A former member of the French Second Armored Division and Companion of the Liberation, François Jacob risked his life to defend the fundamental values of democracy and freedom. He was a brilliant scientist who spent his entire career at the Institut Pasteur and who inspired many researchers who followed in his tracks.

François Jacob never missed an opportunity to demonstrate his commitment to the Institut Pasteur. On November 14, 2012, alongside the President of the Republic, he was delighted to be able to inaugurate the new building that bears his name.

The obituary below was written by Michel Morange, a former pupil of François Jacob who works as a biologist and science historian.

Press release

Paris, April 22, 2013

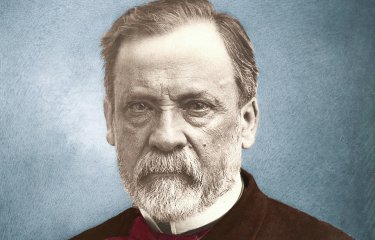

François Jacob (1920-2013)

François Jacob began his career at a relatively late stage. His original plan to become a surgeon was interrupted in June 1940 when he refused to accept the French surrender and he joined General de Gaulle in London. For four years, he fought alongside the Free French Forces in Africa and then in France, where he was severely wounded during the summer of 1944. François Jacob was awarded the highest French World War II military decoration, the Companion of the Liberation, and he subsequently became Chancellor of the Order of the Liberation.

After the war, and since he was no longer able to pursue his career as a surgeon, he worked in various fields, including antibiotic production, before hearing about the emergence of a “scientific revolution” that was taking place through the interplay of physics, genetics and microbiology. He was keen to contribute to this exciting new movement, and André Lwoff, one of the few French researchers involved in this biological revolution, invited Jacob to join his laboratory at the Institut Pasteur in Paris, where he enjoyed a meteoric rise to prominence within the scientific community.

Fifteen years later, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with André Lwoff and Jacques Monod for having devised the “operon model”, the first model to describe the mechanisms that regulate gene activity (or expression). In the meantime, he had also helped describe the complex interaction between bacteria and their viruses, bacteriophages, and, working with Elie Wollman, had proposed the mechanisms by which bacteria can exchange genetic information. François Jacob’s particular skill in all of these major research projects was his ability to conceptualize specific molecular mechanisms underlying complex observations and abstract paradigms.

The development of the operon model had a major impact on biology as a whole, both because it demonstrated the value of pooling experience in biochemistry and genetics and because it answered a question that geneticists had been asking for more than thirty years. It took just four more years for the Nobel Committee to recognize the importance of this major discovery.

In the late 1960s, along with many other molecular biologists, François Jacob decided to stop using bacteria as research models and favor more complex organisms. He chose to work with mice, which are genetically close to humans, and felt that this research could contribute to the work of the Institut Pasteur, to which he was still deeply committed. Jacob’s early work with mice was difficult, because it took time to build suitable tools for analyzing complex organisms and their embryonic development. But he had made the right decision, since mice are now the models of choice used by scientists for the reproduction and analysis of human diseases. The cell system chosen by François Jacob to facilitate research into embryonic development in mice was also groundbreaking: the teratocarcinoma cells studied in his laboratory are the ancestors of the stem cells that are now grown in hundreds of laboratories across the world.

rançois Jacob’s scientific authority left its mark on all those who were lucky enough to work with him. His immense scientific knowledge combined with his life experience fuelled his lifelong commitment to combating racism and preventing the misuse of genetic information.

François Jacob also analyzed the impact of the scientific breakthroughs in which he played a part. In his work La logique du vivant, he explored how the rapid growth of molecular biology can be seen in the context of the overall history of life sciences. In several other works, such as Le jeu des possibles, he described the specific features that characterize scientific knowledge as opposed to other types of knowledge. All these works demonstrate a substantial degree of originality in both style and content, as does Jacob’s autobiography La statue intérieure.

The death of François Jacob marks the end of a golden age of biology; he leaves behind a huge void.

--

Illustration - Copyright Institut Pasteur

Capation - François Jacob (1920 - 2013)