A team tackling the mysteries of the microbiota, the brain and the immune system

Every day, the members of the Microenvironment and Immunity Unit directed by Gérard Eberl at the Institut Pasteur focus their efforts on understanding the microbial mechanisms involved in diabetes, obesity, chronic childhood diseases, liver disease and colon cancer. This tireless team of scientists are constantly pushing their boundaries to improve their knowledge of the microbiota and unravel the interactions between the brain and the immune system, with the aim of shedding new light on neurodegenerative diseases. We take a visit to Gérard Eberl's laboratory.

To give you a glimpse of the daily workings of laboratories and the activities of scientists, the Research Journal includes regular features on some of the Institut Pasteur's teams. When we decide to shine a light on a specific research unit, the questions tend to come thick and fast. The scientists also have their fair share of questions to grapple with every day. With these regular "lab reports", we take you behind the scenes to find out more about each individual's work, role and hopes for the future.

Gérard Eberl's laboratory is on the ground floor of the Metchnikoff building, named after the famous Russian scientist Ilya Mechnikov – recruited by Louis Pasteur and co-laureate with Paul Ehrlich of the 1908 Nobel Prize in Medicine for his work on immunity.

The research unit explores the mechanisms that our body uses to defend itself. The primary aim is always to improve understanding of living processes, before envisaging potential clinical applications. That's what basic research is all about. How does our immune system attack pathogenic bacteria? What is the role of the microbes that populate our body in such vast numbers? At what point does a microbe become a threat – and why? These are some of the questions that Gérard Eberl's team is trying to address by studying the microbiota, the complex ecosystem of microorganisms (bacteria, fungi, viruses, etc.) that live in and on us (on our skin, in our stomach and lungs, etc.) and are involved in such wide-ranging tasks as digesting food, helping protect against pathogens and producing vitamins. Our immune system, which serves as a defensive barrier for the human body, lives alongside our various microbiotas, which play an integral part in its proper development.

Can excessive hygiene give rise to new diseases?

The research currently being carried out in the Microenvironment and Immunity Unit can be traced back to the contribution that Louis Pasteur – and others in the late 19th century such as Joseph Lister – made to human health by championing hygiene measures. A huge number of lives were saved thanks to the introduction of habits that have now become second nature, such as handwashing and sterilizing surgical instruments in hospitals.

The impact of many infectious diseases, including tuberculosis, rabies, measles, smallpox and polio, fell dramatically. Conversely, however, inflammatory disorders such as allergies, diabetes and multiple sclerosis became rife. "It's as if we had to pay the price for (almost) getting rid of infections," laments Gérard Eberl. The hygiene theory is based on the idea that the absence of some microbes could disrupt the balance of the microbiota. "It has already been observed in clinical research that the earlier a child is exposed to antibiotics, the more that child will suffer from allergies and inflammatory diseases – in proportion to the quantities of antibiotics used," explains the scientist.

It is therefore believed that allergens can have a much more virulent effect on individuals that were not exposed to certain microbes early in life. This imbalance of the gut microbiota could have a variety of consequences – including a neurodegenerative impact (see the "Microbes & Brain" Major Federating Program) – later on in the lives of individuals who are particularly susceptible to inflammatory disorders. So should we revert to a more relaxed attitude to hygiene – and run the risk of seeing some infectious diseases make a comeback? Gérard Eberl and his team are trying to pinpoint the optimal point on this sliding scale, and their work has direct clinical applications: they are hoping to develop preventive methods to tackle allergies in children.

From left to right:

Ziad Alnabhani, Ferdinand Jagot Brunner, Gérard Eberl, François Déjardin, Sophie Dulauroy, Marion Rincel, Emelyne Lécuyer, Tinhinan Fali, Lucette Polomack, Jaechan Ryu, Bérengère Hugot, Maud Pascal and Stephen Cornick,

Several conditions under the microscope – from diabetes to colon cancer

The unit is divided into three thematic groups:

- microbiota (understanding the impact of the microbiota on white blood cells),

- nervous system (studying the impact of nerve cells on immunity), and

- immune system (studying white blood cells themselves).

There are fourteen staff members in the unit. PhD students, post-doctoral fellows, engineers and technicians all contribute their respective expertise with one goal in mind: improving their understanding of the microbial mechanisms that play a role in the development of disorders such as diabetes, obesity, chronic inflammatory diseases (Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis), liver disease and colon cancer.

