During a wave of expansion that began 4,000 to 5,000 years ago, Bantu-speaking populations – today some 310 million people – gradually left their original homeland of West-Central Africa and traveled to the eastern and southern regions of the continent. Using data from a vast genomic analysis of more than 2,000 samples taken from individuals in 57 populations throughout Sub-Saharan Africa, scientists from the Institut Pasteur and the CNRS, together with a broad international consortium, have retraced the migratory routes of these populations, previously a source of debate. Their research reveals that the admixture that occurred as a result of successive encounters with local populations enabled the Bantus to acquire genetic mutations that helped them adapt to their new environments. Finally, by analyzing the genomes of more than 5,000 African-Americans, the scientists have identified the genetic origins of African populations deported as slaves, and confirmed that the Bight of Benin and West-Central Africa were the main ports used for the slave trade to North America. This research was published on May 5 in the journal Science.

Some 4,000 to 5,000 years ago, the emergence of farming marked a major turning point in African history. Mastering this new skill enabled Bantu speakers, previously hunter-gatherers living in the region between Cameroon and Nigeria, to gradually leave their homeland and spread to new areas. This was the start of a millennia-long journey that resulted in these populations settling throughout Sub-Saharan Africa.

Yet question marks have always remained as to the exact migratory route taken by these peoples: while a first theory known as "early split" claimed that the Bantu populations immediately divided into two groups on leaving their homeland, one heading east and one south, the "late split" theory suggests that Bantu speakers actually began by traversing the equatorial forest (today part of Gabon), before dividing into two migration waves, one continuing south and the other to East Africa.

Using genomic data from 2,000 individuals from 57 populations throughout Sub-Saharan Africa, a research team from the Institut Pasteur and the CNRS,[1] led by CNRS scientists Etienne Patin and Lluis Quintana-Murci in close collaboration with several African,[2] European[3] and American[4] institutions, have now shed new light on the question. The scientists' research revealed that populations of Bantu speakers from eastern and southern Africa are genetically more similar to populations based south of the equatorial forest than those to the north. These data therefore clearly support the "late split" theory, suggesting that the Bantu first crossed the equatorial forest before branching off into two groups following migratory routes towards eastern and southern Sub-Saharan Africa, where they came into contact with autochtonous populations inhabiting these regions.

