AIDS: progress and fresh hope

Having claimed the lives of close to 40 million people (source: OMS 2017) since HIV was discovered in 1983, AIDS is indeed a global health catastrophe. Significant progress has nevertheless been made over the last few years, particularly in developed countries, with longer life expectancy for patients on triple therapy. But this treatment does not eliminate the virus and must be taken for life. Research is therefore continuing to try and find curative treatments and/or a protective vaccine. Here is an overview of the work carried out at the Institut Pasteur.

Roughly 10 extra years of life. In Europe and North America, this is the life expectancy that people infected with the AIDS virus (HIV) have gained since the introduction of triple therapy in 1996, according to a study conducted on 88,504 patients and published in The Lancet HIV in May 2017. AIDS however remains the "greatest health catastrophe" the world has ever known, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), which has recorded over one million deaths from AIDS every year since the early 1980s (i.e. close to 40 million to date). The number of people carrying HIV is currently increasing, mainly because the number of new infections in adults has not fallen for 10 years and people who have access to treatment, i.e. approximately half of HIV-positive patients worldwide, are living longer.

Figures do however show considerable progress in care – the annual number of deaths is falling (42% drop since 2004*) and access to antiretroviral treatment is improving (84% rise since 2010*). But huge disparities remain in the world. Only 1.8 million out of the 6.5 million people living with HIV in Western and Central Africa were receiving antiretroviral treatment in late 2015. That means 28% of people are treated in the region, which contrasts the 54% coverage obtained the same year in Eastern and Southern Africa*.

*Source: UNAIDS

Will the epidemic be controlled any time soon?

The international response has stopped the spread of the virus. UNAIDS* has set a target called "90-90-90" to put an end to the epidemic by 2020. Rather than simply focus on the number of people receiving treatment, the new "90-90-90" target recognizes the need to look at the quality and results of antiretroviral therapy. The aim is that:

- 90% of all people living with HIV will know their HIV status.

- 90% of all people with diagnosed HIV infection will receive sustained antiretroviral therapy.

- 90% of all people receiving antiretroviral therapy will have viral suppression.

*United Nations (UN) Program designed to coordinate the initiatives of the various UN specialized agencies to fight the HIV/AIDS pandemic.

