Urinary tract infections (UTI) are a group of infectious diseases that predominantly impact healthy adult women, although they can also cause serious disease in men. They are the second most prevalent infection after respiratory infections*. The immune response to UTI is still not well-understood, and a better understanding could help lessen the use of antibiotics for this common infection.

Normally, when a person is infected by microorganisms, such as bacteria, they develop immune memory. If the same bacteria are encountered again, the body’s immune response will be able to prevent infection before it can develop. However, in the case of urinary tract infections (UTI), about half of all people that become infected do not develop sufficient immune memory to prevent a second infection.

The role of macrophages in immune memory suppression

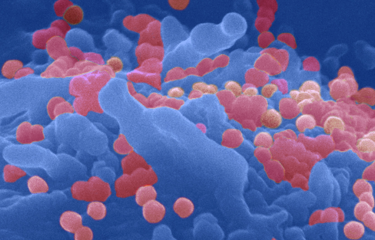

A team of researchers from the Institut Pasteur, previously found that macrophages (a type of immune cell) play a role in inhibiting the development of immune memory in the bladder. “One role of the macrophage is to ensure that different tissues in the body work normally. If an immune response is too strong, it can negatively impact the function of an organ, such as the bladder,” explains Molly Ingersoll, Head of the Mucosal Inflammation and Immunity Group at the Institut Pasteur in Paris.

A new research project to find out the mechanism behind this inhibition

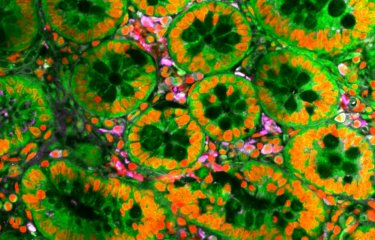

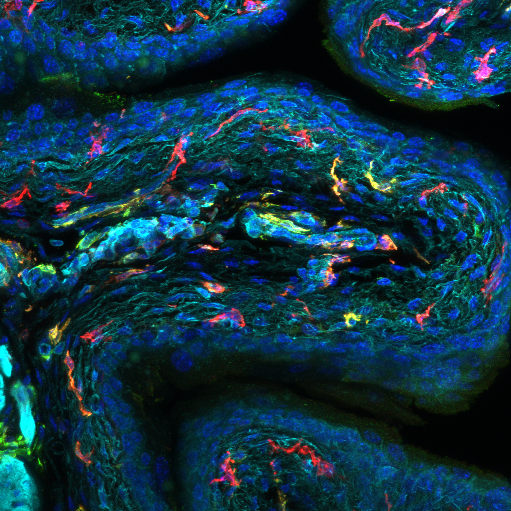

As explained in an article published in Science Advances, the team found that there are two kinds of macrophages that reside in the bladder all the time. “They are located in different parts of this organ and have different roles during infection. One macrophage dies very quickly after infection, potentially due to disruption of its niche by the bacteria. The second type of macrophage eats bacteria and then turns on proteins that inhibit the immune response.” Ingersoll explains. The team hypothesized that these actions help to limit damage to the bladder caused by the bacteria and the host immune response, to ensure that bladder is able to continue to function as a storage site for metabolic waste. Experimentally, they observed that immune memory is improved in response to a second infection when these cells were removed during UTI.

Thus, by understanding the roles of these two types of macrophages, and the specific responses they turn on, “strategies to target relevant pathways to improve the response to recurrent UTI could be developed and the use of antibiotics for this very prevalent infection could be limited,” Ingersoll says.

* Read also Demystifying immunity in the bladder

Molly Ingersoll’s Mucosal Inflammation and Immunity Group worked with the UtechS CB, UtechS PBI and Image Analysis hub, and the Computational Biology Department, at the Institut Pasteur (Paris).

This work is funded by the ANR (French National Research Agency).

Source

Functionally distinct resident macrophage subsets differentially shape responses to infection in the bladder, Science Advances, 25 november 2020

Livia Lacerda Mariano

1Department of Immunology, Institut Pasteur, 75015 Paris, France.

2INSERM U1223 Paris, France.

3Bioinformatic and Biostatistic Hub, Department of Computational Biology, Institut Pasteur,USR 3756 CNRS, Paris, France.

4Biomics Platform, Center for Technological Resources and Research (C2RT), Institut Pasteur,Paris, France.

5Aix Marseille University, CNRS, INSERM, CIML, Marseille, France.

6Macrophages and Endothelial Cells, Department of Developmental and Stem Cell Biology,CNRS UMR3738, Department of Immunology, Institut Pasteur, Paris, France