Listeriosis is a severe foodborne infection that can cause septicemia, central nervous system infection or infection in fetuses and newborn infants. The pathogen responsible for listeriosis, Listeria monocytogenes, is capable of contaminating food and food processing environments. Scientists from the Institut Pasteur, Inserm and the Université de Paris recently revealed that the virulence of Listeria bacteria differs depending on the type of food involved. Dairy products are contaminated with the most virulent bacteria. This important discovery sheds new light on the virulence of Listeria and paves the way for more effective measures to control food contamination and prevent listeriosis.

Listeria monocytogenes is a foodborne bacterium that is pathogenic in humans and animals. It causes listeriosis, an extremely severe infection (see our fact sheet). It was long believed that the different Listeria strains all had the same level of virulence, but the Institut Pasteur/Inserm Biology of Infection Unit (U1117) and the National Reference Center for Listeria (hosted at the Institut Pasteur) previously demonstrated the extreme genetic and phenotypic diversity of Listeria and the existence of hypervirulent and hypovirulent subpopulations (or clones) (see our press release).

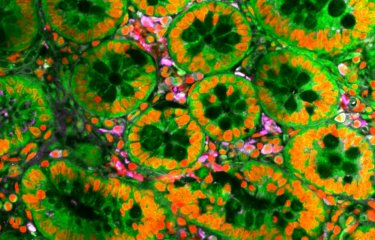

In a new study published in Nature Communications, the scientists reveal that the hypervirulent clones, especially CC1, are associated with dairy products, while the hypovirulent clones, mainly CC9 and CC121, are over-represented in meat and fish products. "Hypervirulent clones colonize the gut lumen and gut tissue more effectively than hypovirulent clones, suggesting that they are better adapted to the host," explains Pr Marc Lecuit, of the Biology of Infection Unit at the Institut Pasteur, of the Université de Paris and of the Necker Enfants Malades University Hospital's Infectious and Tropical Diseases Department. But hypovirulent clones have higher numbers of stress resistance genes that are resistant to a disinfectant widely used in the food industry; these clones are more capable of surviving and forming bacterial populations that adhere to surfaces with low concentrations of this disinfectant, suggesting that they are better adapted to the food production environment.

These findings will help characterize the ecological niches in which Listeria develops virulence and environmental survival capabilities. They also have major public health implications, since they can improve our understanding of how Listeria circulates between different environments. "These results will give us a better idea of how food becomes contaminated so that we can reduce Listeria contamination. They will also help us improve food consumption guidelines for at-risk populations," concludes Marc Lecuit.

Source

Hypervirulent Listeria monocytogenes clones’ adaption to mammalian gut accounts for their association with dairy products, Nature Communications, June 6th, 2019

Mylène M. Maury1,2,3, Hélène Bracq-Dieye1,2, Lei Huang1,4, Guillaume Vales1,2, Morgane Lavina1, Pierre Thouvenot1,2, Olivier Disson1, Alexandre Leclercq1,2, Sylvain Brisse3, Marc Lecuit1,2,5

1 Biology of Infection Unit, Institut Pasteur, Inserm U1117, Paris, France

2 National Reference Centre and WHO Collaborating Centre for Listeria, Institut Pasteur, Paris, France

3 Microbial Evolutionary Genomics Unit, CNRS, UMR 3525, Institut Pasteur, Paris, France

4 Université Paris Diderot, Université de Paris, Paris, France

5 Université de Paris, Institut Imagine, Necker-Enfants Malades, University Hospital, Division of Infectious Diseases and Tropical Medicine, APHP, Paris, France