With outbreaks in Angola in 2015 and Brazil in 2016, and cases detected in French Guiana in 2017 and even recently in Asia, where the virus had never previously been witnessed, yellow fever – a sometimes fatal mosquito-borne disease – has once again become a global public health problem. After major outbreaks between the 17th and 19th centuries, it never disappeared and has continued to be rife in some world regions. WHO even believes that the impact of yellow fever is underestimated, suggesting that the real number of cases is 10 to 250 times higher than those currently notified.

Referred to as "yellow" fever because of the jaundice it causes in some patients, this viral disease was first described in the mid-16th century in Mexico. Although it is endemic in Africa and South and Central America, there is an effective, harmless vaccine, which offers lifelong protection and can be administered with a single injection. Yellow fever is also an imported disease: unvaccinated tourists can become infected in endemic regions and develop the disease when they return from their travels.

The disease is currently re-emerging in some African and South American countries with poor vaccine coverage. There have also been recent reports of yellow fever cases for the first time in China.

WHO emphasizes that the main weapons in the fight against yellow fever are "preventive vaccination, an expanded global vaccine stockpile for outbreak response and support for greater preparedness in the most at-risk countries." These defense strategies continue to be extensively investigated by scientists at the Institut Pasteur in Paris and in the Institut Pasteur International Network.

What is yellow fever?

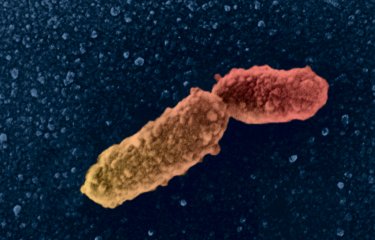

Yellow fever is caused by an arbovirus – a virus transmitted by an insect vector. The disease is transmitted to humans via bites from mosquitoes in the genera Aedes (read "The Geopolitics of the Mosquito" report) and Haemagogus. Following a one-week incubation period, yellow fever typically begins with fever, chills, muscle pain and headaches. In most cases, the symptoms disappear after 3-4 days.

But there are also more serious forms, characterized by the onset of a hemorrhagic syndrome with blackish vomit (hence the Spanish name for yellow fever, vomito negro), jaundice (which accounts for the name in English) and renal problems (albuminuria). Death then occurs in 50 to 80% of cases, after delirium, seizures and coma.

Apart from prevention by vaccination, the only way to fight the disease once it has been contracted is through rest, rehydration therapy, and drugs to lower temperature and relieve vomiting and pain.

Yellow fever in Africa and South America

Yellow fever is endemic in 47 countries in Africa and 13 countries in Latin America – and it is now reaching areas where it had previously disappeared, with a major impact on populations and sometimes also on the economy and development. In 2017, the "Arboviruses, Respiratory Infection Viruses and Hantaviruses" National Reference Center at the Institut Pasteur in French Guiana confirmed a local case of infection with yellow fever virus. The last diagnosed case of yellow fever in French Guiana dates back to 1998. Scientists confirmed the infection by serology (identification of antibodies against the yellow fever virus) and by revealing genomic material from the virus in biological samples.

Yellow fever is transmitted by various mosquito species and primarily affects monkeys in equatorial forests, making it difficult to completely eradicate the disease. It is therefore a virus that needs to be monitored closely, especially since its complexity often prevents the adoption of effective vaccine strategies (see inset below).

Yellow fever outbreak in Brazil finally elucidated

In 2016, Brazil experienced its worst yellow fever outbreak in a century. Thousands of cases were reported, and there were more than 600 fatalities. Research resulting from a recent international partnership between scientists from the Institut Pasteur, the University of Oxford and Fiocruz, published in the journal Science, shed light on the genetic makeup of the yellow fever virus and the spatial distribution of human cases in terms of age and gender.

The yellow fever virus can be transmitted in two ways: by the urban cycle and the sylvatic (jungle) cycle. In 2016, the scale of the outbreak raised fears that the virus could expand to an urban cycle, potentially spreading to megacities such as São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, where vaccine coverage is low. The vaccine is currently mainly distributed to people living on the outskirts of forests, who are considered to be at high risk of infection.

"Although all the conditions were ripe for urban transmission, the genomic and epidemiological data in our study confirmed that the virus was transmitted by the sylvatic cycle," explains Simon Cauchemez, Head of the Mathematical Modeling of Infectious Diseases Unit at the Institut Pasteur.

Analysis of cases combined with local data from the affected areas revealed that there had been low-level transmission between primates in forests during 2016, before the outbreak spread to humans in early 2017. The data also determined that in 85% of cases in primates or humans, the subjects were male and aged between 35 and 54.