The team members come from all over the world – France, Israel, Brazil, Canada, Korea, Japan and Switzerland – but they all speak the same scientific language, and they are all committed to making a real contribution to the unit's projects – while they are working there. For many of these scientists are only in the unit on a temporary basis. Unlike technicians and engineers, sometimes several post-doctoral fellows come and go over the duration of a single project.

"The real backbone of research is PhD students and post-doctoral fellows," sums up Gérard. But without the technicians and engineers, there would be no continuity in the team's knowledge and experience. Just like with the microbiota, it's all about finding the right balance that will allow the group to work together in harmony.

At New York or Harvard University, you sometimes need to take a bus to go and see a colleague. At the Institut Pasteur, scientists can meet up easily at the drop of a hat, just by crossing the road.

Gérard Eberl initially completed studies in Switzerland before going to New York for a post-doctoral position: "I worked on an intriguing molecule that might link the immune system with the nervous system. That led me to study specific white blood cells involved in the development of the immune system." He joined the Institut Pasteur via a five-year group. In 2005, his research proposal was accepted and he set up the Lymphoid Tissue Development group.

He appreciates the working environment at the Institut Pasteur because of its illustrious history, its attractiveness at global level, and also the cross-disciplinary nature of its research fields and the proximity of the laboratories: "New York and Harvard University are great but you sometimes need to take a bus to go and see a colleague," he notes. At the Institut Pasteur, scientists can meet up easily at the drop of a hat, just by crossing the road.

Helping identify each individual's talents

The timetable of a Head of Unit and Principal Investigator (PI) is a busy one, involving leading his team's activities – "you need to be on hand to discuss the science, the experiments" –, devising research projects and seeking funding for them, conducting appraisals and teaching. And, of course, publishing: "A Principal Investigator is responsible for guaranteeing the excellence of the research carried out and promoting its visibility." Gérard Eberl is also Head of the Department of Immunology at the Institut Pasteur.

As well as sometimes readjusting his team's projects, he also provides moral support when doubts creep in: "Each person is designed to carry out a role, and is perfectly suited to that role. One of the important tasks of a Head of Unit is to identify each individual's talent. I am also there to advise students and post-doctoral fellows about their career development."

The relaxed, friendly atmosphere in the unit can undoubtedly be attributed in part to Gérard Eberl's management style – he gives his staff a good deal of freedom – and also to the more informal moments, which provide the team members with an opportunity to see a different side to their colleagues. This is vital to let off steam when the pressure to publish gets too much: "I remember that for one project, we submitted our results to be published – the culmination of several years of research – and the publication was turned down. It was a bitter blow for the laboratory. In the end, we rewrote the articles in a different way, and we managed to get two publications in the leading journals in the field. Our initial distress turned to joy," recalls Gérard Eberl. Such highs and lows are an inevitable part of research.

Interacting with others to challenge ideas

All the team members manage their projects independently. "I meet those working in the lab on a regular basis – some once a week, others once a month. We talk about how their experiments are progressing and whether their approach is justified," explains Gérard Eberl. Scientists generally tend to lead a solitary working life. Sometimes they are assisted with their lab work, but on the whole they are immersed in their projects by themselves, before showing the results of their research to colleagues. Alone, faced with the infinitely small details of life: "A single cell type can give rise to an entire project," notes François, the team's engineer, illustrating the incredibly minute levels of detail that characterize today's research. A project lasts between 5 and 7 years on average, and may in turn open up new projects.

Regular meetings with the rest of the team and the other units in the department break up the relative solitude of the team members. Every Thursday, from 12 noon to 2pm, they hold a "lab meeting", where they discuss day-to-day working activities. Then a PhD student or post-doc will present their "raw" research results. Everyone discusses the results together and tries to resolve any problems encountered. "It's a great opportunity to hear the views of all the other staff members in the meeting and broaden our perspective," says Sophie, the laboratory technician. It is vital for the scientists to be able to shift the focus of their experiments and lab work at any point to make sure they keep on the right track. The time spent on research is lengthy and precious, and there are countless dead ends. It's an exploratory process in which the scientists need to constantly challenge their ideas – especially thanks to the valuable input of their peers.

