Where did SARS-CoV-2 come from? How did this virus enter the human population? These questions still remain unanswered. In June 2022, a group of experts, the Scientific Advisory Group for the Origins of Novel Pathogens (SAGO) commissioned by the World Health Organization (WHO), published a report on the origin of coronavirus but was unable to draw a definitive conclusion. Since then, research has continued, particularly at the Institut Pasteur and in the Pasteur Network, to further our knowledge of SARS-CoV-2 and the evolution of the disease in a bid to better understand the origins of the pandemic. To this end, a recent study led by Institut Pasteur scientists on SARS-CoV-2-related viruses circulating among bats in Laos has concluded that it is unlikely that these viruses had acquired the same ability as SARS-CoV-2 to infect human lungs by accumulating mutations during prior silent circulation in human or intermediate host populations. This article explores their research.

The official WHO announcement regarding a novel circulating coronavirus, later named SARS-CoV-2, was made on January 9, 2020. The virus that led to the COVID-19 pandemic is estimated to have caused approximately 15 million deaths worldwide (WHO source on excess mortality associated with COVID-19 between January 1, 2020 and December 31, 2021).

Coronavirus origins: the subject of extensive research

In March 2023, with the pandemic not yet entirely over, the origin of SARS-CoV-2 remains a subject of debate. WHO conducted a survey on this subject in Wuhan in January and February 2021, and SAGO (the Scientific Advisory Group for the Origins of Novel Pathogens), which was commissioned by WHO, published its report2 in June 2022 but was unable to draw a definitive conclusion. Scientific papers published in Science3 in August 2021 and in Cell4 in September 2021 also addressed this question.

Coronavirus origins: three hypotheses within the scientific community

Since coronaviruses are commonly found in bats, SARS-CoV-2 could have been transmitted to humans from this reservoir. There are around 1,500 species of bat, in which several hundred coronaviruses have been described. Certain of these coronaviruses are very similar to SARS-CoV-2, some with over 96% sequence identity between bat coronaviruses and SARS-CoV-2. A key question is to understand the molecular mechanisms and transmission dynamics that could have transformed a bat virus into a closely related virus that has become highly transmissible in humans.

More generally, about the origins of SARS-CoV-2:

The description of the first cases of SARS CoV-2 in the vicinity of Wuhan market supports the hypothesis that the virus crossed the species barrier naturally from an intermediate host sold at this location (see ref. 3 and ref. 4 below). Scientists consider that the "zoonotic" hypothesis is the one most likely to explain the origins of SARS-CoV-2, but research must continue before it can be formally established. "Spillover" from one species to another, directly from a wild-animal reservoir or from an intermediate host, has already been demonstrated for many other viruses. It can be followed by human-to-human transmission (HIV, Ebola, SARS, etc.), but not always (avian influenza). The underlying adaptive mechanisms are varied.

A second hypothesis, developed in the SAGO report², cannot be ruled out but has yet to be scientifically proven: the possibility of introduction of SARS-CoV-2 to the human population through a laboratory leak, whether this leak concerned a coronavirus preserved in its natural form or a coronavirus modified in the laboratory, whether deliberately or by accident. The SAGO report states that "additional information [on the institutional implementation of laboratory biosafety and biosecurity practices] will need to be obtained and reviewed to make conclusive recommendations."

Finally, the hypothesis that the virus was manufactured in a lab for subsequent introduction to the population is rejected by almost the entire scientific community. This hypothesis has been supported mainly by fake news and controversial articles lacking any scientific basis.

Read our page Coronavirus: the Institut Pasteur warns against false information circulating on social media

Christophe d’Enfert, the Institut Pasteur's Senior Executive Scientific Vice-President, emphasizes that "research continues, particularly at the Institut Pasteur and in the Pasteur Network, to further our knowledge of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, the evolution of the disease and the origins of the current pandemic."

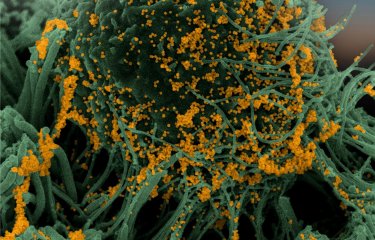

SARS-CoV-2-like sarbecoviruses found in bats

An initial study5 published in Nature in February 2022 reported that researchers from the Institut Pasteur, in particular from the Pathogen Discovery Laboratory led by Marc Eloit, had discovered coronaviruses highly similar to SARS-CoV-2 in fecal swabs from bats in northern Laos, including three sarbecoviruses dubbed BANAL-103, BANAL-236 and BANAL-52. They showed that these viruses bind to the human ACE2 receptor more efficiently than the first SARS-CoV-2 strains sequenced at the start of the outbreak in Wuhan, and that they can replicate in human cells.

However, a further finding was that the spike proteins of these sarbecoviruses lacked the furin* cleavage site, an important determinant of SARS-CoV-2 pathogenicity and transmissibility by respiratory route, which was present in the SARS-CoV-2 virus circulating in the human population from the beginning of the epidemic. This cleavage site plays a key role in mediating viral entry into respiratory epithelial cells (particularly those in the lungs).

* Furin is a ubiquitous protease that cleaves the virus' spike protein. Cleavage of this protein on the surface of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus enables it to infect respiratory cells.

