Cholera: a public health threat that still causes devastating outbreaks

Nearly a million people are currently suffering from cholera in Yemen, a worrying reminder that cholera remains a topical issue and a serious and fatal illness. Often thought of as an ancient disease, cholera is an acute intestinal infection caused by the Vibrio cholerae bacterium. Since the early 19th century, there have been seven cholera pandemics around the globe, resulting in millions of deaths. A few weeks ago scientists proved that the seventh cholera pandemic (which is currently raging in Africa, and has been since 1971) originated in Asia, as did the majority of antibiotic-resistant strains of cholera that are isolated on this continent.

There's a saying in French that describes an impossible choice as akin to "choosing between plague and cholera". This wry expression describes a no-win situation, a cruel dilemma. For many, the idea of "plague or cholera" harks back to a bygone era – few people are aware that cholera is actually still a dangerous disease that is rife in every continent.

"Cholera is an accute digestive infection caused by ingesting water or food that has been contaminated by Vibrio cholerae (cholera vibrios), bacteria from serogroups O1 or O139," explains Marie-Laure Quilici, Head of the French National Reference Center (CNR) for Vibrios and Cholera in the Enteric Bacterial Pathogens Unit led by Dr. François-Xavier Weill (based at the Institut Pasteur). The disease therefore mainly affects developing countries, where hygiene and safe water are severely lacking.

What is cholera?

Cholera is caused by ingesting water or food that has been contaminated by the Vibrio cholerae bacterium. The incubation period for the disease can range from a few hours to a few days, after which time the infected person begins to suffer from severe diarrhea and vomiting (but no fever). If left untreated, 25 to 50% of patients will die within 1 to 3 days as a result of circulatory collapse (a steep drop in blood pressure). The death rate is higher among children, elderly people and those with weak immune systems.

Treatment primarily involves replacing lost water and electrolytes. Depending on the level of dehydration, patients are rehydrated orally or by intravenous administration. Improvements can be observed after just a few hours and patients recover fully, with no lasting effects, within a few days. Antibiotic therapy is recommended by WHO only for severe dehydration.

Read the Cholera Fact Sheet

Millions of cholera cases remain unreported

There have been nearly a million cases of cholera in Yemen reported to the World Health Organization (WHO), since April 2017. The International Committee of the Red Cross has described what is happening in this country as "the world's single largest humanitarian crisis". For a single country, the sheer number of cases that occur in Yemen is staggering; the number reported there in less than a year is equivalent to the total number of cases declared in Haiti since 2010. Yemen’s annual case count also represents more than a quarter of WHO’s yearly estimate, which is between 1, 3 and 4 million cases in the world annually. "Despite the International Health Regulations, revised in 2005 to encourage countries to declare events constituting a public health emergency, cases remain under-reported worldwide," says Marie-Laure Quilici, due to under-reporting for fear of economic consequences, to often-insufficient surveillance systems, and to a lack of standardized terminology for defining a case of cholera.

Cholera – present in many parts of the world

In mainland France, cholera (a notifiable disease) remains a rare imported disease, and the number of cases is steadily falling. But cases of cholera are reported by countries in every region of the world , and is endemic in some countries in South Asia. It is also prevalent in Africa and more recently in the Americas, with the island of Hispaniola.

How does cholera spread?