"We can now reuse the same combination of techniques to improve our understanding of yellow fever transmission in other endemic areas," explains Simon Cauchemez.

Aedes aegypti female, raised at the Vectopôle de l'Institut Pasteur de la Guyane. The Aedes aegypti mosquito is a vector of dengue, chikungunya, yellow fever and zika.

© Institut Pasteur de la Guyane - Picture of Pascal Gaborit

As with all arboviruses, tackling yellow fever also involves dealing with insect vectors. "For yellow fever," confirms WHO, "vector surveillance targeting Aedes aegypti and other Aedes species will help inform where there is a risk of an urban outbreak." Scientists at the Institut Pasteur recently discovered that the yellow fever virus can also be transmitted by the tiger mosquito.

On the American continent, this mosquito, Aedes albopictus, arrived in Brazil in 1986. It is an opportunistic species that is capable of colonizing a wide variety of habitats ranging from urban areas to forests, meaning that it can serve as a link between the forest cycle and a possible urban cycle of yellow fever.

Scientists infected tiger mosquitoes orally in the laboratory to investigate the question. "From the fifth cycle onwards, the virus was finally detected in the mosquitoes' saliva, indicating that viral transmission was possible. The viral load was as high as 100 million viral particles per mosquito saliva sample," explains Anna-Bella Failloux from the Arboviruses and Insect Vectors laboratory at the Institut Pasteur.

By monitoring both insect vectors and infected animal or human populations, scientists can rapidly detect any circulating viruses so that public authorities can investigate potential threats as soon as possible. Epidemiologists examine the various risk factors of a given disease so as to predict its emergence in a population. Arnaud Fontanet, Head of the Epidemiology of Emerging Diseases Unit at the Institut Pasteur, explains more (see interview below).

The first measure to take in response to a yellow fever outbreak is to vaccinate people in at-risk areas.

How is a yellow fever outbreak detected?

In Africa, outbreaks are detected by monitoring typical yellow fever symptoms, especially high fever and jaundice. Countries in Central and West Africa where yellow fever is rife are aware of the risk of epidemics in urban areas; any cases in these regions are closely monitored and samples are sent by doctors to reference centers. These centers then study the samples, and if found to be positive, they are sent for confirmation to the Institut Pasteur in Dakar, which plays a role in regional surveillance and is also a WHO Collaborating Center for yellow fever.

Outbreak surveillance in Latin America is rather different. Since monkeys fall ill when they are infected, they can serve as a sentinel for yellow fever. This is what is known as an epizootic, an outbreak which affects animals. Monitoring these epizootics can reveal whether the yellow fever virus is active in a given region. The mosquitoes involved in spreading the virus in Latin America are not the same as those in Africa, with mosquitoes of the genus Haemogogus transmitting the disease in forest areas and Aedes albopictus (tiger mosquitoes) in intermediate regions between forests and urban areas.

What intervention measures should be introduced once an outbreak has been detected?

The first measure to take in response to an outbreak is to vaccinate people in at-risk areas. One of the major challenges with yellow fever is making sure there are enough doses of vaccine to immunize all individuals in the immediate area. We now know that it is possible to use just a fraction of the vaccine dose in the event of an outbreak, to maintain vaccine stocks.

The other important measure is vector control. One particular challenge is improving methods of tackling the Aedes aegypti vector, which we know is very hard to eliminate because it is widespread in urban areas and highly anthropophilic.

Why has yellow fever virus never reached Asia?

One of the mysteries surrounding yellow fever is its absence from the Asian continent – despite the fact that conditions there seem to be ripe. The Aedes aegypti vector, present in Asia, is capable of replicating and transmitting the virus. We also know that Asian populations can develop yellow fever because there have been imported cases. So we are none the wiser as to why the virus has not traveled to Asia. Is there an element of chance? Maybe the imported cases were not bitten by the right vector on returning to their home country. And maybe just one or two cases are not enough, and there needs to be a "critical mass" of infected cases for an outbreak to develop. It may also be that the vector is less competent in transmitting the virus, or that the population is genetically less susceptible to infection.

What is epidemiology?

Epidemiology is the study of the distribution and determinants of diseases in populations. By distribution, we mean who is ill, when and where? Epidemiology is based on disease surveillance, thanks to the efforts of networks of doctors, laboratories and hospitals, which provide data that can be used to monitor the development of a disease in a population: is it on the rise, stable or falling? Are there any outbreaks?