In search of the evolutionary dynamics of COVID-19

In a new study1 published on March 6, 2023 in EMBO reports, scientists from the Institut Pasteur, Université Paris Cité and the École Nationale Vétérinaire d'Alfort (EnvA) analyzed the pathogenicity (for humans) and transmissibility of the three viruses identified in bats living in their natural habitat in Laos.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the possibility of understanding the origin of the COVID-19 epidemic. To this end, the scientists developed the hypothesis of human infection with these three bat viruses before the first clinical cases of COVID-19 appeared in late 2019, and prior to the emergence of human-adapted strains that were more transmissible and pathogenic. They then used animal models to investigate the clinical, epidemiological and evolutionary consequences of a potential species jump to humans of one of them (the BANAL-236 virus).

As Marc Eloit, last author of this new study, explains: "When considering a potentially natural origin for any epidemic and attempting to trace the origins of a zoonosis, it is essential to meticulously verify the different stages of infection in human populations, and, where possible study the closest ancestral pathogen directly."

This study has shown that these viruses have low pathogenicity and transmissibility in humans, associated with reduced respiratory tropism. Furthermore, the researchers concluded that it is highly unlikely that a furin cleavage site was acquired in the spike protein of BANAL 236 during prior silent circulation in humans or, more probably, in other permissive species.

If SARS-CoV-2 arose from an evolution of BANAL 236 and acquired this furin cleavage site, Marc Eloit's team believes that this acquisition is more likely to have been by recombination** prior to an effective species jump, because the resulting viruses could then have been selected given their advantage of being transmissible by respiratory route.

** Recombination is an exchange of genetic material, usually between viruses or with cellular sequences

At the same time, the scientists showed that mice infected with the low- or non-pathogenic bat virus BANAL-236 were subsequently protected from SARS-CoV-2, which was to be expected because of the similarities between the viruses.

Lastly, the scientists studied the serological status of people commonly exposed to bats in Laos for occupational reasons, in the precise area where the viral strains had been isolated in the previous study. They found no serological evidence of infection with bat sarbecoviruses, confirming the low transmissibility of these viruses.

"This research in the lab and in animals, complemented by the serological study in people in close contact with bats, shows that it is unlikely that the acquisition of the furin cleavage site by BANAL 236 virus occurred during prior active, silent circulation in humans or other permissive species, i.e. those in which the virus can replicate," concludes Marc Eloit.

Ref. 1. SARS-CoV-2-related bat virus in human relevant models sheds light on the proximal origin of COVID-19, EMBO reports, March 6, 2023

Article published as a preprint on Research Square, June 30, 2022

Sarah Temmam1,2,†, Xavier Montagutelli3,†, Cécile Herate4,†, Flora Donati5,6,†, Béatrice Regnault1,2, Mikael Attia5, Eduard Baquero Salazar7, Delphine Chretien1,2, Laurine Conquet3, Grégory Jouvion8,9, Juliana Pipoli Da Fonseca10, Thomas Cokelaer10, Faustine Amara5, Francis Relouzat4, Thibaut Naninck4, Julien Lemaitre4, Nathalie Derreudre-Bosquet4, Quentin Pascal4, Massimiliano Bonomi11, Thomas Bigot1,12, Sandie Munier5, Felix A Rey7, Roger Le Grand4, Sylvie van der Werf5,6 and Marc Eloit *,1,2,13

1. Institut Pasteur, Université Paris Cité, Pathogen Discovery Laboratory, Paris, France

2. Institut Pasteur, Université Paris Cité, The OIE Collaborating Center for the Detection and Identification in Humans of Emerging Animal Pathogens, Paris, France

3. Institut Pasteur, Université Paris Cité, Mouse Genetics Laboratory, Paris, France

4. Center for Immunology of Viral, Auto-immune, Hematological and Bacterial Diseases (IMVA-HB/IDMIT), Université Paris-Saclay, Inserm, CEA, Fontenay-aux-Roses, France

5. Institut Pasteur, Université Paris Cité, CNRS UMR 3569, Molecular Genetics of RNA Viruses Unit, Paris, France

6. Institut Pasteur, Université Paris Cité, National Reference Center for Respiratory Viruses, Paris, France

7. Institut Pasteur, Université Paris Cité, CNRS UMR 3569, Structural Virology Unit, Paris, France

8. Ecole Nationale Vétérinaire d'Alfort, Histology and Pathology Unit, Maisons-Alfort, France

9. Université Paris Est Créteil, EnvA, ANSES, DYNAMYC Unit, Créteil, France

10. Biomics Platform, C2RT, Institut Pasteur, Université Paris Cité, Paris, France

11. Institut Pasteur, Université Paris Cité, CNRS UMR 3528, Structural Bioinformatics Unit, Paris, France

12. Bioinformatics and Biostatistics Hub – Computational Biology Department, Institut Pasteur, Université Paris Cité, Paris, France

13. Ecole Nationale Vétérinaire d'Alfort, University of Paris-Est, Maisons-Alfort, France

† These authors contributed equally to this work

* Corresponding author: Institut Pasteur, Paris, France.

Ref. 2. Position of SAGO, the Scientific Advisory Group for the Origins of Novel Pathogens (WHO), June 2022.

Ref. 3. The animal origin of SARS-CoV-2, Spyros Lytras et al, Science, August 2021.

Ref. 4. The origins of SARS-CoV-2: A critical review, Edward C. Holmes et al. Cell. Sept. 2021.

Ref. 5. Bat coronaviruses related to SARS-CoV-2 and infectious for human cells, Nature, February 16, 2022

Article published as a preprint on Research Square, September 17, 2021.