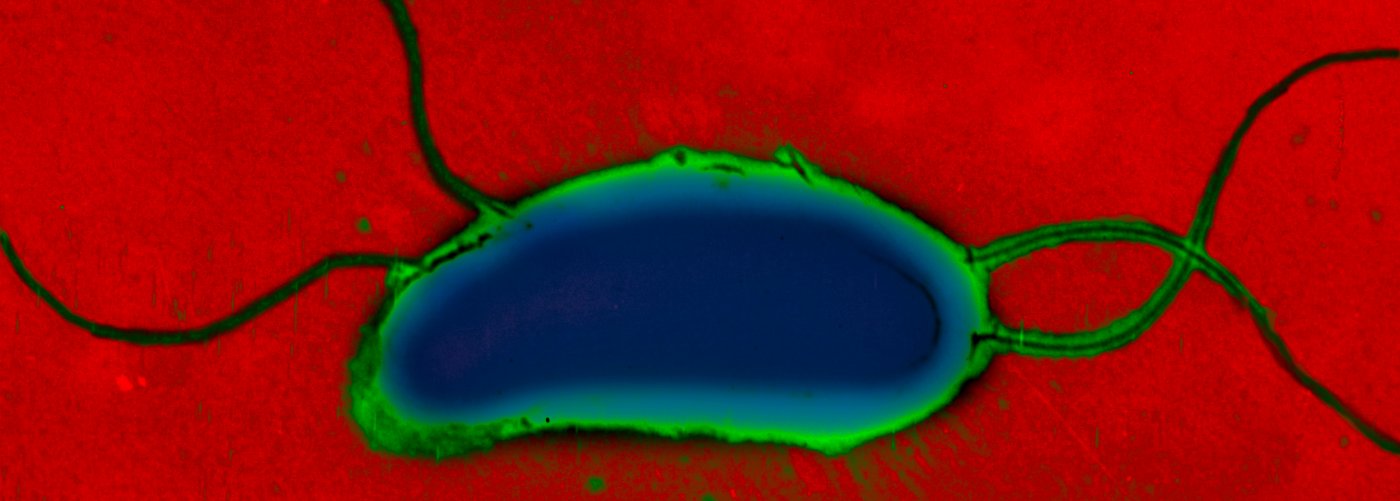

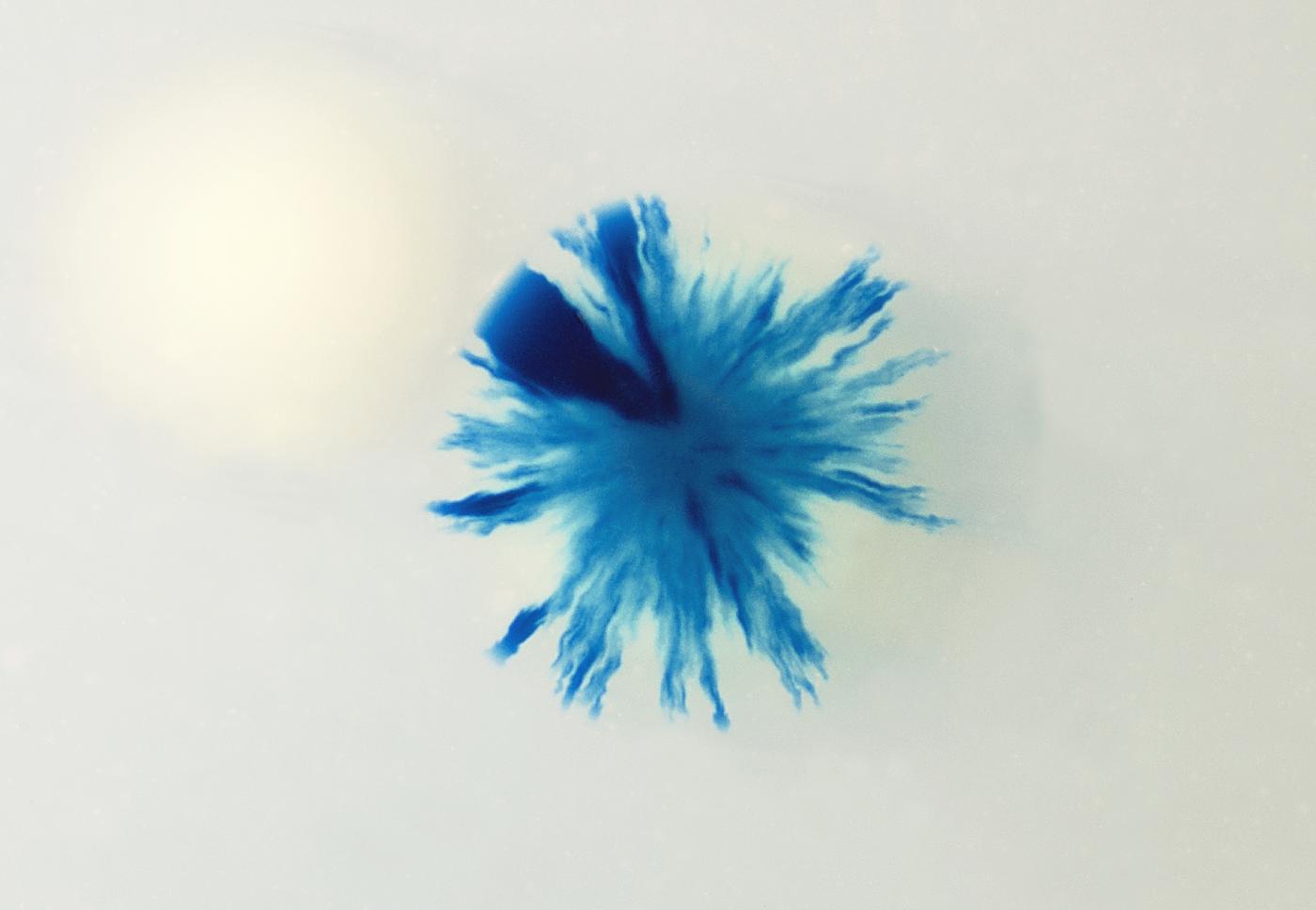

Vibrio cholerae is a highly motile bacterium with modest nutritional requirements whose natural reservoirs are found in humans and in certain cases the environment. The disease is caused by ingesting contaminated water or food. Man plays both the role of culture medium and means of transport for V. cholerae; once in the intestines, the bacteria secrete cholera toxin, which leads to the severe dehydration characteristic of cholera infection – loss of water and electrolytes can reach up to 15 liters per day. Diarrheal stools, massively contaminated by V. cholerae, and released in large quantities, are responsible for the spread of bacilli in the environment and fecal-oral transmission. The incubation period, from a few hours to 5 days, and the healthy carriers, enable the transport of V. cholerae over short or long distances.

The main factors that encourage cholera transmission are socio-economic status and living conditions of populations. Densely concentrated populations in areas with poor hygiene facilitate the emergence and development of cholera outbreaks.

Factors that increase the risk of a cholera outbreak

The presence of the bacteria!

Damp, unsanitary conditions

- heavy seasonal rains

- floods/droughts

- estuaries/rivers/creeks

- inadequate sanitation

- climate change

A volatile political climate

- inadequate public health measures

Community-based/collective factors

- large gatherings/crowded conditions

- forced migration

- poverty

- unsanitary conditions

- limited access to clean water

- use of antibiotics

