In 2017, vaccinology expert Frédéric Tangy was recognized by the Institut Pasteur for his work on the Measles Platform and was elected as a member of the US National Academy of Inventors. As the Institut Pasteur enters its 130th year – it will be celebrating its 130th anniversary on November 14, 2018 – it seemed like a good opportunity to ask the scientist to tell us a little more about his research field. Read on for our interview with Frédéric Tangy, who also co-authored a recent book about vaccines.

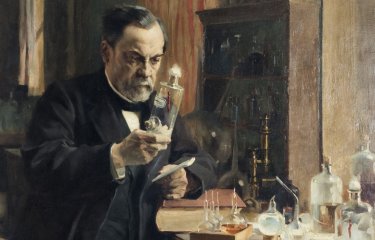

The Institut Pasteur, a member institution of the US National Academy of Inventors (NAI) since 2015, was keen to celebrate the curiosity, creativity, innovation and invention that embody its heritage. So on June 27, 2017, it honored the achievements of 14 of its inventors who have been selected as members of the NAI. The event was perfectly in tune with the pioneering spirit of Louis Pasteur and the ensuing generations of Institut Pasteur scientists. The research of these 14 scientists has given rise to several US patents involving licenses, creating a positive impact for society as a whole and for the Institut Pasteur.

Vaccines are currently the focus of wide-ranging debate in France. What is your view on the issue?

There have always been many preconceived ideas about vaccines. This is an inevitable consequence of the fact that vaccination is a preventive treatment designed to be administered to healthy people. So it can be difficult for us to grasp what good vaccines are actually doing us. These fears were already being voiced back in the era of British physician Edward Jenner and his first vaccines against smallpox. But we now know that vaccination saves millions of lives every year! In the late 1970s, smallpox was completely eradicated thanks to a campaign led by the World Health Organization combining mass vaccination and surveillance. Unfortunately, we are often quick to forget just how much vaccination has improved human health. Nowadays, the first thing we tend to see on the internet is often false claims with no objective basis in truth. Incidentally, since I began teaching vaccinology to healthcare professionals at the Institut Pasteur ten years ago, I have noticed that sometimes they themselves – with the exception of specialists such as pediatricians and infectious disease consultants – do not know enough about vaccines to be able to defend them from criticism. Medical professionals who are not in full possession of the scientific arguments can raise doubts about vaccination. So it's not hard to see why the public gets confused. People will only be reassured if they are given clear, factual information that is easy to understand. That is why my colleague Jean-Nicolas Tournier and I decided to write this book, with the aim of explaining how vaccines work and why they are so important to as many people as possible.

A huge amount of progress was made in the 20th century. In this day and age, why does it take us so long to develop a new vaccine?

The first stage in vaccine research – the purely research-based part of the process, where we start from square one and attempt to develop a vaccine candidate – is very unpredictable in terms of how long it will take. It can go relatively quickly (one or two years) or take a very long time, depending on the disease we are working on. For AIDS, the search for a vaccine has been under way for the past 30 years – and for malaria it has already taken 40 years! There are many reasons why these efforts can remain fruitless: pathogenic variability, difficulties in handling pathogens, evasion of immune responses, etc. When it comes to vaccines, all the easy work has already been done, and the more difficult work has still not been completed. Fundamental research is vital for the development of new solutions. The second stage, which cannot be fast-tracked, is the preclinical and clinical development of vaccine candidates. The preclinical phase lasts roughly two years. The aim is to develop an industrial process to manufacture the vaccine candidate and to demonstrate a lack of toxicity. It is only at this point that clinical trials in humans can be launched. The length of these trials depends on the epidemiology of the disease. Phase I assesses non-toxicity and tolerance to the vaccine in 10 to 30 volunteers. It can take one or two years. Phase II then assesses the immunogenicity of the vaccine in 100 to 300 volunteers and confirms tolerance. Finally, phase III assesses the efficacy of the vaccine in thousands or tens of thousands of people. This takes several years. Meanwhile, an industrial process for large-scale production of the vaccine must be developed.

You are one of the coordinators of the Institut Pasteur's Major Federating Program on Vaccinology. What are the aims of this program?

The program was set up to coordinate and structure the Institut Pasteur's vaccine research activities and to facilitate the transfer of this research to medical applications. Several research projects have already been launched, both in fundamental research and also further downstream to promote the industrial development of vaccine candidates for diseases such as malaria, influenza and plague. This program is not only a springboard for launching new projects; it also helps foster dialog between scientists. Groups that previously had nothing to do with vaccine research are now getting involved. New ideas are emerging – it's very exciting.

In your laboratory, you have adopted an original approach with the "measles vector", which recently earned you an award from the Institut Pasteur. How exactly does this work?

We use the measles vaccine as a vehicle. Picture the measles vaccine virus as a small car. In the trunk we store antigens for AIDS or dengue, for example, and this little car will deliver the antigens to individuals when they are vaccinated, depositing them directly in the compartments of the immune system that are able to induce a protective memory response. The measles vaccine is one of the best vaccines out there. It has been in use for more than 40 years, is distributed all over the world, and has already been administered to more than 2 billion children with total success – a 95% protection rate and no side effects. Using the measles vaccine to create vaccines for other diseases means that we get to benefit from all these advantages. We are using this method to develop vaccine candidates for AIDS, dengue, West Nile virus, yellow fever, seasonal and pandemic influenza viruses, Ebola, Lassa fever and other emerging diseases. Our most advanced project is a combined vaccine candidate for measles and chikungunya, which has already undergone a highly successful phase I clinical trial and has recently completed phase II with very positive results, in conjunction with an industrial partner. Recently, using the same strategy, we obtained a vaccine candidate for Zika virus that has proven extremely effective in experimental models. A phase I clinical trial for this vaccine has just been completed. The results of all this work are currently being analyzed but they are very promising.

Press conference in Paris, on December 22, 2018: "Les vaccins: une chance pour nos enfants!" (Vaccines, a chance for our children!)

The obligation to vaccinate in France (11 vaccines are now mandatory for children; as compared to three previously) came into effect on January 1, 2018. A press conference was organized on December 22, 2017, in Paris, under the auspices of the Paris Descartes University, in partnership with the Institut Pasteur, Inserm and AP-HP (Assistance Publique – Hôpitaux de Paris). A series of speeches were proposed around the main topics under debate.

Read the press release (in french)

Les vaccins pour les nuls (Vaccines for Dummies), published by First

* Frédéric Tangy, CNRS Research Director, Head of the Viral Genomics and Vaccination Unit at the Institut Pasteur.

* *Jean-Nicolas Tournier, Head of the Department of Infectious Diseases in the Anti-Infectious Biotherapy and Immunity Unit at the French Armed Forces Biomedical Research Institute.

Les vaccins pour les nuls (Vaccines for Dummies). Frédéric Tangy and Jean-Nicolas Tournier. Published by First. "Poche pour les Nuls" (Paperbacks for Dummies) collection. 304 pages, format 13cm x 19cm. Published on October 19, 2017.