest than any other one. Sénart was chosen because it has been a major study site for the last few years and a great deal of data has been collected that can be analyzed. The risk is present in any forest. In addition, "we can stress that the risk identified in the peri-urban forests of Greater Paris is well below the one identified in Alsace in 2003-2004, when the rate of tick infestation with Borrelia and the density of infected nymphs were significantly higher." Furthermore, as the risk varies according to the year, "more recent data from our colleagues in Alsace shows lower rates nowadays." The disease continues to be monitored at the National Reference Center for Borrelia, now located in Strasbourg2.

1. Research carried out with the National Reference Center for Borrelia, when it was housed at the Institut Pasteur from 2002 to 2011.

2. Current National Reference Center for Borrelia.

Lyme, a complex disease

Source

Infection of Ixodes ricinus by Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in peri-urban forests of France, PLoS One, August 28, 2017.

Axelle Marchant1*, Alain Le Coupanec1*, Claire Joly1*, Emeline Perthame2, Natacha Sertour1, Martine Garnier1, Vincent Godard3, Elisabeth Ferquel1,§*, Valerie Choumet1,4,$*

1 Centre National de Référence des Borrelia, Institut Pasteur, 28 rue du Dr Roux, 75724 Paris cedex 15, France

2 Institut Pasteur – Bioinformatics and Biostatistics Hub – C3BI, USR 3756 IP CNRS – Bioinformatique et Biostatistique, 28 rue du Dr Roux, 75724 Paris cedex 15, France

3 CNRS-UMR7533/LADYSS, Université de Paris 8 - Saint-Denis, France

4 Unité Environnement et Risques Infectieux, Institut Pasteur, 25 rue du Docteur Roux, 75724 Paris cedex 15, France

For more information, please visit