Individual factors

- poor hygiene

- unsafe food

- a weak immune system

- a low level of education

- high-risk behavior

- cultural beliefs and practices (e.g. burials)

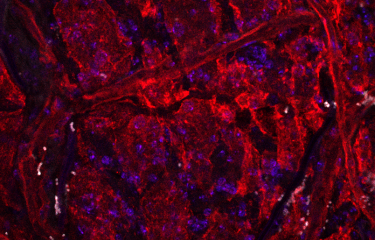

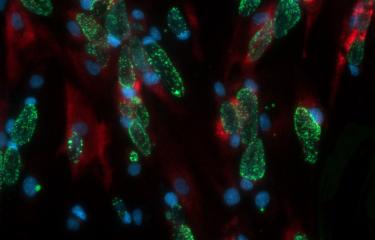

Colony of the pathogenic cholera bacterium, Vibrio cholerae, possessing blue areas, indicating the successful artificial fusion of the two chromosomes to result in a single chromosome strain. © Institut Pasteur/Thibault Rouxel and Marie-Eve Val, Plasticity of the bacterial genome

The history of cholera outbreaks finally elucidated

Scientists from the Institut Pasteur and the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, in collaboration with several international institutions, recently published a landmark study in the journal Science. They traced the history of cholera outbreaks in Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean over the past 60 years. Their research revealed that the cholera bacterium had been introduced at least 11 times into Africa over a period of 44 years, always from Asia, and that human populations were the main vectors for disease dispersal throughout Africa.

François-Xavier Weill, Head of the Institut Pasteur's Enteric Bacterial Pathogens Unit

These findings show that cholera was not only introduced into Africa in 1970 before subsequently taking up residence there, but is repeatedly introduced on a regular basis. Starting from two prime zones of introduction in West Africa and East Africa, epidemics spread along preferential routes to persistence zones such as the Lake Chad basin or the Great Lakes region.

