What are the causes?

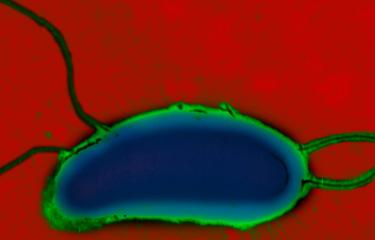

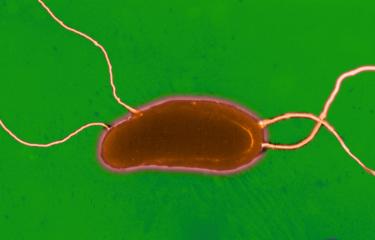

Cholera is caused by a bacterium of the Vibrio cholerae species. Various serogroups of the species exist (there are over 200 of them), though only serogroups O1 (and in rare cases, O139) cause cholera. Moreover, in order to trigger the disease, these bacteria must produce cholera toxin and belong specifically to the El Tor genetic lineage responsible for the seventh pandemic.

How do the bacteria spread?

Vibrio cholerae is a highly motile bacterium with modest nutritional requirements whose natural reservoirs are found in humans. The Ganges Delta is considered a permanent source of new strains of the cholera agent at global level, due to particularly intensive human interaction with the aquatic environment in this location. The disease is caused by ingesting contaminated water or food or via unwashed hands. Once the bacteria reach the intestines, they secrete cholera toxin, the main cause of the severe fluid and electrolyte losses observed, which can reach up to 15 liters per day. Humans serve as both a culture medium and a means of transport for Vibrio cholerae. The vast quantities of liquid stools released are responsible for spreading the bacteria in the environment and for fecal-oral transmission. The incubation period and, in particular, asymptomatic carriage also enable Vibrio cholerae to be transported over varying distances.

The main factors that encourage cholera transmission are low socio-economic status and poor living conditions. Crowded populations in areas with inadequate hygiene facilitate the emergence and development of cholera outbreaks.

What are the symptoms?

In approximately 80% of cases, the infection presents as ordinary diarrhea. However, 10-20% of infected individuals report severe illness. The incubation period ranges from a few hours to a few days. The production of cholera toxin by the bacteria leads to severe diarrhea and vomiting but no fever, with substantial losses of fluid and electrolytes leading to major dehydration. In the absence of treatment, in its most severe forms, cholera is one of the most rapidly fatal infectious diseases: 25 to 50% of patients die within 1 to 3 days as a result of cardiovascular collapse. The death rate is higher among children, elderly people and those with weak immune systems.

How is the infection diagnosed?

Cholera is diagnosed by analyzing stool samples in a laboratory. The bacteria are isolated and characterized as Vibrio cholerae through culturing followed by identification. They can also be detected through an initial PCR test followed by a culture to identify the strain of Vibrio cholerae. Confirmation is provided by the National Reference Center for Vibrios and Cholera if the strain belongs to Vibrio cholerae serogroup O1 (or O139), produces cholera toxin, and belongs to the El Tor lineage responsible for the seventh pandemic.

What treatments are available?

Treatment primarily involves replacing lost fluid and electrolytes. Depending on the level of dehydration, patients are rehydrated orally or by intravenous administration. Improvements can be observed after just a few hours and patients recover fully, with no lasting effects, within a few days.

Antibiotic therapy is useful in severe cases, but given the emergence of multiple-antibiotic-resistant strains of Vibrio cholerae, antibiotic susceptibility first needs to be tested on a representative sample of isolated strains.

How can cholera be prevented?

Improved access to drinking water and general hygiene measures are vital in tackling cholera. In the event of an outbreak, a comprehensive public health response is essential, and health education needs to be developed in countries with regular cholera outbreaks. During a cholera outbreak, WHO allocates vaccines from the global stockpile of oral cholera vaccines (OCVs) created in 2013, which are then administered as part of a reactive vaccination campaign implemented in addition to the above-mentioned measures. This global stockpile of vaccines now needs to be increased to accommodate increasing demand with restrictions on supplies likely to last until 2025.

