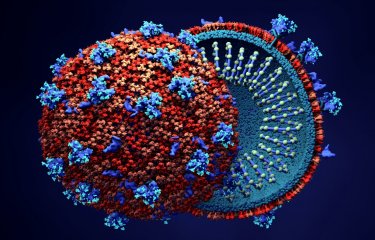

Current HIV treatments efficiently block viral multiplication but cannot cure infection as they do not target HIV infected cells. HIV cure or profound HIV remission have been described in three persons with HIV who underwent allogeneic stem cell transplantation to treat severe blood cancers. However, this procedure has not eradicated the virus in other persons. A work led by scientists from the University Medical Center Hamburg and the Institut Pasteur in the context of the ICISTEM international consortium has analyzed the evolution of the immune system in 16 persons with HIV after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. The scientists identified a phase of strong activation of the immune system occurring after the transplant which may provide a window of vulnerability for the reseeding of the HIV reservoir in the expanding donor cells. Their findings are published in the journal Science Translational Medicine on May 6, 2020.

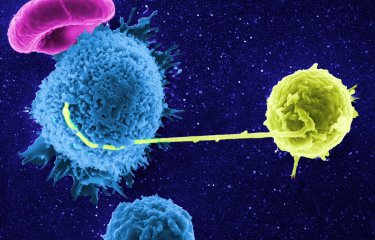

The antiretroviral treatment used today is not able to eliminate the virus from the body, which remains nested in immune cells, in particular CD4 cells, from where the virus starts multiplying again and infecting new cells if the antiviral treatment is discontinued. There is currently no strategy that can target and selectively eliminate the infected cells from the organism. Allogeneic stem cell transplant is used to treat patients with life-threatening blood cancers, such as leukemia or lymphoma, or severe disorders of the immune system. During these transplants, most of the immune cells from these patients are eliminated by ablation techniques. Stem cells from a healthy donor are then used to replace damaged bone marrow in the patients in order to restore their immune system. Some persons with HIV also need to undergo allogeneic stem cell transplantion to resolve different types of hematological cancers. Such interventions have been accompanied by spectacular decreases in the number of HIV-infected cells, which became undetectable in almost all cases. Moreover, in three individuals the virus remains undetectable despite interruption of antiretroviral treatment, indicating that HIV cure or at least deep HIV remission has been achieved in these persons. In all three cases, the patients were transplanted with stem cells from donors who carried a mutation (CCR5D32) that impairs the expression on the cell surface of one of the main HIV entry receptors, rendering them resistant to some HIV strains. In contrast, viral replication started again in several other instances in which persons with HIV who had received allogeneic stem transplant discontinued their antiretroviral treatment.

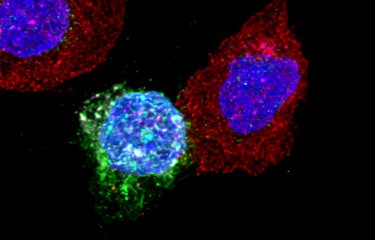

The ICISTEM study (www.icistem.org) compiles exceptional cases of persons with HIV who need allogeneic stem cell transplant. The aim is to perform comprehensive studies on the HIV dynamics, viral reservoir and immune responses after the transplant and identify the factors leading to HIV cure/remission or resurgence in these patients. A study led by scientists from the HIV, inflammation and persistence unit at the Institut Pasteur and from the Infectious Diseases Unit at University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf has analyzed the evolution of the T cell compartment after the transplantation in 16 persons with HIV and antiretroviral treatment, including 5 patients who received cells with the CCR5Δ32 mutation. They found that the initial weeks after the transplantation, when cells from both the donor and the patient still coexisted, were characterized by strong activation of CD4 cells. Therefore, although only a few original cells from the patients remained during this period, their activation may promote the reactivation of HIV provirus and the reseeding of infection in expanding CD4 cells from donors, which are perfect HIV targets if the infection is not avoided by efficient antiretroviral treatments or genetic barriers (such as the CCR5D32 mutation for viruses using such receptor).