"This work has implications for the control of cholera pandemics and paves the way for a better control strategy. The areas of Africa most susceptible to the introduction of cholera will have to be targeted more specifically in order to stem the cholera waves before they sweep the rest of the continent," point out the researchers.

This research was based on a unique collection of cholera vibrio strains, formed by the Institut Pasteur and kept there for nearly 50 years (the Institut Pasteur has long-standing expertise in cholera research – see below in "The Vibrios and Cholera CNR at the Institut Pasteur"), as well the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute's the genome collection – enabling the scientists to cover not just Africa but also other world regions. In a second study, the team focused on Latin America, where epidemic cholera reemerged in 1991 alongside sporadic cases of low-level disease. This revealed that the risk of large-scale outbreaks varies depending on the V. cholerae strain responsible. The massive epidemics seen in Peru in the 1990s and Haiti in 2010 were caused by the Asian pandemic strain, whereas the sporadic cases in Latin America arose from local strains. "One of the major findings of this study was that we should be careful not to confuse vast cholera pandemics with tens of thousands of victims with local outbreaks that appear not to have epidemic potential," emphasize the researchers.

Marie-Laure Quilici,

Head of the Vibrios and Cholera National Reference Center at the Institut Pasteur

All of these studies demonstrate the added value of whole-genome sequencing of V. cholerae strains for cholera surveillance, prevention and control. Our research illustrates the benefits of combining epidemiological and laboratory data during investigations of epidemics, and lends weight to the message recently issued by the WHO's Global Task Force on Cholera Control [see below] to public health practitioners, which recommends systematically combining these two approaches to improve epidemic management.

a 90% reduction in cholera deaths by 2030

An ambitious new strategy to reduce the number of deaths from cholera by 90% by 2030 was recently launched by the Global Task Force on Cholera Control (GTFCC), a network of more than 50 United Nations and international agencies, academic institutions and NGOs that supports countries affected by the disease. Urgent action is needed to protect communities, prevent transmission and control outbreaks.

Cholera: understanding the link between the world’s major outbreaks paves the way to a better control strategy

Find out more in the press area at pasteur.fr

Genomic analysis of more than 1,200 strains of Vibrio cholerae by scientists from the Institut Pasteur and the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, in collaboration with several international institutions, revealed for the first time the link between the different outbreaks of cholera since 1961. Their findings were published in the journal Science on November 10, 2017.

Cholera today

The world is currently witnessing its seventh cholera pandemic. The first six pandemics killed millions of people after the infection spread from its original reservoir in the Ganges delta in the 19th century. The seventh pandemic began in South Asia in 1961, reaching Africa in 1971 and America in 1991. Recent studies, in which the Institut Pasteur has been actively involved, have proven this historical trajectory and demonstrated the link between all the major cholera outbreaks. In May 2011, the World Health Assembly recognized the "reemergence of cholera" as a global public health problem and adopted a resolution to improve cholera control. At that time the UN stated that "with increasing populations living in peri-urban slums and refugee camps, as well as increasing numbers of people exposed to the impacts of humanitarian crises, the risk from cholera will likely increase worldwide". The events currently unfolding in Yemen have tragically proved it right. While the use of oral cholera vaccines can play an effective role in helping control cholera, improving access to drinking water and basic sanitation services in many countries – together with the efforts of local communities – are vital in the fight against this disease (and many other waterborne infections).

The Vibrios and Cholera CNR at the Institut Pasteur

The National Reference Center (CNR) for Vibrios and Cholera, based at the Institut Pasteur in the Enteric Bacterial Pathogens Unit, is responsible for monitoring cholera and investigating the biodiversity of the different strains circulating worldwide. When the French government set up the country's infrastructure for infectious disease surveillance in the 1950s, it decided that this center of excellence should be based at the Institut Pasteur because of its long tradition of expertise in this disease. The Cholera and Vibrios Unit was officially designated a National Reference Center (CNR) in the 1970s. Under the national decree of November 29, 2004 laying down the procedures for designating CNRs and setting out their missions, the Vibrios and Cholera CNR is tasked by the French Ministry of Health, especially the General Directorate of Health and the French National Public Health Agency (Santé publique France), to carry out microbiological surveillance of cholera and other Vibrio infections (caused by non-cholera vibrios).