The other branch of epidemiology looks at the determinants of disease – in other words, their causes: are they caused by our genes, our behaviors (e.g. alcohol, tobacco, diet) or our environmental exposures (e.g. atmospheric pollution)? To carry out epidemiological research, we recruit population cohorts of thousands of individuals who are monitored over decades and in whom the link between exposure and disease is analyzed in minute detail.

What are the most recent innovations in the field of epidemiology?

Nowadays we can fine-tune our surveillance methods because we have access to larger volumes of data than with traditional networks. For example, analyzing conversations on social media using a search engine that targets keywords associated with epidemic-prone diseases can reveal areas of increased interaction that may point to potential outbreak zones.

In the United States, this tool has been used by Google during influenza outbreaks. Google was able to reproduce the epidemic curves of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta, which is responsible for monitoring outbreaks, with a fair degree of accuracy. But this approach needs to be used with caution, since one year, excessive media hype surrounding the outbreak led to a rise in social media interactions that no longer reflected the actual curves of influenza cases.

Another innovative approach for outbreak monitoring is the use of small portable sequencing devices to analyze viral strains in the field in outbreak areas. These sequences can then be cloud-shared to trace transmission chains in "real time".

You are currently holder of the newly created Public Health Chair at the Collège de France. Why do we need to provide teaching about public health in the current context?

Public health was a field that was not previously represented at the Collège de France. But public health questions – on the organization of treatment, health economics or the identification of disease determinants, for example – are highly topical issues. Huge numbers of people are interested in finding out more about the potential toxicity of products that we inhale or consume. And epidemiology is a way of providing answers, while also suggesting measures for prevention and detection.

The courses* provided in connection with this Public Health Chair will look at epidemiology as a scientific discipline, as well as pandemics as a field of application for epidemiology.

*All courses are free of charge and open to the public, with no need to sign up.

The yellow fever vaccine, guaranteed prevention

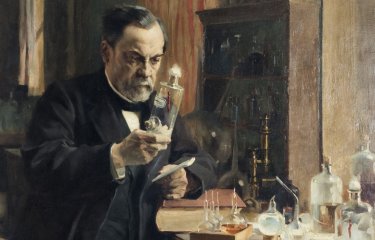

The yellow fever vaccine is the most effective means of protection against the virus. As early as 1932, a first vaccine was developed by scientists at the Institut Pasteur in Dakar, virtually eradicating epidemic yellow fever in French-speaking Africa. It has since been replaced by a new vaccine, produced in particular at the Institut Pasteur in Dakar, a laboratory with WHO accreditation to provide the vaccine for use in large-scale vaccination programs in Africa.

Prevention against yellow fever is required not only for inhabitants of the countries where the virus is found, but also for those traveling to these countries. In France, for example, the Institut Pasteur Medical Center (CMIP) offers treatment and travel vaccinations. It has extensive expertise in treating infectious and tropical diseases and in travel medicine. The Center carries out regular epidemiological surveillance so that it can provide travelers with up-to-date information, and if an outbreak occurs in a travel destination, a suitable vaccine can be recommended. "We monitor outbreaks in the field so that we can advise travelers. It's impossible to practice travel medicine without involving epidemiology," explains Paul-Henri Consigny, Director of the Institut Pasteur Medical Center. "In Brazil, there were more yellow fever cases in travelers in the first three months of 2018 than over the previous 30 years. The main reason was the low vaccine coverage among travelers to the region, since the vaccine was not compulsory but merely recommended before traveling to Brazil." Furthermore, even though Brazil is an endemic area, this mainly applies to its rural and forest regions. It is thought that tourists may have decided not to get vaccinated since they believed that they were not at risk if they only traveled to urban areas. Indeed, it was found that those individuals suffering with yellow fever after returning from Brazil had not been vaccinated.

It's impossible to practice travel medicine without involving epidemiology.

Paul-Henri ConsignyDirector of the Institut Pasteur Medical Center

The Institut Pasteur Medical Center, recognized for travel vaccinations

The Institut Pasteur Medical Center plays an important role in vaccinating travelers against yellow fever, since this vaccine is only offered at travel vaccination centers. The Center vaccinates around 20,000 people each year. It follows national and international recommendations, and is often confronted with cases of relative or absolute contraindication, such as pregnant women or patients with immune deficiency. In these cases, even if the vaccine can be administered, the Center generally decides to issue a medical waiver attesting to a contraindication to vaccination, which of course does not actually provide protection against yellow fever, or to advise individuals who have not been vaccinated against traveling to at-risk areas.