Collaboration with neuroscience experts

Interdisciplinarity is a core tenet of research at the Institut Pasteur. But seeing the human body as a complex and interconnected whole is a relatively recent scientific approach. Scientists had to start by developing a thorough knowledge of each separate system (such as the immune, vascular, digestive and nervous systems) before they were able to examine the interdependence of these systems. "We can now measure the extent to which the brain is involved in immune responses," emphasizes Gérard. This promising new frontier merits a concerted research effort. And the Institut Pasteur campus, with its extensive gamut of research fields – microbiology, immunology, neuroscience, etc. – is an ideal melting pot that encourages close collaboration with other laboratories. Four members of the Microenvironment and Immunity Unit work on neuroimmunology in cooperation with Pierre-Marie Lledo, Head of the Perception and Memory Unit. And the Stroma, Inflammation and Tissue Repair Unit, directed by Lucie Peduto, also takes part in the team's lab meetings.

Perseverance is vital

The scientists' research is guided by a twofold objective:

- first, the lofty goal of improving understanding in the hope of finding cures. Could Alzheimer's disease be partly caused by an imbalance in the gut? What role does the immune system play in the development of Parkinson's disease? These broad issues are always in the minds of the scientists in Gérard Eberl's team. The key is to ask the right questions, carry out experiments and improve understanding. And hopefully their efforts might lead to a crossover to clinical research. "Although we have chosen to focus on basic research, we have developed cooperation with clinicians. Sometimes our basic research is much closer to clinical applications than we might first think," explains Gérard. Basic research is an exploratory process, and the scientists never know in advance at what point it might be possible to develop clinical applications based on their discoveries.

- the second goal, a more tangible one, is publications – the means by which science, and our knowledge of the living world, can advance. It's all about making sure research lives on beyond the laboratory. But publishing alone isn't enough. "We need to publish a lot, and publish well, in the best-rated scientific journals, those with the highest impact factor," explains Emelyne, a post-doctoral fellow in the unit for the past two years. The entire system of research funding is based on this principle. A project that gives rise to quality publications generates new funding, either to continue with the same project or to spin off new ones, which in turn will also generate budgets.

The profession of scientist isn't so different from many others: "It's vital to produce quality work. It's vital – but it's not always enough," says Gérard Eberl. "You can be doing excellent work, but on a false premise," he continues. And that can create extraordinary pressure. "When you're working on a project that can last for nearly a decade with all the research that needs to be carried out, there are many moments of uncertainty. It can be tempting to throw in the towel," he says, before pointing out that "the most important character trait for a scientist is perseverance – accepting frustration and failure and being able to pick oneself up and start again!" Given the pressures of the job, it's not hard to understand why.

Emelyne Lécuyer, post-doctoral fellow

Emelyne joined Gérard Eberl's unit in 2016 for her second post-doctoral position. She works on type 3 innate lymphoid cells – her aim is to elucidate the role of these cells by carrying out experiments on their native function.

With her university background (a Master's in Nutrition and a PhD in an immunology lab), she was a perfect fit for a unit like Gérard Eberl's. "I arrived here because my research was at the crossroads of immunology and metabolism," she explains.

A typical day for Emelyne involves planning the day's experiments and keeping a close eye on developments in the lab. She uses techniques that enable her to confirm or rule out her initial hypotheses. On Thursdays, at the lab meetings, she presents her results to the other members of the unit and raises any problems she has encountered. The scientific discussion that follows enables her to continue her research with a fresh perspective.

The project she is working on began in 2011. She is the third post-doctoral fellow to take up the position. François, who has been the team's engineer for the past six years and is working closely with her on the project, knew her two predecessors.

For Emelyne, the Institut Pasteur is a place that is conducive to high quality research. "It's a campus where great science happens – innovative, collaborative and international science," she says. "The technical platforms are outstanding – they offer virtually all the latest cutting-edge technologies." Even though her unit focuses on preclinical research, "we provide answers to questions about pathophysiological mechanisms of action, and our hypotheses can then be tested clinically with patient biopsies," she explains. In basic research, it is becoming increasingly important to look beyond the lab, to establish a link between the topic of study and the potential for improving future clinical realities.