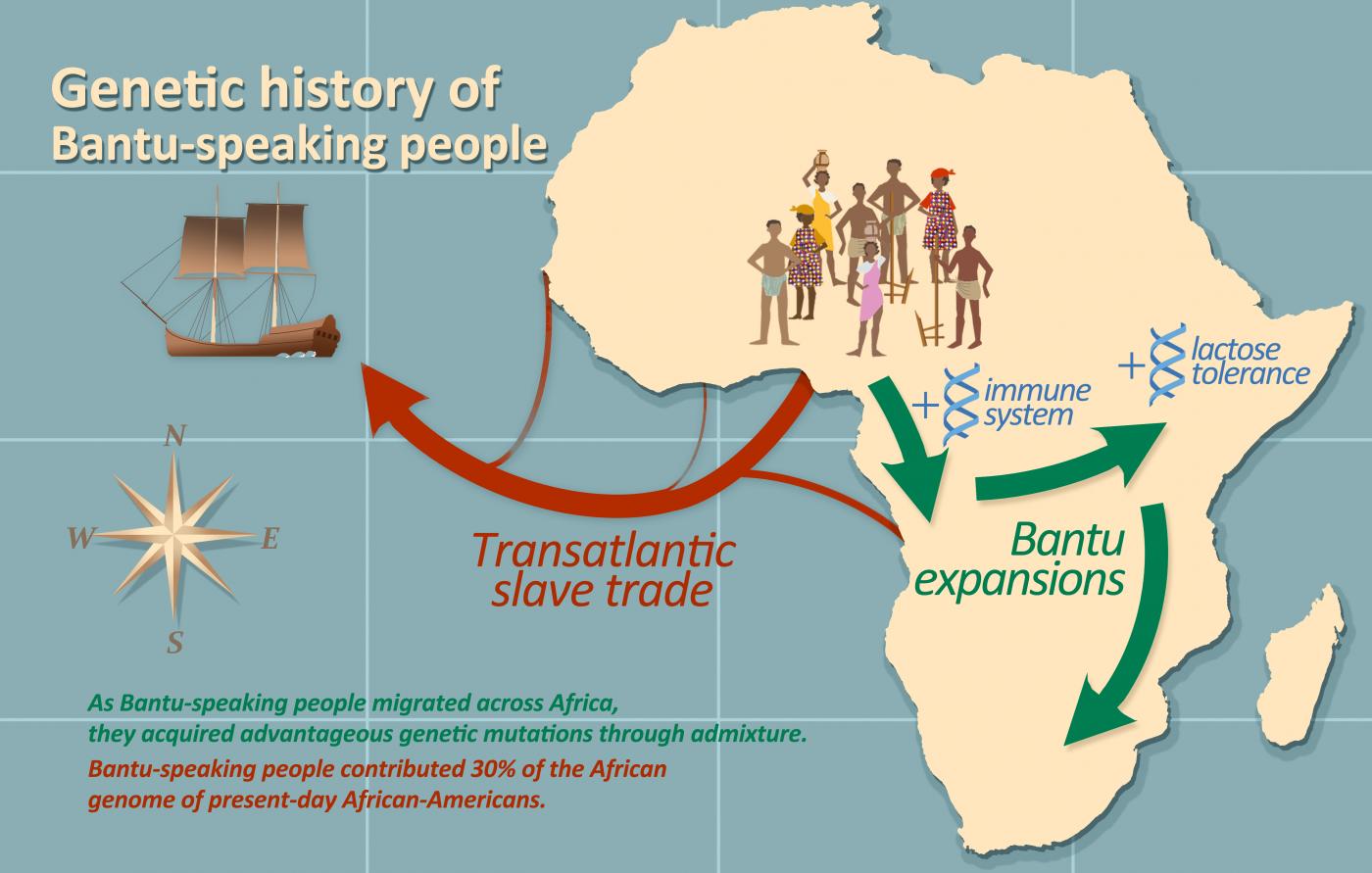

The scientists then explored the admixture of Bantu speakers with the local populations they came into contact with. Their research demonstrates that over the past millennium, the Bantus admixed with pygmy populations from West-Central Africa, Afro-Asiatic-speaking populations from East Africa and San populations from South Africa. Surprisingly, these successive admixture events appear to have been beneficial for the Bantu peoples, conferring advantageous genetic mutations that helped them adapt to their new environments. From the admixture with pygmies, for example, Bantu peoples acquired a new form of the HLA system, which helps trigger immune response to infection. Another compelling example indicates that when the Bantus arrived in eastern Sub-Saharan Africa, the local populations passed on a variability associated with the gene that codes for lactase, which enables individuals to continue digesting milk in adulthood.

"Our research resolves the migratory routes taken by Bantu peoples and shows that their admixture with local populations was beneficial for their adaptation to the environment, especially in terms of immunity," explains Lluis Quintana-Murci, who coordinated the study. "While we were already familiar with cases showing the acquisition of genetic advantages between species[5], it is virtually the first time that this concept has been demonstrated within the human population."

The final aspect explored during this vast study was how one of the most painful periods in African history, the transatlantic slave trade, affected the genetic history of the Bantu peoples. We know that the genomes of African-Americans living on the North American continent today are 75-80% of African ancestry. To trace the genetic origins of that portion of their genome more precisely, the scientists have compared the genomes of nearly 5,000 African-Americans from across the United States with those of African populations currently living in the former slave ports. This enabled them to break down the contributions of each of these slave trade regions. They found that nearly 50% of the genome of African-Americans is from the ports located in the Bight of Benin. The other major contribution, almost 30%, is from West-Central Africa (Gabon and Angola), emphasizing the heavy toll the slave trade took on these populations. Lastly, 13% comes from the former port of Senegambia (the basin of the Senegal and Gambia rivers) and 7% from the Windward Coast (Ivory Coast).

