What are the causes?

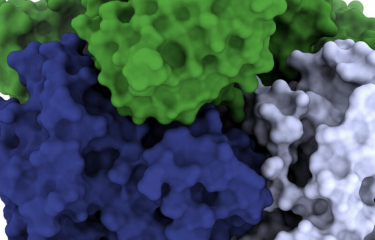

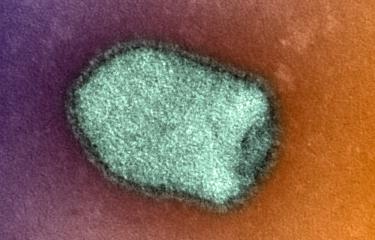

The rabies virus (genus Lyssavirus) is found in the saliva of infected animals such as dogs, cats, bats and other wild mammals.

How does the virus spread?

Rabies is usually transmitted through direct contact with the saliva of a contaminated animal, via a bite or scratch or if the animal licks broken skin or mucosa. Human-to-human transmission (through organ transplants or from mother to fetus) is extremely rare.

What are the symptoms?

The rabies virus is neurotropic: it infects the nervous system and prevents it from functioning properly. The virus does not cause visible lesions in the brain but it disrupts neurons, especially the autonomic nervous system, which regulates heart rate and breathing. After an average incubation period of one to two months, the infected individual develops encephalitis symptoms.

The symptomatic phase involves various neurological disorders, especially anxiety, agitation and fluctuations of consciousness, as well as dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system (excessive salivation, fluctuations in heart rate and blood pressure, etc.). Hydrophobia (involuntary spasms of the muscles in the neck and diaphragm at the sight of water) is sometimes observed. Once the symptoms appear, the disease leads to coma and death within a few hours or a few days.

Apart from a few cases reported in children, the outcome is always fatal after the onset of clinical signs.

How is rabies diagnosed?

Rabies is diagnosed in humans on the basis of virological tests performed in a reference laboratory (the National Reference Center (CNR) for Rabies at the Institut Pasteur is the only laboratory in France authorized to perform these tests). The virus is generally identified by PCR based on saliva samples or a skin biopsy.

What treatments are available?

Preventive treatment of rabies following exposure to a suspected rabid animal involves cleaning all wounds immediately (with water and soap for 15 minutes) followed by careful application of an antiseptic. A tetanus test is also recommended after a bite, as well as antibiotic prophylaxis in certain cases.

Post-exposure prophylaxis (preventing the onset of symptoms after exposure to a suspected rabid animal) involves vaccination, together with the use of anti-rabies serum for severe cases of exposure. The treatment must be administered rapidly after exposure, before the appearance of the first symptoms, which signal the start of an inevitably fatal decline.

Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) consists of 4 or 5 intramuscular injections over the course of a month and is well tolerated.

Several countries also use a shorter prophylaxis regimen administered by intradermal injection, recommended by WHO since 2018. It is thought that every year around 17 million people receive rabies post-exposure prophylaxis worldwide.

In 2023 in France, 3,016 people received post-exposure prophylaxis, 70% of whom had been exposed abroad. This does not necessarily mean that these people had been exposed to the rabies virus, but rather that the risk of transmission could not be ruled out and prophylaxis was administered as a precaution.

Has anyone ever survived rabies without receiving treatment?

There are only a few very rare cases of survival without post-exposure prophylaxis. Surviving rabies is an exceptional occurrence, the best-known case being an American teenager who survived the disease in 2004. She was bitten on the American mainland by a bat and was not vaccinated for rabies before or after exposure. After receiving aggressive treatment in intensive care, she survived and recovered with few after-effects. While this case opened up new prospects in terms of treatment, the reason for her survival cannot be attributed to the treatment she received; it is probably more likely to have been down to the combination of a particularly effective immune response and a virus that was ill adapted to humans. In the other cases, survival after proven rabies infection has led to severe after-effects, and no curative treatment has been identified to date.

How can rabies be prevented?

Prevention is mainly based on preventive vaccination of pets, especially dogs and cats, and at-risk populations, as well as control measures for wild animals in certain regions. Campaigns to inform people of the risks of rabies and the measures they should take to avoid contact with suspected rabid animals are also crucial.

A preventive vaccine is available for people at high risk, such as veterinarians or travelers to certain regions.

Lastly, post-exposure prophylaxis is administered to anyone exposed to a suspected rabid animal.

It is important to keep your distance from wild animals – bats, monkeys, etc. – in all world regions, and never to touch or feed pets in countries where dog rabies is not under control: mainly Asia and Africa, and also to a lesser extent Central Europe, the Middle East and South America. Any wounds caused by contact with an animal must immediately be washed thoroughly with water and soap for 15 minutes.

How many people are affected?

It is estimated that rabies is responsible for around 59,000 deaths worldwide each year, mainly in Asia and Africa, most often following a bite from a rabid dog. The reason for these deaths is the failure to implement rabies control measures in dogs in these countries and the difficult access to post-exposure prophylaxis for the most vulnerable populations.

Rabies in France

France (apart from French Guiana) has been free of rabies in pets and terrestrial wild animal populations for more than 20 years. Rabies in dogs was eliminated in Western Europe in the early 20th century, and rabies in red foxes was eliminated via oral vaccination programs among wildlife in the late 20th century. So there is currently no risk of rabies transmission by a non-flying mammal in France (apart from in French Guiana).

The following situations represent a risk of rabies transmission and advice should be sought at an anti-rabies center:

- Bites, scratches or saliva touching a wound or mucosa in another country (and in French Guiana) where rabies still circulates in dogs or wildlife – this mainly affects travelers to Asia, Africa, America and Eastern Europe. The most recent diagnosed case of rabies in a traveler was in 2023; the patient had been bitten by a cat in Morocco two months previously and had not been given post-exposure prophylaxis.

- Contact with bats that may be infected with viruses related to the rabies virus in all world regions, including in France (in mainland France, a patient was contaminated by Lyssavirus hamburg (EBLV-1) in August 2019 (see An exceptional case of rabies in France transmitted by a bat). This was the first case of rabies contracted in mainland France since 1924). Since 2008, four cases of human rabies have been diagnosed in French Guiana, caused by a virus closely related to those circulating in hematophagous bats in Latin America.

- Contact with mammals imported illegally into France less than 6 months previously or that were imported without a valid rabies vaccination from a country where dog rabies is present.

November 2024