The researchers also observed that new CD8 responses directed against HIV proteins developed from donor cells following this period. This indicated that during their expansion the cells from the donors where in contact with HIV factors and were trained to react against them, confirming the existence of a “window of vulnerability” during which infection of cells from donor origin may occur. However, these new CD8 responses against HIV were weak and of poor quality when compared to responses that were developed in the same patients against other chronic infections such as cytomegalovirus, known to reactivate during the transplantation. In some cases, HIV responses persisted at relatively high frequencies for many years after the transplantation, which might reveal HIV persistence in hidden anatomical reservoirs in these individuals, as confirmed in at least one of the cases studied who experienced viral rebound after interruption of antiretroviral treatment.

Together with previous results from the ICISTEM consortium, these novel results reveal a vulnerability that may explain why allogeneic stem cell transplant, despite drastically decreasing the number of infected cells in the organism, may not totally eradicate the virus from the body. A few infected cells may remain unnoticed in non-accessible organs and promote viral rebound that would not be controlled by the relatively inefficient immune responses already present. Additional immunotherapies or interventions aimed to reinforce control may be needed to achieve remission in persons with HIV after allogeneic stem cell transplant who did not receive cells with intrinsic resistance to infection.

Source

Vulnerability to reservoir reseeding due to high immune activation after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in individuals with HIV-1, Science Translational Medicine, May 6, 2020

Johanna M. Eberhard1,2, Mathieu Angin3, Caroline Passaes3, Maria Salgado4, Valerie Monceaux3, Elena Knops5, Guido Kobbe6, Björn Jensen7, Maximilian Christopeit8, Nicolaus Kröger8, Linos Vandekerckhove9, Jon Badiola10, Alessandra Bandera11, Kavita Raj12, Jan van Lunzen1,13, Gero Hütter14, Jürgen H.E. Kuball15, Carolina Martinez-Laperche16, Pascual Balsalobre16, Mi Kwon16, José L. Díez-Martín16, Monique Nijhuis15, Annemarie Wensing15, Javier Martinez-Picado4,17,18, Julian Schulze zur Wiesch1,2, # and Asier Sáez-Cirión3, #

1I-Department of Medicine, Infectious Diseases Unit, University Medical Center HamburgEppendorf, 20246 Hamburg, Germany.2DZIF Partner Site (German Center for Infection Research), Hamburg - Lübeck - Borstel - Riems, Germany.

3Institut Pasteur, HIV, Inflammation and Persistence, 75015 Paris, France.

4AIDS Research Institute IrsiCaixa, 08916 Badalona, Spain.

5Institute of Virology, University of Cologne, 50935 Cologne, Germany.

6Department of Haematology, Oncology and Clinical Immunology, University Hospital Düsseldorf, 40225 Düsseldorf, Germany.

7Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Infectious Diseases, University Hospital Düsseldorf, 40225 Düsseldorf, Germany.

8Department of Stem Cell Transplantation, University Medical Center HamburgEppendorf, 20246 Hamburg, Germany.

9HIV Cure Research Center, Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Ghent University and Ghent University Hospital, B-9000 Ghent, Belgium.

10Hematology Department, Virgen de las Nieves University Hospital, 18014 Granada, Spain.

11San Gerardo Hospital, University of Milano-Bicocca, 20900 Monza, Italy.

12Department of Haematology, King's College Hospital, London SE5 9RS, UK.

13ViiV Healthcare, Brentford, Middlesex TW8 9GS, United Kingdom.

14Cellex, 01307D resden, Germany.

15University Medical Center Utrecht, 3584 CX Utrecht, Netherlands.

16Hospital Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Instituto de Investigación Sanitarias Gregorio Marañón, Universidad Complutense, 28007 Madrid, Spain.

17UVic-UCC, 08500 Vic, Spain.

18ICREA, 08010 Barcelona, Spain.

#Equal contributors