A team from the Institut Pasteur used a combination of molecular biology, genomics and artificial chromosomes, aided by artificial intelligence (AI), to explore how a DNA molecule behaves when it enters the nucleus of a eukaryotic cell. Their research, published recently in the prestigious journal Science, reveals that the DNA's fate differs considerably depending on its sequence composition.

Transfers of DNA molecules from one species to another occur relatively frequently on an evolutionary scale, but DNA transfer can also occur in other contexts. For example, when microbes, viruses or bacteria infect an organism, their DNA can enter host cells, invade the nucleus and even become integrated into the genome. This can result in significant changes in both the host cell and the exogenous microbial DNA.

Ancestral DNA reactions still largely unexplored

We know that DNA sequence composition1, chromatin2 structure, and nucleotide motifs3 vary not only from one species to another but also within the same genome. This reflects billions of years of evolution. So when exogenous DNA invades or enters the nucleus of a host cell, it encounters regulatory mechanisms and rules under which it has not necessarily evolved. The way in which host cells process these DNA molecules as they enter the nucleus and sometimes end up adopting these exogenous sequences remains largely unexplored.

1. DNA sequence: the organization of the four bases A-T and G-C (the chemical compounds that make up DNA) in a DNA molecule.2. Chromatin: a substance formed of DNA and proteins that constitutes the genome of eukaryotic cells. It is also known as the nucleosome.

3. Nucleotide motifs: patterns that form the basis of DNA and determine the order of the nucleotides A, T, G and C in a molecule.

Studying bacterial DNA in yeast, a eukaryotic organism

How does a eukaryotic host respond when foreign DNA enters its nucleus? And what levels of genome regulation are involved in regulating this foreign DNA? The topic was explored at the Institut Pasteur by around 20 scientists from the Spatial Regulation of Genomes unit.

Unit head Romain Koszul launched the project following a seminar given at the Institut Pasteur in 2016 by Carole Lartigue, a scientist at INRAE in Bordeaux. The scientist presented the research she had undertaken at the J. Craig Venter Institute aimed at using baker's yeast as an intermediate host for the synthesis and transfer of bacterial genomes of the genus Mycoplasma. Yeast, a single-cell eukaryotic microorganism that has long been used as a model by geneticists, is a good tool for hosting and manipulating exogenous DNA. The Institut Pasteur project initially set out to explore a simple question:

"At the start, our approach was purely exploratory and driven by curiosity. We wanted to know how the yeast genome is organized in the nucleus when we make it coexist with a whole bacterial genome. But this gave rise to increasing quantities of data and sparked many more questions – it was like unraveling a ball of wool!"

Does bacterial DNA remain silent or become active once inside the host cell?

The scientists investigated three main characteristics to determine how exogenous DNA adapts to its host.

- First, the composition of the chromatin formed by the DNA: is it different from the host chromatin?

- Second, transcription: is the foreign DNA actively transcribed into RNA, or does it remain inactive – transcriptionally "silent"?

- Third, its 3D organization in the nuclear space: is this long strip of genetic code unfolded or folded on itself?

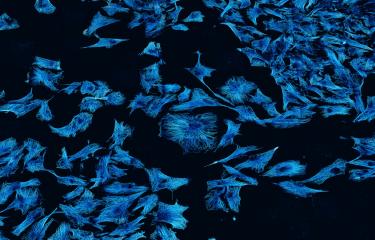

By comparing the results of functional experiments and bioinformatic analysis, the scientists demonstrated that the transcription of exogenous DNA depends on its composition, in other words the proportion of AT and GC base pairs. Moreover, if the exogenous DNA is not transcribed, it forms a nuclear compartment in which it is segregated from the actively transcribed yeast chromosomes, thereby leading to compartmentalization of the genome.

The team then wanted to identify the extent to which the genomic sequence of the exogenous DNA, which influences this behavior, can be used to predict how the DNA will adapt to its host cell. This is where AI came in. A deep learning4 application was designed with the collaboration of the Repeated DNA, Chromatin, Evolution team led by Julien Mozziconacci at the French National Museum of Natural History (MNHN), with whom Romain Koszul has been working for more than a decade.

4. Deep learning : a method that uses algorithms with the potential for learning. Deep learning is the main reason for the renewed increase in artificial intelligence over the past few years.Read the article to find out more: Artificial intelligence: deep learning is blazing ahead

DNA fate determined by its composition

Jacques Serizay, a postdoctoral fellow in bioinformatics and co-first author of the study, coordinated the integration of experimental multi-omics data and ensured that the AI results obtained by the museum team were in line with these observations: "We used an AI developed by the museum that is capable of simulating a large number of different scenarios depending on the characteristics of the yeast and the foreign DNA. We mainly varied the DNA sequence and the number of GC base pairs."

More than 10,000 hypotheses were tested in silico, and the results confirmed an important experimental conclusion: the fate of exogenous DNA is directly determined by its composition. If the DNA has a similar number of GC pairs to the yeast genome, it becomes very active. It intermingles with the chromosomes it encounters and adapts easily. But if it has a low GC rate, the DNA is silent and inactive, forming a separate globular compartment within the nucleus.

This study and the methodology used could have several applications. "Other AI systems may be developed to predict the behavior of invasive sequences in very different contexts," explains Romain Koszul. "We are already using this system regularly in the lab to test theories in other projects!"

Source

Sequence-dependent activity and compartmentalization of foreign DNA in a eukaryotic nucleus, Science, February 6, 2025.