In 1983 the AIDS virus, HIV, was isolated by virologists at the Institut Pasteur. Forty years later, HIV-positive patients can live with the virus if they are diagnosed in time and receive the right treatment. Treatments are constantly being improved – great strides are being made as a result of close cooperation between patients, caregivers and scientists. They are the bedrock of the 40-year fight against HIV – as Marc Dixneuf, CEO of the French charity AIDES reminds us.

|

This interview is the fourth in a series of testimonies from representatives of patient organizations to mark the 40th anniversary of the discovery of HIV. |

In 2011, the concept of "Treatment as Prevention" (TasP) emerged. It was proven that HIV-positive people receiving antiretroviral therapy could no longer transmit HIV. And that changed their lives – it changed their relationships with others, with their families and close friends, it took away their fear of transmitting the virus to sexual partners.

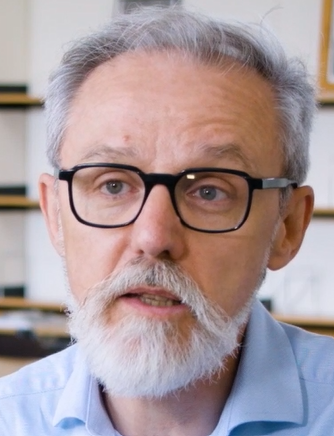

Marc DixneufCEO of AIDES

What has changed over the past 40 years for people living with HIV?

Marc Dixneuf: From my point of view, one of the major changes of the past 40 years has been the role of treatment in prevention.

In 2011, the concept of "Treatment as Prevention" (TasP) emerged. It was proven that HIV-positive people receiving antiretroviral therapy could no longer transmit HIV. And that changed their lives – it changed their relationships with others, with their families and close friends, it took away their fear of transmitting the virus to sexual partners.

The second milestone in terms of treatment was pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). In 2012, it was demonstrated that antiretroviral therapy could prevent people at risk of exposure to HIV from being infected. This meant that those people were able to say: "I can't use a condom, or not always, but if I take PrEP then I am protected."

The impact of these developments was felt at many different levels: there was an effect at an individual level, with repercussions on people's daily lives, and there was a collective effect in terms of controlling and managing the epidemic. But it also restored the balance of power between caregivers and people living with or exposed to HIV, with the latter now free to make choices about their sexuality, their means of prevention and their life.

What scientific discoveries have made a real difference?

M. D.: After the development of the first treatments in 1996, research continued with the aim of identifying new treatments. This meant that patients could be treated at different stages of viral replication in the body, and it also offered solutions for people whose treatment was no longer effective. Some people who had been receiving treatment for several years were no longer responding to their treatment and were dying of AIDS.

To tackle these cases, scientists tirelessly pursued their work over many years and developed new therapeutic strategies. Their efforts often remain under the radar because everyone knows that the first treatments arrived in 1996, but it's very important to acknowledge their work.

You have brought along a photo of Yves Yomb. Can you tell us about it?

M. D.: This photo of Yves Yomb, taken in 2017 at the IAS Conference on HIV Science in Paris, represents a great deal in the fight against HIV. First, it indicates a shift in the importance attached by the French government to the fight against HIV, because the French President chose not to attend this international conference in person.

The other major change was that Yves Yomb, a gay HIV activist from Cameroon, gave a first-person account of his own experience – what life was like in Cameroon for a homosexual man living with HIV. By sharing his story, he chose to break the silence.

But it was nevertheless that silence that killed him two years later, when he was in France for the Replenishment Conference of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, and had to be admitted to hospital. It had taken too many weeks to identify the cancer that was killing him.

Why am I sharing his story? Because it's all very well to have available treatments, to be able to speak in public, to be a key figure in the fight against HIV, but silence, the inability to talk about your condition (because of your family, social pressure, etc.) can still kill you because it leads to delays in diagnosis. And what killed Yves was human papillomavirus (HPV), a virus that kills many people living with HIV.

What message would you like to share with scientists?

M. D.: I would like to say to them that our door is always open if they want to come and talk to us. Knowledge, laboratories, research – which is extremely competitive and demanding for scientists – can be isolating. In the fight against HIV, one of the first things that scientists did that made a real difference was that they spoke to patients, to charities. And that's the message that I want to pass on to young scientists: always feel that you can reach out to charities, feel free to open up your labs to us, like your predecessors or Françoise Barré-Sinoussi did, because it is by working together that we will find solutions.