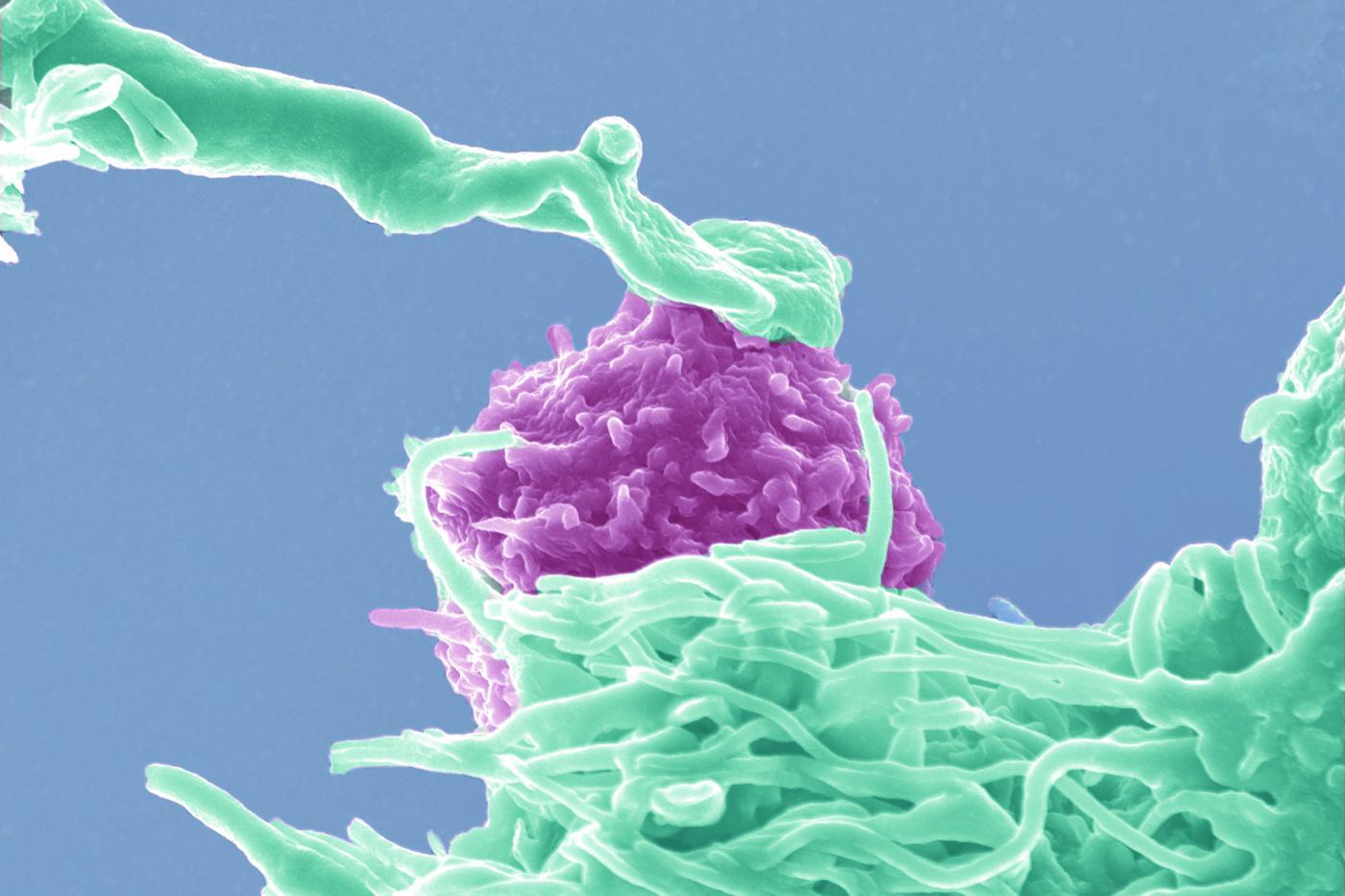

HIV attacks the immune system

HIV is the human immunodeficiency virus. It is an RNA virus with high adaptability. It infects the immune system cells (CD4+ T lymphocytes) and hijacks their cellular machinery to replicate and produce new viral particles. These lymphocytes are gradually impaired. The body can then no longer defend itself against infection and disease. The term AIDS (Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome) refers to the advanced stage of the disease, when the immune system becomes incapable of fighting bacterial, parasitic or fungal infections – known as "opportunistic" infections because they take advantage of weak immune systems to take hold – or the possible onset of cancer. Today, in treated individuals with a well-controlled viral load, the risk of developing AIDS is extremely low, but there is a risk of developing other diseases, such as cancer or cardiovascular diseases, if the infection is not treated early enough.