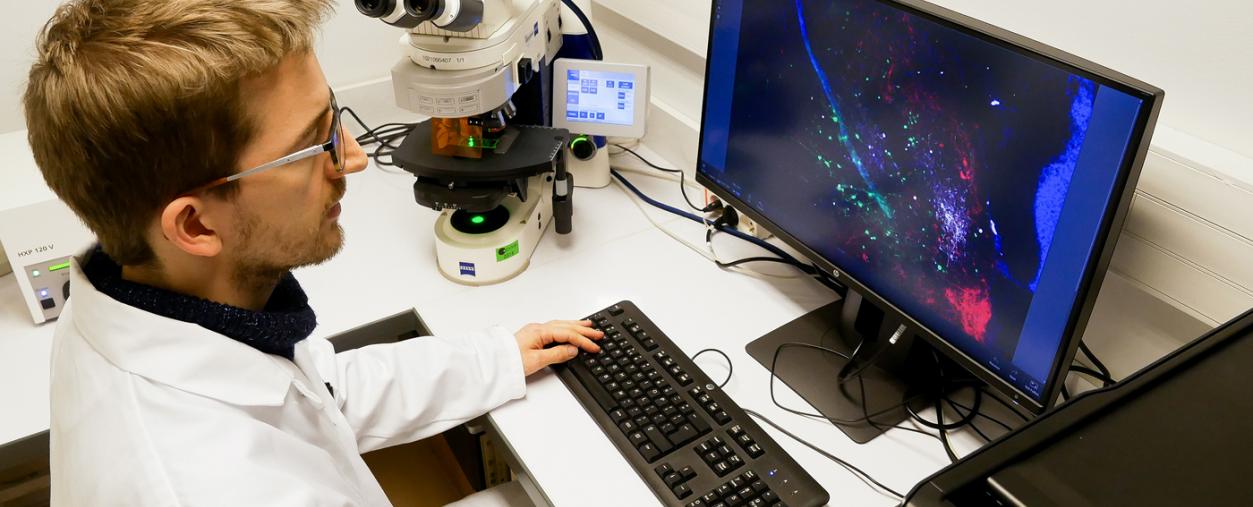

François Déjardin, research engineer

François is the laboratory's engineer. He is 31 years old and completed a Bachelor's degree in his home city of Nancy before heading to Toulouse for his Master's. He carried out his second-year Master's internship at the Institut Pasteur in a protein production platform. As a specialist in laboratory procedures involving molecular biology and biochemistry, François joined Gérard's team in October 2012.

He is working on a technological research project. "I am developing a strategy to modify cells at genome level," he explains. The aim is to make this new technique available to scientists so that they can use it for new projects. This is another key tenet of the research process: technological progress should pave the way for scientists to address new questions. François also specializes in laboratory techniques such as fluorescence microscopy and fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), a method of selecting and separating cells that have been labeled. "Each cell expresses different protein combinations that can be classified into populations," explains François. Another technique is quantitative PCR (qPCR), which can be used to determine gene expression, helping scientists to understand what cells produce in certain contexts (pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory proteins, etc.). The aim of all these techniques is to analyze cell behavior in the event of infection or disease.

François helps Emelyne with her project and also spends time on his technological development projects. He sometimes fosters links with other units at the Institut Pasteur. He very much appreciates the Institut Pasteur's international reach, and also the possibilities for internal mobility: the Institut Pasteur is such a melting pot of research fields, "an outstanding pool of expertise," as François describes it, that a cross-disciplinary profile like his could find a home in several laboratories on the same site – paving the way for a long and successful career.

Sophie Dulauroy, technician

Sophie joined Gérard Eberl's unit in July 2007.

Her cross-cutting work in the team means that she has an important part to play in maintaining continuity. "Sophie is the key!" smiles Gérard Eberl. PhD students and post-doctoral fellows only stay in the unit for a short time, so permanent staff are needed to show newcomers the ropes. But her role goes much further: Sophie masters the techniques of molecular biology, RNA extraction, DNA synthesis and sequencing. The team's scientists, like current post-doc Ziad, often make use of her expertise, which can save them a good deal of time.

So Sophie's work is not as solitary as that of some of the others. And she also has something to do with the good atmosphere among the staff in the unit. She often organizes informal events. "Maybe it's linked to the nature of our work during the day, but we do enjoy spending time together some evenings, to unwind," she says. These opportunities to meet up away from the lab encourage the development of real friendships with colleagues who are often only there for a short time. "It can be hard to see people leave – it's the story of my life: people join the lab only to head off elsewhere a few years later!" she says ironically. But they never completely lose contact – each individual leaves a lasting impression.