On Monday April 30, 2018, the French Ministry of Health announced that it was stepping up surveillance of the tiger mosquito, Aedes albopictus, which is now present in 42 French départements – twice as many as two years ago. But just how dangerous is this mosquito, vector of diseases such as dengue, chikungunya or zika?

The tiger mosquito (see What is the "tiger mosquito" (Aedes albopictus)?) is continuing to colonize France, with some 62 départements now affected, as reported by the French General Directorate of Health in April. 42 départements are on red alert and 20 are on orange alert (see the maps below). On April 30, 2018, the French Ministry of Health announced that it was stepping up surveillance of the tiger mosquito with the aim of slowing its progression and "reducing the risk of the importation and spread on French mainland of the viruses it may carry".

Why is Aedes albopictus gaining ground in France?

Several factors come into play. First, Aedes albopictus is extremely good at colonizing new areas. Like all mosquitoes, it reproduces quickly and easily. When the female matures, if the atmospheric temperature is favorable, she mates. Although like the male she feeds on plant sap, in order to reproduce she needs to feed on blood – she is "hematophagous". Once she has bitten an animal or human, she goes off in search of a damp habitat in which to lay her eggs. Some mosquitoes like wide open spaces, such as the banks of lakes or dead tributaries of rivers, but Aedes albopictus prefer to lay their eggs in smaller breeding grounds, such as holes in trees, flower-pot saucers, tires and such like. The eggs then hatch into larvae, which develop into pupae and then adult mosquitoes.

So dry conditions can be harmful for Aedes albopictus?

Unfortunately not. Although a lack of water is fatal for the progeny of some species, Aedes albopictus can adapt to this situation. Their eggs can lie dormant in dry conditions for several months without hatching. A day or two after the damp conditions return, the eggs hatch and resume their normal cycle, which lasts from 10 to 15 days. Once they reach the adult stage, mosquitoes live for a period of between three weeks and several months. Given that a female lays 100 to 200 eggs every five days, half of which will produce more females, they are highly efficient at colonizing new areas.

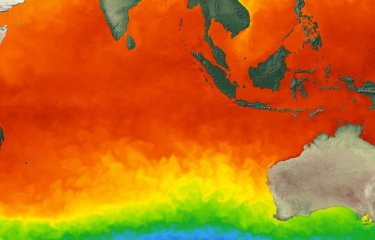

Warm temperatures encourage mosquitoes, but do they also increase the risk of disease transmission?

Yes. The hotter the climate, the faster viruses multiply. Mosquitoes become contagious at an earlier stage. So tropical regions are generally more exposed than temperate regions. In hotter weather, people also spend much more time outside, so logically they come into closer contact with mosquitoes, which are mainly active in the early morning and at twilight. Socio-economic levels also have an impact. In areas with no street cleaning or mosquito control services, mosquitoes proliferate more easily. Similarly, Aedes albopictus (like Aedes aegypti) – which love to breed in little nooks and crannies – can easily find any number of breeding grounds in poorly maintained urban areas. Lastly, in areas where both human and mosquito populations are dense, the risk of disease transmission is higher.

Why does Aedes albopictus not systematically cause disease outbreaks in Europe?

In Europe, the conditions are still far from favorable for disease outbreaks. However, we know that the tiger mosquito has now spread across half of France. So we need to be vigilant, as we have some concerns about what will happen when mosquito eggs start to hatch in the first spring rains.

What strategies are planned to eradicate these mosquitoes?

The main problem is that Aedes albopictus mosquitoes (much like Aedes aegypti) have developed resistance to insecticides. We therefore need to explore other avenues. One of these is to wipe out the mosquitoes. For example, we can irradiate males in order to render their sperm inefficient, so that they are unable to reproduce. We can also genetically modify them to make them dependent on an antibiotic. This will make their progeny similarly dependent and they will ultimately die out because the antibiotic is unavailable in their natural habitat. Lastly, small-scale trials are under way involving mosquitoes that carry a bacterium which is harmless to humans but prevents mosquito eggs from hatching. The main downside of all these techniques is that nature abhors a vacuum, and so eliminated mosquito populations will be replaced by others. For example, on Reunion Island, when Aedes aegypti was eradicated from towns, Aedes albopictus, which had previously been restricted to forest regions, took its place.

This is why we are studying a way to render mosquitoes incapable of transmitting viruses. The idea is to stimulate their immune system so that viruses are destroyed before reaching the saliva and cannot be injected into humans through a mosquito bite. Of course, it is always possible that they will counter this attack – we are in the throes of an escalating arms race between virus and mosquito.

Read the full report on "the Geopolitics of the Mosquito"

Maps showing the distribution of the tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus) in mainland France

The tiger mosquito essentially lives in urban areas. Because of its anthropophilic nature (preference for human habitats), once it has arrived in a town or region, it is practically impossible to get rid of it. The French départements where the tiger mosquito is present and active, in other words settled and breeding, are classified as level 1 in the French national plan to prevent the spread of chikungunya, dengue and Zika. To date, no level 1 département has returned to level 0a or 0b. The level of the tiger mosquito's presence in a given département is determined by public mosquito control experts.

Distribution in January 2018 (in French)

Changing situation from 2004 to 2017 (in French)

Source: French Ministry of Health.

For more information, please visit