Although rabies control has progressed considerably since Louis Pasteur first trialed his vaccine, the disease continues to kill thousands of people who do not have access to treatment. Scientists have traced the evolution of the disease worldwide over different eras in a bid to improve our understanding of and preparedness for emerging infectious diseases.

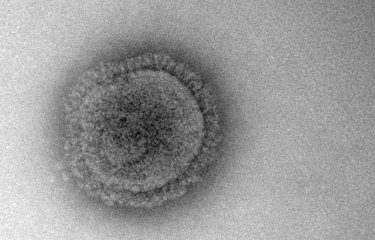

In 1885, Louis Pasteur successfully performed the first rabies vaccination on Joseph Meister, a 9-year-old shepherd from Alsace. A century and a half later, although millions of lives have been saved, rabies unfortunately continues to have a devastating impact in some Asian and African countries. In a study published in the journal Nature Communications, a team of scientists set themselves the daunting task of tracing the evolution of the rabies virus in different world regions and different eras, from the late Middle Ages to the present day.

Thousands of DNA sequences analyzed using computational biology

"Scientists can examine viral genomes to understand where they come from and how they spread. This is not an easy task, especially for ancient diseases for which we have incomplete genetic information," explains Andrew Holtz, a scientist in the Institut Pasteur's Lyssavirus Epidemiology and Neuropathology Unit and first author of the study. The scientists analyzed thousands of DNA sequences from older and newer strains of the rabies virus with known provenance. "In some cases the sequences were incomplete, but we were able to reconstruct them by comparing them with the reference genome, like when we try to piece together a puzzle using the picture," explains Anna Zhukova, a scientist in the Institut Pasteur's Bioinformatics and Biostatistics Hub and last author of the study.

Rapid expansion of rabies from the 14th century onwards

Random mutations and environmental effects meant that every sequence analyzed had slight differences – and these were used by the scientists to trace the evolutionary and geographic history of rabies. "Our method revealed that the current strain of the virus emerged between 1301 and 1403. By estimating dates and means of introduction in each region, we were able to trace the expansion of rabies at global level. We also revealed the potential impact of European colonization, as well as the broader role of humans in the spread of the disease via colonial networks and trade, for example," describes Andrew Holtz.

Understanding the spread of rabies to improve prevention and control

The scientists believe that this method of analysis could help shed light on the way in which diseases spread and evolve in different geographical areas, creating new possibilities to save lives. "By understanding how viruses spread, we can improve our preparedness and prevent future outbreaks. Knowledge of historical transmission patterns of rabies, for example, could help us develop more precise control strategies. This is particularly important if a virus acts differently from one region to the next," explain the scientists. This research will also pave the way for similar research on other viruses that makes use of vast quantities of previously untapped genetic data.

This study comes under the Emerging Infectious Diseases priority scientific area in the Institut Pasteur's 2019-2023 Strategic Plan.

Source

Integrating full and partial genome sequences to decipher the global spread of canine rabies virus, Nature Communications, July 17, 2023