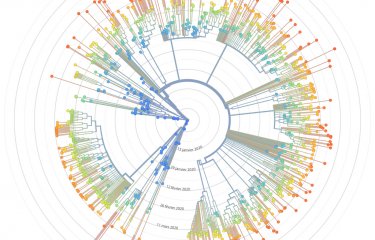

The ComCor study is conducted by the Institut Pasteur in partnership with the French National Health Insurance Fund (CNAM), Ipsos and Santé publique France.

Intermediate analysis, on March 1, 2021

The ComCor study, which currently covers the period from October 1, 2020 to January 31, 2021, includes 77,208 participants with acute SARS-CoV-2 infection, excluding healthcare workers (8.2% of those contacted by email by the French National Health Insurance Fund (CNAM)). The study describes where and in what circumstances the participants have contracted recent SARS-CoV-2 infection. It also compares the behaviors of 8,702 of these cases with that of 4,351 control subjects identified by Ipsos and matched by age, sex, place and date.

An analysis of the first four months of the study reveals the following points:

- Circumstances of infection

45% of infected individuals could identify the person considered to be the source of infection, 18% suspected that they had been infected at a specific event but could not identify the person who was the source of infection, and 37% did not know how they had been infected.

In cases in which the person considered to be the source of infection was known, it was most often someone within the household (42%), followed by someone outside the household but within the extended family (21%), someone in the workplace (15%), a friend (11%) or none of the above (11%). Private gatherings with extended family and friends and shared office spaces were the most strongly identified circumstances in which people contracted the virus. Meals, both with friends and family and in the workplace, were the most frequently reported occasions in which the virus had been contracted. It is worth noting that the additional risk associated with private gatherings fell between October and January, probably because the participants in these gatherings were managing risks more effectively.

Far too often (37% of cases when the virus was contracted outside the home), the person considered to be the source of infection was symptomatic at the moment when he/she transmitted the virus. This was particularly true in the workplace (46% of cases).

An analysis of more than 10,000 incidences of contacts outside the home that led to infection reveals that 80% took place indoors with the windows shut, 15% took place indoors with the windows open, and 5% took place outside.

- Self-isolation

Patients self-isolated from people living outside their household, but they increasingly waited to receive their test result before self-isolating, rather than self-isolating as soon as they began to experience symptoms. Nonetheless, the average time between the emergence of symptoms and the start of self-isolation fell from 1.7 days in October to 1.3 days in January, probably because people were able to access testing sooner in January than in October.

- Schooling

Within the household, having a child at school represented an additional risk of infection for adults, especially children looked after by a childminder (+39%) and those attending middle school (+27%) and high school (+29%). There was one exception, however: having a child at primary school has thus far not been associated with an additional risk of infection for adults living in the same household. But since January there has been an increase in cases of children under the age of 11 infecting adults in their household.

- Workplace

The relationship between qualifications and the risk of infection follows a parabolic curve: high-school leavers with up to four years of higher education are less at risk of infection compared with those with no high school diploma and those with five years of higher education.

The occupational categories most at risk, in ascending order of additional risk, are public-sector managerial staff, private-sector engineers and technical staff in managerial roles, private-sector administrative and sales staff in managerial roles, managers of companies with ten or more employees, intermediate health and social professionals, and drivers.

The occupational categories least at risk, in descending order of risk, are public-sector civilian employees and service staff, private-sector administrative staff, retired employees, public-sector administrative staff in intermediate roles, personal service workers, police officers and military personnel, primary and nursery school teachers, private-sector administrative and sales staff in intermediate roles, secondary school teachers and professors, scientific professionals, and farmers.

Other occupational categories are considered as being at "medium" risk of infection: trades- and craftspeople and skilled manual workers, retailers and related professionals, self-employed professionals, those working in IT, arts and entertainment, technicians, foremen and supervisors, retail employees, qualified industrial workers, students, unemployed people and the non-working population.

Public transport was not associated with an additional risk of infection, but car sharing was (+58%).

Working from home provided protection (-24% for partial remote working, -30% for full remote working compared with people carrying out the same job in an office).

- Public spaces

Classes in lecture halls or classrooms for continuing education, outdoor sport, and attendance of places of worship, shops and hairdressing salons were not associated with an additional risk of infection.

Attendance of places of worship was not associated with an additional risk of infection during the period in which they were open (October). The risk has not been able to be re-assessed since they were closed in November.

Attendance of indoor gyms was associated with an additional risk on the borderline of statistical significance during the period in which they were open (October). The risk has not been able to be re-assessed since they were closed in November.

Attendance of bars and restaurants was associated with an additional risk of infection during the period in which they were open (October). The risk has not been able to be re-assessed since they were closed in November.

Travel abroad was associated with an additional risk of infection (+53%).

