Scientists and physicians are attempting to elucidate the mechanisms of an atypical form of liver cancer in Peru that is mainly affecting young people. Their research has revealed previously unknown risk factors.

Why are young Peruvians developing liver cancer? The highly unusual forms of the disease are attracting the attention of scientists and healthcare workers. Their goal is to prevent, detect and treat this alarming condition, which virtually always proves fatal.

"We work on genetics and hepatitis B virus," explains Pascal Pineau, a geneticist in the Nuclear Organization and Oncogenesis Unit at the Institut Pasteur (Paris). We’ve found a new form of atypical liver cancer in South American patients, and the usual screening methods for hepatitis B infection cannot detect any virus presence in those patients.” This liver cancer specialist has therefore attracted the attention of the Institut de recherche pour le développement (IRD), which had a mission in Lima.

"With our Peruvian partners from the Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Neoplásicas, we have already ruled out a number of risk factors, such as aflatoxin intoxication,1 the use of harmful medicinal plants, and infection by some parasites in the liver," explains molecular biologist Stéphane Bertani, researcher at the IRD. "We have recently pinpointed cell damage that suggests the involvement of a genotoxic agent (a product that is harmful for the genome),2 and we have realized that we were underestimating the importance of occult3 hepatitis B virus infection."4

Primary liver cancer, or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), is the third leading cause of cancer death worldwide. It very often occurs in patients with chronic liver conditions that have already resulted in severe damage to the liver tissue, such as steatosis,5 liver fibrosis or cirrhosis. The typical patient profile is generally men over the age of 45. But this is not the case in Peru. Most patients are young adults, adolescents or even children, both male and female and with no known history of liver disease. They develop tumors that are already large by the time they are detected. To confirm this atypical clinical presentation, the scientists carried out a comparative histological analysis on non-cancerous liver tissue from Peruvian patients with or without hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).6

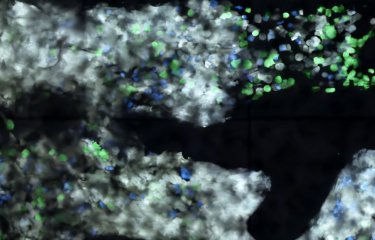

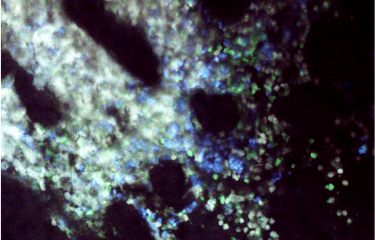

Cellular damage

"In our patients, we recorded very low levels of steatosis, liver fibrosis and cirrhosis, comparable to those in the control group," indicates the specialist. "This confirms that these cases of cancer are not the result of comorbidity associated with the usual chronic liver conditions. But our most significant finding was foci of damaged cells in 61% of the patients with liver cancer." These anomalies were found in significant quantities in the liver tissue, indicating that they could form a precursor environment for tumor formation (tumorigenesis). Very similar damage has already been described in the livers of rats exposed to toxic chemical compounds. "This could suggest that the Peruvian patients are being exposed to an environmental agent that is genotoxic for liver tissue," says Stéphane Bertani. "We therefore need to evaluate the potential role of mycotoxins from Fusarium, a fungus that can often be found in Andean food such as quinoa, kiwicha and kaniwa. We also need to investigate the theory of intoxication by products from the agrochemical industry." Nor are the scientists ruling out the existence of other risk factors. They are particularly looking into the most common risk factor, hepatitis B virus infection.

Elusive viral hepatitis

It came as no surprise when serological testing revealed that 51% of the Peruvian patients with HCC were infected by the hepatitis B virus (HBV). But their viral load was moderate – unlike in other world regions, where the levels recorded are much higher and patients are therefore given antiviral treatment to prevent HCC. "Most interestingly, we discovered very small traces of viral DNA in 30% of the patients that had been classified as seronegative for HBV," indicates Pascal Pineau, from the Institut Pasteur (Paris). "These elusive infections cannot be detected by the usual screening methods." In total, more than 80% of Peruvian patients therefore had HBV DNA in their serum. In Peru, where the incidence of hepatitis B is relatively low, this suggests that the virus nevertheless plays a role in the onset of liver cancer.

"Screening and treatment for hepatitis, especially underlying infections for which hepatocellular carcinoma could be a clinical manifestation, is a challenge," explains pharmacist Eric Deharo, co-author of the studies. "That is why we recently launched the European project Coclican, to identify predictive biomarkers that indicate a risk of progression to cancer for liver infections."

Notes

1. Mycotoxins produced by some fungi proliferate in grains and seeds kept in a warm, humid environment.

2. Cano L., Pablo Cerapio J., Ruiz E., Marchio A., Turlin B., Casavilca S., Taxa L., Marti G., Deharo E., Pineau P. & Bertani S., Liver clear cell foci and viral infection are associated with non-cirrhotic, non-fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma in young patients from South America, Scientific Reports, July 30, 2018.

3. An infection that cannot be detected with common screening methods.

4. Marchio A., Pablo Cerapio J., Ruiz E., Cano L., Casavilca S., Terris B, Deharo E., Dejean A., Bertani S. & Pineau P., Early-onset liver cancer in South America associates with low hepatitis B virus DNA burden, Scientific Reports, August 13, 2018.

5. The build-up of fat in liver tissue.

6. Tissue collected during tumor resection in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma for the first group, and in nodule or liver metastasis ablation for the second.

Courtesy of the Institut de recherche pour le développement (IRD).