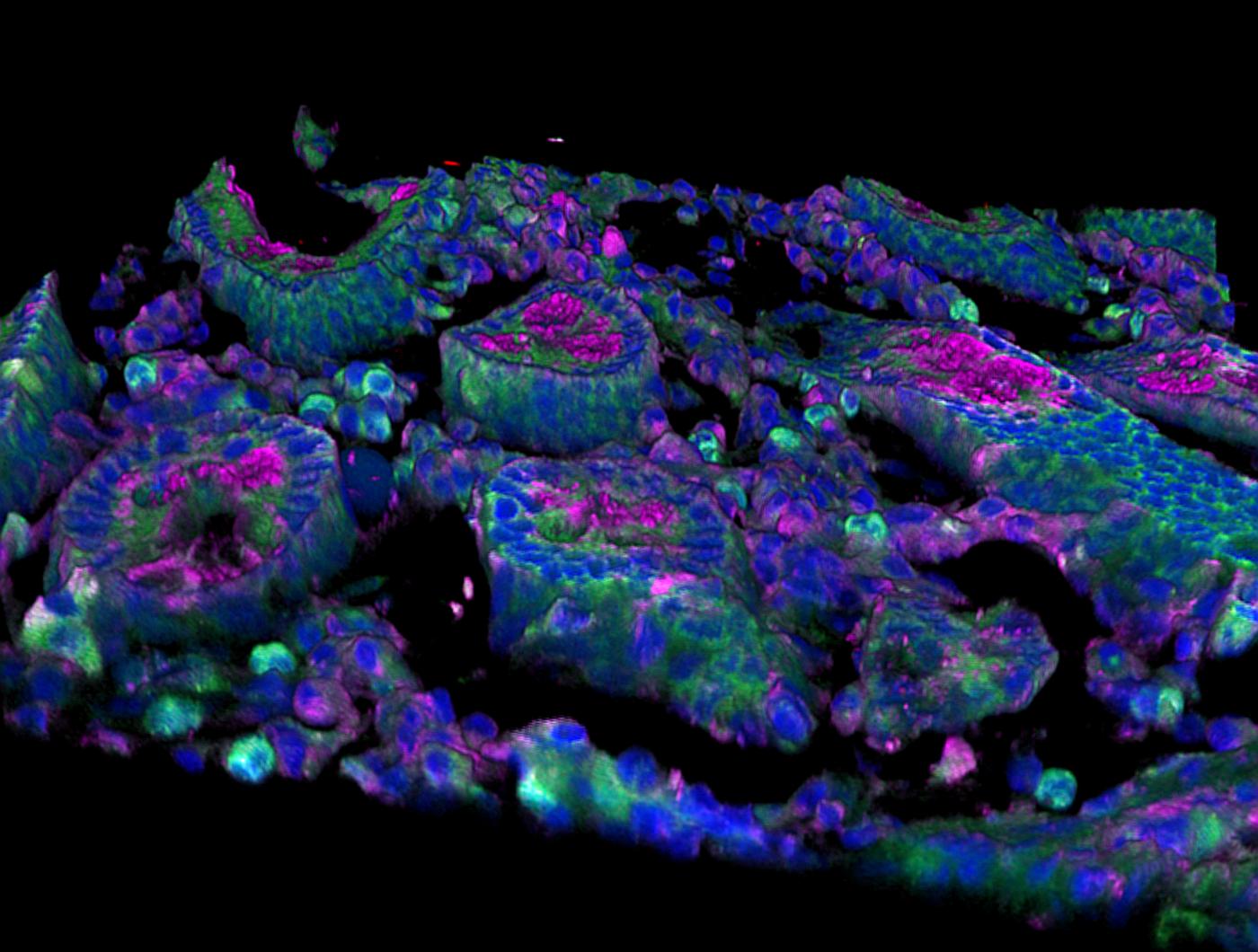

Innate immunity, central to HIV replication

The role of innate immunity constitutes a very active HIV research field. At the Institut Pasteur, several laboratories are working on the role of dendritic cells, macrophages and natural killer cells in inducing specific immune responses. We know that HIV multiplies in organs, like lymph nodes, particularly their follicles, but these follicles are major antibody production sites. The high replication rate of the virus in these follicles could therefore disrupt the induction of effective antibody responses. The HIV, Inflammation and Persistence Unit at the Institut Pasteur*, directed by Michaela Müller-Trutwin, is analyzing innate immune responses within the follicles, thanks to imaging and 3D visualization technology. These studies shed new light on possibilities for controlling viral replication.

*In partnership with the Infectious Disease Models and Innovative Therapies Center (IDMIT) at the CEA, and with the support of the French Vaccine Research Institute (VRI) in Créteil.

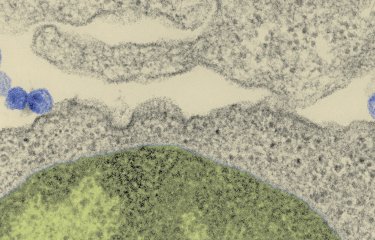

Intestinal cells producing a cytokine that protects against AIDS the African monkey Chlorocebus (sometimes called "green monkey"), infected with the SIV immunodeficiency virus (SIV). © Institut Pasteur/Nicolas Huot 2017

There are several strains of HIV. HIV-1, which was discovered at the Institut Pasteur, is behind almost all contaminations in humans. It originates from the great African apes (chimpanzees and gorillas), which carry the simian immunodeficiency virus, or SIV. "Furthermore, in the late 1980s, Martine Peeters – a virologist from the French Research Institute for Development (IRD) and the University of Montpellier – was the first person to observe this virus in monkeys in Gabon", recalls Françoise Barré-Sinoussi, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2008, with Luc Montagnier, for discovering HIV-1. A few years later, the geographical origin of HIV-1 was pinpointed thanks to an SIV strain particularly close to HIV-1 which was isolated at the Pasteur Center in Cameroon. This reminder shows just how much research has always involved multiple stakeholders, particularly for AIDS.

.

We discovered HIV-1 after our hospital colleagues questioned us about the causative agent of AIDS. Nothing would have been possible without multidisciplinary research and close cooperation with clinicians and patient representatives.