This vast genetic map of Sub-Saharan Africa provides a striking illustration of how genomics has contributed to the history of our species. It represents a powerful tool that, in conjunction with new pan-genomic approaches, can be used to reconstruct the history of our migrations and admixtures, and to identify the evolutionary mechanisms that have enabled us to adapt genetically to environmental pressures, including those exerted by infectious agents.

[1] Human Evolutionary Genetics Unit, Institut Pasteur/CNRS

[2] Omar Bongo University, Gabon, and CERPAGE/IRCB, Benin

[3] French Museum of Natural History, French Research Institute for Development (IRD), Paris-Descartes University, French Institute for Demographic Studies (INED), Paris-Diderot University, Paul Sabatier University – Toulouse III, Lumière Lyon 2 University; United Kingdom: University of Reading; and Portugal: Universidade do Porto

[4] USA: University of Missouri, Pennsylvania State University, Stanford University; Canada: University of Montreal

[5] See our press release: Africans and Europeans have genetically different immune systems... and Neanderthals had something to do with it

Source

Dispersals and genetic adaptation of Bantu-speaking populations in Africa and North America, Science, May 5, 2017.

Etienne Patin (1,2,3), Marie Lopez (1,2,3), Rebecca Grollemund (4,5), Paul Verdu (6), Christine Harmant (1,2,3), Hélène Quach (1,2,3), Guillaume Laval (1,2,3), George H. Perry (7), Luis B. Barreiro (8), Alain Froment (9), Evelyne Heyer (6), Achille Massougbodji (10,11), Cesar Fortes-Lima (6,12), Florence Migot-Nabias (13,14), Gil Bellis (15), Jean-Michel Dugoujon (12), Joana B. Pereira (16,17), Verónica Fernandes (16,17), Luisa Pereira (16,17,18), Lolke Van der Veen (19), Patrick Mouguiama-Daouda (19,22), Carlos D. Bustamante (20,21), Jean-Marie Hombert (19) Lluís Quintana-Murci (1,2,3)

1) Human Evolutionary Genetics, Institut Pasteur, 75015 Paris, France.

2) French National Center for Scientific Research URA3012, 75015 Paris, France.

3) Center of Bioinformatics, Biostatistics, and Integrative Biology, Institut Pasteur, 75015 Paris, France.

4) Evolutionary Biology Group, School of Biological Sciences, University of Reading, Reading RG6 6BX, England.

5) Departments of English and Anthropology, University of Missouri, Columbia, Missouri, MO 65211, USA.

6) French National Center for Scientific Research UMR7206, French Museum of Natural History, Paris-Diderot University, Sorbonne Paris Cité, 75016 Paris, France.

7) Departments of Anthropology and Biology, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802, USA.

8) University of Montreal, Sainte-Justine University Hospital Research Center, H3T 1C5 Montreal, Canada.

9) French Research Institute for Development, UMR 208, French Museum of Natural History, 75005 Paris, France.

10) Research Center on Malaria Associated with Pregnancy and Childhood (CERPAGE), Cotonou, Benin.

11) Benin Clinical Research Institute (IRCB), 01 BP 188 Cotonou, Benin.

12) Molecular Anthropology and Synthetic Imaging, French National Center for Scientific Research UMR 5288/Paul Sabatier University – Toulouse 3, 31073 Toulouse Cedex 3, France.

13) French Research Institute for Development, UMR 216, Tropical Infections in Mother and Child, 75006 Paris, France.

14) COMUE Sorbonne Paris Cité, Faculty of Pharmacy, Paris-Descartes University, 75006 Paris, France.

15) French Institute for Demographic Studies, 75020 Paris, France.

16) Instituto de Investigação e Inovação em Saúde (i3S), Universidade do Porto, Porto 4200-135, Portugal.

17) Instituto de Patologia e Imunologia Molecular da Universidade do Porto (IPATIMUP), Porto 4200-465, Portugal.

18) Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade do Porto, Porto 4200-319, Portugal.

19) French National Center for Scientific Research UMR 5596, Dynamics of Language, Lumière-Lyon 2 University, 69007 Lyon, France.

20) Department of Genetics, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305, USA.

21) Department of Biomedical Data Science, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305, USA.

22) Language, Culture and Cognition Laboratory (LCC), Omar Bongo University, BP 13131 Libreville, Gabon.