Two oral vaccines are currently prequalified by WHO:

- Dukoral® (not included in the global stockpile), used mainly for travelers. This vaccine is composed of killed whole cells of Vibrio cholerae O1 in combination with a recombinant B-subunit of cholera toxin. Two doses need to be administered at least 7 days and no more than 6 weeks apart, providing protection 1 week after the second dose is administered. The vaccine provides 85 to 90% protection after 6 months, falling to 60% after 2 years.

- Euvichol® (included in the global stockpile). This vaccine is composed of killed whole cells of Vibrio cholerae O1 and O139. It needs to be administered in 2 doses and is 65% effective after 5 years. However, restrictions on the supply of vaccines have led to 1-dose administration regimens being used in recent years for reactive vaccination campaigns, limiting the period of protection provided.

Euvichol-S®, a new simplified OCV prequalified in early 2024, is due to enter the global market at the end of this year. This will help boost the global stockpile of vaccines.

Vaxchora®, a vaccine that has not yet been prequalified by WHO, is currently available in France. It is composed of a live strain of Vibrio cholerae O1 of the classical biotype with attenuated virulence. It needs to be administered as a single dose.

It is important to emphasize that there is currently no vaccine that provides long-term protection against cholera. Given the threat that cholera still represents and the difficulties in implementing hygiene and sanitation measures in several countries, it is important to continue research on cholera vaccination.

As regards travelers, the French High Council for Public Hygiene no longer recommends routinely vaccinating people traveling to countries with cholera outbreaks (as of 2004). Such routine vaccination may potentially be recommended for health workers traveling to work with patients or in refugee camps during outbreaks. Hygiene measures remain travelers' primary means of prevention:

- Wash your hands

- Consume drinking water only and avoid tap water and ice cubes. If it is not possible to access drinking water, water purification tablets, filters or chlorine should be used. Cloudy/dirty water should be filtered prior to drinking.

- Ensure the food you eat is safe by cooking it properly, eating it hot, keeping it covered, and not eating raw food.

Who is affected?

There have been seven cholera pandemics since 1817, when the first cholera pandemic began, spreading to Asia, the Middle East and part of Africa via Asia. All subsequent pandemics have originated in Asia and spread to all continents including Europe. The seventh pandemic is still ongoing, having started in Indonesia in 1961 and subsequently spread to the rest of Asia (from 1962), then Africa (1970) and Latin America (1991).

Africa is currently the worst-hit continent with outbreaks in several countries and some countries now endemic. Cholera is particularly prevalent among people with insufficient access to drinking water. The disease is a public health threat and affects different populations unequally. Conflicts and mass movements of refugees provide favorable conditions for the emergence of outbreaks. Large-scale outbreaks, such as those that occurred in Haiti in late October 2010 and Yemen in 2016, highlight the threat that this disease continues to pose to public health. Although these two major outbreaks were temporarily halted, they took hold again in 2022 during the global cholera resurgence. In 2022, outbreaks were also observed in other countries, including Lebanon and Syria, that had long remained unaffected by cholera. April 2024 saw an outbreak in the French overseas department of Mayotte following an outbreak in the Comoros Islands in February 2024.

At the Institut Pasteur

The Vibrios and Cholera National Reference Center (CNR), hosted in the Institut Pasteur's Enteric Bacterial Pathogens Unit, has been tasked by the General Directorate of Health in the French Health Ministry with monitoring, confirming and reporting cases of cholera imported into France (there are around 4 or 5 each year). As in many countries, cholera is a notifiable disease in France. The CNR works with microbiologists in countries affected by cholera outbreaks and with non-governmental humanitarian organizations, and is therefore involved in monitoring the strains of Vibrio cholerae in circulation worldwide and in reporting the emergence of new variants or multiple-antibiotic-resistant strains. A genome database developed by the unit that traces the history of the seventh cholera pandemic in Africa, the Americas and Europe is a valuable tool for improving our understanding of cholera epidemiology.

The Institut Pasteur is a member of WHO's Global Task Force on Cholera Control (GTFCC), a network of over 50 organizations that has adopted a comprehensive multi-sector approach, bringing together multiple partners working to tackle cholera. The Institut Pasteur also leads a Surveillance Working Group, which has published various technical notes. In October 2017, 35 GTFCC partners, including the Institut Pasteur, made an unprecedented commitment to fight cholera by implementing a Global Roadmap (Declaration on Ending Cholera) designed to reduce cholera deaths by 90% by 2030.

January 2025