In 2013, a WHO group of experts concluded that a single dose of vaccination is sufficient to confer lifelong protection against yellow fever, a decision enshrined by WHO and implemented on July 11, 2016. Why?

- Firstly, because the yellow fever vaccine is highly immunogenic; it gives rise to neutralizing antibodies, and several studies – including one carried out at the Medical Center – have demonstrated long-term seropersistence in these antibodies, with rates of more than 85% more than 10 years after vaccination.

- Secondly, because, even though the data can be difficult to interpret, the number of yellow fever cases in vaccinated individuals remains very low.

The French High Council for Public Health (HCSP) still recommends a yellow fever booster vaccination for children vaccinated before the age of 2 and women who received a prime vaccination during pregnancy, as well as people living with HIV and immunodeficient patients, if there is no contraindication.

Yellow fever vaccine: are stocks running out?

We know that there is a shortage of yellow fever vaccine at global level. In light of this problem, vaccination trials with lower doses (in general one-fifth of the usual dose) have been carried out in endemic areas, with success. Authorities are sometimes also forced to adapt vaccination indications, though this generally involves recommendations rather than obligations. Scientists from the University of Oxford and the Institut Pasteur set out to shed light on the geographical spread of the outbreak in Angola in 2016 with the aim of optimizing the use of available vaccines. A first phase of their study involved finding out if there was a pattern to the spread of the disease, to establish whether it was possible to predict. The authors indeed determined a clear pattern: propagation of the virus grew exponentially over time and it very quickly spread around Angola's capital, Luanda. "Invasion was positively correlated with high population density," explains Simon Cauchemez. "We used this understanding of the yellow fever propagation process to infer the district-specific infection risk in the countries concerned," he adds. "We were then able to differentiate between districts with a high risk of infection and those with a lower risk."

The WHO EYE Strategy to eradicate yellow fever

The outbreak in Angola in 2016 led WHO to introduce the global Eliminating Yellow Fever Epidemics (EYE) Strategy. The aim of this long-term strategy (2017-2026) is to establish global cooperation between the countries and partners actively involved in tackling the risk of yellow fever outbreaks. The EYE strategy is based on three main principles.

- Protecting at-risk populations. Protection involves mass preventive vaccination campaigns in areas where the risks of yellow fever virus transmission are high and herd immunity is insufficient. The aim is also to reach all children by including yellow fever vaccination in routine immunization programs.

- Preventing international spread of the disease. Globalization means that people working in a number of different sectors regularly travel to endemic areas. To protect these exposed workers, consultations should be held to develop strategies that protect all at-risk individuals in this situation. Strict application of the International Health Regulations is also required – the transport industry needs to step up yellow fever vaccination controls upon entry and departure, depending on travelers’ countries of origin and destination.

- Containing outbreaks rapidly. Early detection of outbreaks is vital if they are to be tackled effectively. In all countries, yellow fever monitoring could be based on the Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response (IDSR) system. Making sure vaccines are available at all times is also crucial to stem outbreaks. Emergency stockpiles would ensure rapid, fair access to vaccines in emergency situations.

In short, responding effectively to a yellow fever outbreak requires early detection of cases, reactive vaccination, good case management, vector control and community engagement.

How to prepare for travel

Before setting off on a trip overseas, it is a good idea to find out about any applicable rules and best practices.

To protect yourself against diseases that may be severe, such as yellow fever, vaccination is vital. Before traveling abroad, a vaccination schedule should be drawn up based on two criteria:

- Administrative obligation: the measures adopted by the country to protect against an infectious risk from another country, rather than the actual risks for the traveler.

- The actual risks for travelers: these vary depending on the health situation of the country they are going to, the conditions and length of their stay and each traveler's own situation, especially their age and previous vaccinations.

When it comes to yellow fever, the vaccination schedule is straightforward: travelers need to be administered with a dose of yellow fever vaccine at least 10 days before setting off. Infants may be vaccinated from the age of 9 months.

As well as vaccinations, there are a number of other recommendations to observe before setting off on an international trip. It is important to make sure you are protected against the following risks:

- malaria;

- mosquito bites that are responsible for other types of infection such as dengue;

- envenomation, bites from dogs or other mammals;

- road accidents and falls, which are frequent causes of repatriation;

- sexually transmitted infections.

Finally, you should apply basic hygiene measures, both personal hygiene and food safety.

Bear in mind that young children, pregnant women and the elderly are more vulnerable and therefore more exposed to all these risks.

More information to prepare for travel (in French)