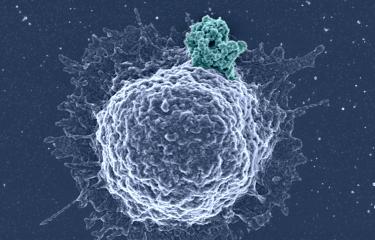

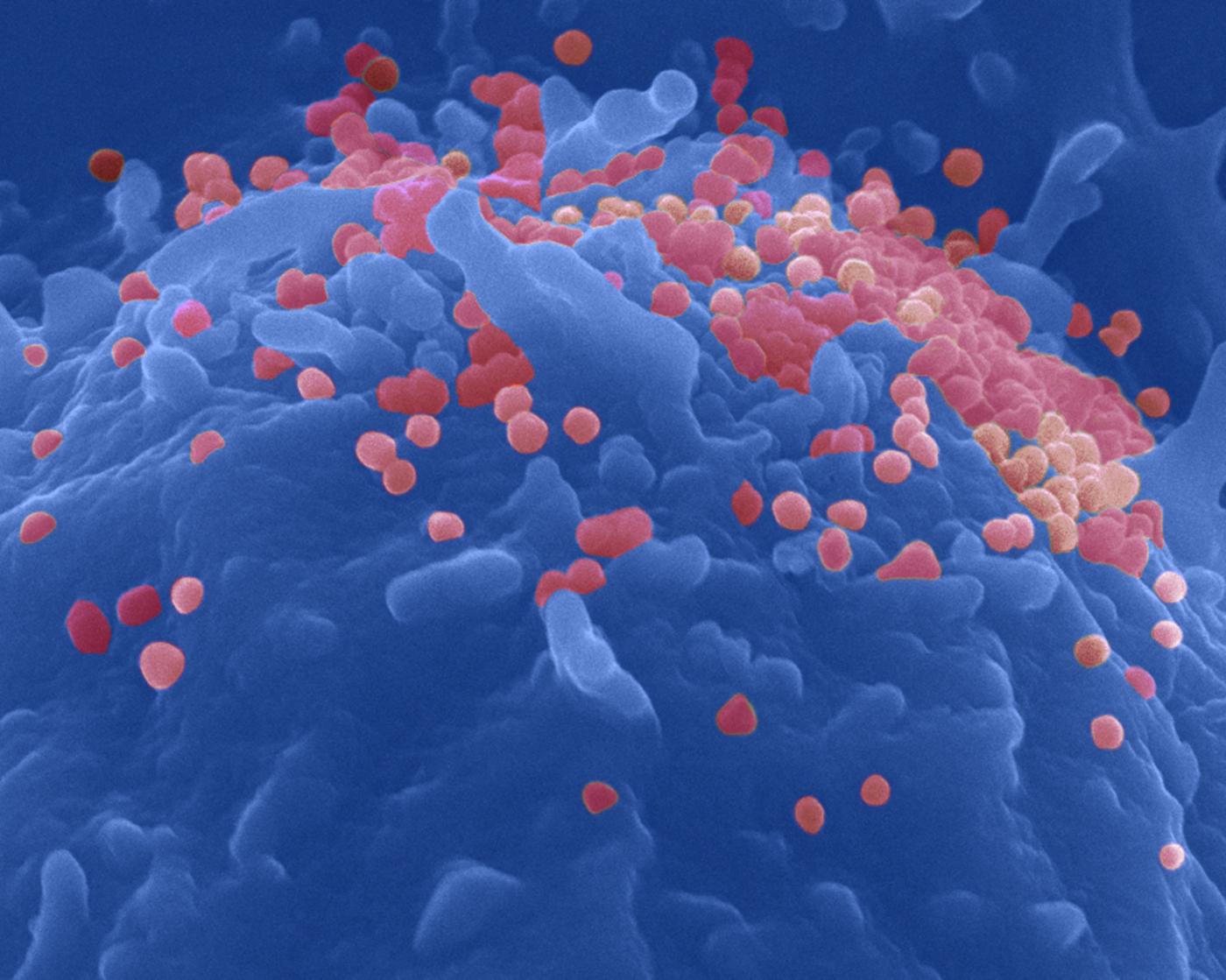

Citation of Françoise Barré-Sinoussi, 2008 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine for the co-discovery of the HIV virus - Photo: HIV-1 virus (causative agent of AIDS) on the surface of a lymphocyte. Virus isolated and identified at the Institut Pasteur in 1983. Colored image. © Institut Pasteur / Photographer - Author: Charles Dauguet.