These results are in line with data in the international literature, especially the studies by Fisher (MMWR, 2020) and Chang (Nature, 2021) and the very recent US cohort study by Nash (medRxiv, 2021)[1]. It also appears that the vast majority of clusters and well-characterized incidences of transmission were identified in indoor spaces rather than outdoors. (Weed & Foad, medRxiv, 2020; Cevik M, CID, 2020; Bulfone, JID, 2021)[2]

The following recommendations can be made based on the interpretation of these results:

- Continued effective communication about the risks associated with gatherings, especially in indoor spaces with no or poor ventilation and in the absence of hygiene and distancing measures, is crucial. Such gatherings appear to be the main sources of transmission of the virus.

- Emphasis needs to be placed on the importance of wearing a mask, complying with other hygiene and distancing measures and self-isolating immediately as soon as symptoms arise, rather than waiting for test results. People are most contagious within five days of the emergence of symptoms. It is also important to self-isolate from other people in the same household. The French National Health Insurance Fund (CNAM) offers various services to help people make arrangements if their circumstances make self-isolation difficult. It is essential not to go to work if experiencing symptoms.

- With regard to schools, having a child at middle or high school represents the most significant additional risk for adults. When it comes to small children, the additional risk for adults seems to be greater if their children are looked after by a childminder rather than going to a daycare center.

- Occupational categories that involve working in closed spaces (drivers) and frequent contact with other people seem to be most at risk. In working environments, it is important to keep workspaces adequately ventilated and to take protective measures when coming into contact with other people, especially during physical meetings and in shared offices and eating spaces. People should work from home where possible.

- There is no additional risk observed in public transport, probably because hygiene and distancing measures can be complied with, but car sharing represented a significant and stable risk of transmission throughout the period under study.

- Attendance of public spaces where compliance with hygiene and distancing measures is possible (shops, classrooms, lecture halls, places of worship and hairdressing salons) was not associated with an additional risk of infection in the study.

- Outdoor sport may be recommended as long as physical distance is maintained.

Please note that all these results may be called into question with the arrival of the British, South African and Brazilian variants in France. The British variant is approximately 50% more transmissible than strains that circulated predominantly in 2020. Transmission mechanisms seem to be the same, but the variant is more contagious and the length of time during which the virus is shed by infected individuals could be longer. Our European colleagues are reporting outbreaks in daycare centers, and in nursery and primary schools that had not previously been reported, and it is impossible to know whether this is a result of improved monitoring in schools, visible circulation because these places are often the last to remain open in the event of active circulation of the virus in the community, or a particular tropism of the virus that increases infectivity in children. If the increased infectivity of the British variant means that the minimum infectious dose is lower, it is possible that transmission mechanisms that were previously ineffective in children are now effective with the arrival of these more contagious variants.

[1] Fisher KA, Tenforde MW, Feldstein LR, et al. Community and Close Contact Exposures Associated with COVID-19 Among Symptomatic Adults ≥18 Years in 11 Outpatient Health Care Facilities - United States, July 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:1258–64.

Chang S, Pierson E, Koh PW, et al. Mobility network models of COVID-19 explain inequities and inform reopening. Nature 2021; 589:82-87.

Nash D, Rane M, Chang M, et al. Recent SARS-CoV-2 seroconversion in a national community-based prospective cohort of U.S. adults. medRxiv, 2021; https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.12.21251659.

[2] Bulfone TC, et al. Outdoor transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and other respiratory viruses: a systematic review. J Infect Dis. 2021;223:550-561.

Weed M & Foad A. Rapid scoping review of evidence of outdoor transmission of Covid-19, 2020, medRxiv https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.09.04.20188417v2

Cevik M, Marcus JL, Buckee C, Smith TC, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Transmission Dynamics Should Inform Policy, Clin Infect Dis, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa1442

Source

Study examining the sociodemographic, behavioral and practical factors associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection (ComCor). Read the full study here (in French).

Institut Pasteur :

Unité d’épidémiologie des maladies émergentes : Simon Galmiche, Tiffany Charmet, Laura Schaeffer, Rebecca Grant, Arnaud Fontanet

Unité de modélisation des maladies infectieuses : Juliette Paireau, Simon Cauchemez

Centre pour la recherche translationnelle : Olivia Chény, Cassandre Von Platen

Caisse Nationale d’Assurance Maladie :

Alexandra Maurizot, Carole Blanc, Annika Dinis, Sophie Martin

Institut IPSOS : Faïza Omar, Christophe David

Sorbonne Université, Inserm, IPLESP, Hôpital Saint-Antoine, APHP : Fabrice Carrat

Santé Publique France : Alexandra Septfons, Alexandra Mailles, Daniel Levy-Bruhl

Projet financé par Reacting (Agence ANRS-MIE) et l’Institut Pasteur