Working together for the benefit of patients

In France, scientific and health authorities such as Inserm, the Paris Public Hospital Network (AP-HP), CNRS, CEA, Institut Pasteur, IRD and universities all make a significant contribution to AIDS research. Since 1992, the French National Agency for AIDS Research has sought to provide real solutions for people living with HIV, in partnership with the above-mentioned bodies and a network of researchers, veterinarians and clinicians to conduct pre-clinical and therapeutic trials. The hospital sector (AP-HP, regional hospitals, etc.) has always been a key partner in AIDS research.

At international level, cooperation is also growing amongst scientific bodies and health care facilities, which is essential for progress in research and has the backing of various institutions (European Commission, WHO, UNAIDS, etc.).

© Institut Pasteur - Musée Pasteur / © Institut Pasteur

Current treatment

As there was no effective treatment in the early years of the AIDS epidemic, patients progressed to the advanced stage of the disease and died.

Today, standard therapy combines several (often three) antiretroviral drugs (triple therapy). Viral replication is then brought under control and HIV is no longer detected in the blood. To a greater or lesser extent, the immune system regains its efficacy against other pathogens. However, the persistence of the virus induces chronic inflammation, which is linked to a risk of developing diseases such as diabetes, cancer and cardiovascular problems.

And, to be fully effective, the treatment needs to be taken early. The virus is never completely eliminated from the body either as if therapy is stopped, the virus returns to the blood at the same levels as before treatment. This is because the latent virus remains in cells known as "reservoirs", which appear very early on, within three days of infection.

Research into future AIDS treatment is closely linked to vaccine research. The two must be considered together.

What are the current avenues of research for new HIV treatment?

Firstly, it must be remembered that current therapies do not completely eliminate the virus. At the Institut Pasteur, HIV research focuses on everything from molecular and cell level to humans, patient cohorts and populations of infected individuals, to try and find a treatment that will one day be able to cure patients or at least induce lasting remission. An original line of research involves understanding the mechanisms that control the infection in patients in the VISCONTI study. These patients, who received treatment very early on, have very low viral reservoir rates and controlled viral replication several years after stopping their antiretroviral therapy.

Why is this line of research particularly interesting?

If we manage to induce permanent control of the infection when treatment is stopped, like the control seen in VISCONTI patients, we could then talk of lasting remission. A European consortium (ANRS-RHIVIERA), coordinated by Asier Saez-Cirion* at the Institut Pasteur, has been formed based on this promising avenue. Its aim is to shed more light on HIV persistence and control mechanisms in patients. Then, based on this knowledge, to decide which strategies could be put forward to induce this lasting remission (see section below).

The vaccine route seems more complicated. What is stopping its development?

HIV attacks the immunity cells and prevents effective responses from developing. HIV also varies a great deal. It evades antibodies and the immune response. But the challenge of developing a vaccine seems greater however and not only relevant to AIDS. The scientific community is not yet familiar with all the immunological mechanisms that need to be induced to confer protection. Fundamental research in immunology, carried out at the Institut Pasteur and at many laboratories across the world, must therefore continue to enable vaccines to be developed one day. And not just for AIDS but for malaria, Ebola, Zika… and why not cancer too!

* Coordinated by Asier Saez-Cirion in the HIV, Inflammation and Persistence Unit (directed by Michaela Müller-Trutwin) and with the involvement of several Institut Pasteur teams.

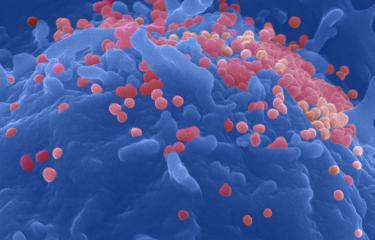

Interaction between a T4 lymphocyte (pink) infected with HIV and a dendritic cell (blue). © Institut Pasteur / Stéphanie Guadagnini and Marie-Christine Prévost, Ultrastructural Microscopy Platform - Nathalie Sol-Foulon and Olivier Schwartz, Virus and Immunity Unit. Colorization Jean-Marc Panaud

From viral persistence to remission

Generally, if a patient stops antiretroviral therapy, the virus starts replicating again and treatment must be immediately reinstated to avoid progression to AIDS. In patients receiving therapy, this can be explained by HIV persistence in the reservoir cells containing the virus in latent state. It is out of range of the antiretroviral drugs, as they intervene at the viral replication stage. However, some patients with favorable genetic factors are able to control the virus naturally. Institut Pasteur teams (Lisa Chakrabarti and Asier Saez-Cirion) are studying these rare HIV controllers to try and understand their control mechanisms and induce them in other patients. The VISCONTI* study has shown that treatment initiated very early on after infection can facilitate viral control in 5-10% of patients after therapy stops (see the "AIDS: 14 adult patients manage to control their HIV infection more than seven years after stopping treatment" press release"). "Remission therefore seems achievable today, explains Asier Saez-Cirion from the HIV, Inflammation and Persistence Unit, directed by Michaela Müller-Trutwin. Patients in remission are still infected with HIV but early treatment seems to have limited the number of infected cells and preserved effective immune control mechanisms. Further fundamental, technological, translational and clinical research is however needed before such prolonged remission of HIV infection can one day become effective. This group of researchers therefore founded the ANRS-RHIVIERA (Remission of HIV Infection Era) consortium with the ANRS in 2014. Pre-clinical and clinical trials have now begun to test new strategies.

*ANRS EP47 VISCONTI (Viro-Immunological Sustained Control after Treatment Interruption) study, funded by the ANRS. CNRS, Inserm, Institut Pasteur; Paris-Sud Faculty of Medicine, Paris Descartes University, Pierre and Marie Curie University (UPMC); Orléans-La Source Hospitals, Kremlin-Bicêtre Hospital, La Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital, Necker Children's Hospital.

Fabrice Hyber. Attempt to describe the development of the marker CD32A, 2017. © Organoid Production/Institut Pasteur

Finally, to give another example of research into HIV persistence, French researchers* identified a marker to differentiate between "dormant" cells (infected with HIV) and healthy cells in March 2017. This study comes under the ANRS "HIV Reservoirs" strategic program. The discovery should enable these reservoir cells to be isolated and analyzed. By silently hosting the virus, these cells are responsible for its persistence, even in patients on antiretroviral therapy whose viral load cannot be detected. It paves the way for new therapeutic strategies by targeting infected cells.

*CNRS, University of Montpellier, Inserm, Institut Pasteur, Henri Mondor Hospital (AP-HP) in Créteil, Gui de Chauliac Hospital (Montpellier University Hospital), VRI.

First case of prolonged remission in an HIV-positive child

In July 2015, a young woman aged 18 and a half at the time and who was born HIV-positive following mother-to-child transmission (either during pregnancy or birth) found herself in virological remission, despite not having taken any antiretroviral therapy for 12 years. Monitored in the French ANRS pediatric cohort, this young woman appears to have benefited from treatment administered soon after birth and continued for roughly six years before it was stopped. Her case suggests that prolonged remission after early treatment can be achieved in children infected with HIV since birth, as has already been demonstrated in adults in the ANRS VISCONTI study.

Antibodies capable of eliminating infected cells

There have been other surprises in store for scientists studying responses to HIV. In 2016, researchers from the Institut Pasteur, CNRS and the Vaccine Research Institute (ANRS/Inserm) LabEx demonstrated that some effective antibodies (broadly neutralizing antibodies or bNAbs) can recognize infected cells and trigger their destruction by the immune system. This discovery made by teams under Olivier Schwartz (Virus and Immunity Unit) and Hugo Mouquet (Humoral Response to Pathogens group), sheds new light on the mechanism of action of these specific antibodies, which are currently undergoing clinical trials. It is also important to understand how these rare antibodies develop (see the "AIDS" press kit). This is something that Hugo Mouquet's group is studying by characterizing memory B cell and antibody responses to HIV-1 in these patients.

AIDS: many other lines of research at the Institut Pasteur

At the Institut Pasteur, HIV research focuses on everything from molecular and cell level to humans, patient cohorts and infected individuals. This transversal and interdisciplinary research, carried out in partnership with many hospitals and national and international organizations, starting with the ANRS, brings together a dozen teams from the departments of Virology, Immunology and Infection and Epidemiology on the Institut Pasteur Paris campus, as well as the Medical Center for the clinical research aspect. This research aims to help find a vaccine and cure for HIV in the context of a pandemic that, although waning, has yet to be tamed. HIV research remains a key priority for the Institut Pasteur and its International Network (information about research carried out in Cameroon, Cambodia, Vietnam, Côte d’Ivoire and the Central African Republic is available in the press kit).

AIDS research at the Institut Pasteur