Louis Pasteur: a universal legacy

This year marks the bicentenary of Louis Pasteur's birth. His reputation speaks for itself, with streets and schools named after him in France and across the world. His immense legacy can even be seen in our homes, in the "pasteurized" products derived from one of his discoveries. And it was Pasteur who laid the scientific foundations for the principles of hygiene, which took on such importance during the pandemic. Louis Pasteur himself always avoided shaking hands, and if he ever made an exception he would wash them immediately. While Pasteur is famous for his rabies vaccine – which earned him the title "benefactor of humanity" –, the full breadth of his scientific achievements is less well known, despite the fact that they continue to have an impact on our daily lives and on today's research and medicine. We take a closer look.

Drawing by Fabrice Hyber.

Drawing by Fabrice Hyber.

From molecules to ferments

Louis Pasteur was not a physician, he was a chemist. And it was in the field of chemistry that he made his first major discovery: molecular asymmetry. By showing that there are two types of tartrate, with the same composition but different forms, each one a mirror image of the other, he transformed the prevailing perception of molecules – they were now seen as three-dimensional objects. Although it may seem abstract, this first scientific achievement laid the foundations for Louis Pasteur's reputation. He then turned his attention to fermentation, a process believed to be linked to microorganisms known as "ferments," although their role was not understood. Pasteur elucidated it in 1857 and stated that "fermentation, far from being a lifeless phenomenon, is a living process." He demonstrated that fermentation is caused by microbes, with a specific microbe associated with each type: the microbe that caused lactic fermentation, which served to make cheese, was different from the ferment behind alcoholic fermentation in wine or beer production. This discovery revolutionized the food industry, which gradually began to use selected yeast strains and other microorganisms in production processes.

Equipment used by Louis Pasteur for his work on crystallography: a mineralogy microscope; a model made of wood, cork and card; and flasks containing crystals. |

L’ancien Hôpital pasteur, aujourd’hui Pavillon Louis Martin. Les balcons permettaient de circuler à l’air libre entre les chambres. |

While "pasteurization" was gradually adopted and is now a recognized standard in food hygiene, Louis Pasteur's contribution to hygiene went much further. In surgery departments in the 19th century, 4 out of every 5 deaths were caused by infection. After reading Pasteur's work on fermentation, British surgeon Joseph Lister became convinced that postoperative infection – referred to at the time as putrefaction – was caused by microscopic organisms. He decided to wash the wounds of his surgery patients with carbolic acid and published his method in 1867, referring to Pasteur's work. It was the beginning of antiseptic techniques. Pasteur went one step further, asking surgeons to wash their hands between each operation and to sterilize linen, dressings and instruments – this was asepsis, one of Pasteur's major contributions to hospital hygiene. As Pasteur's germ theory of disease began to take shape, he also recommended that contagious patients should be isolated as soon as they were admitted to hospital in "pavilions," each housing one specific disease. This led to the construction of "pavilion-type" hospitals from 1880 onwards. Through his discoveries, methods and advice, Louis Pasteur was one of the pioneers of hygiene, and his principles – such as hand-washing – continue to govern our everyday behavior even today.

If Pasteur had been a surgeon...

It was with these words in a speech to the French Academy of Sciences on April 29, 1878, that Louis Pasteur advocated asepsis: "If I had the honor of being a surgeon, imbued as I am with the knowledge of the danger of exposure to the germs spread on the surface of all objects, particularly in hospitals, not only would I use only thoroughly cleaned instruments, but, after having cleaned my hands with the greatest of care, I would subject them to rapid flaming (...). I would use only lint, bandages and sponges previously exposed to air temperatures of 130 to 150°C. I would use only water that had been heated to temperatures of 100 to 120°C..."

The advent of microbiology

The paper on lactic fermentation published by Louis Pasteur was regarded as the founding treatise for microbiology. In 1858, Pasteur set up his laboratory in the attic of the École Normale Supérieure in Paris' Rue d'Ulm, where he began his research on the spontaneous generation theory. At the time, many believed that life arose "spontaneously" from nonliving matter. It took multiple experiments and many battles along the way for Pasteur to refute this theory.

Gooseneck balloons used by Louis Pasteur to demonstrate the theory of spontaneous generation was impossible, 1878. © Institut Pasteur/Musée Pasteur |

One of his demonstrations used a swan neck flask to show that a nutrient broth in equilibrium with the ambient air remained sterile as long as it was protected from dust particles in outside air. But as soon as it came into contact with these particles, microorganisms began to proliferate. Louis Pasteur ultimately proved his germ theory, but not without considerable difficulty, since it went beyond the realm of science and impinged on the philosophy and belief systems of the time. Pasteur went on to explore microbes more than anyone else had ever done, showing that they are everywhere – in air and water, on the objects around us – and elucidating their role in both fermentation and putrefaction – a natural process to recycle living elements –, and later in diseases in animals and humans.

Diseases in wine and worms

One aspect that characterized Pasteur's career was that he was approached to solve quite specific problems in a variety of different fields. In 1863, Napoleon III asked him to study diseases in wine. Wines were turning sour, and this was a major problem because a treaty had just been signed to increase exports of French wine to Britain. Louis Pasteur again observed that microbes were to blame, and he suggested heating wine to a temperature of between 60 and 100°C after fermentation to stop contamination – a process that others came to call "pasteurization" (see inset on "Pasteurization" below). In 1865, Pasteur was again called to the rescue by one of his former professors, a chemist who had become a senator for the Gard department. This time, the challenge was to save the silk industry, which was under threat because of silkworm diseases. Louis Pasteur set up a laboratory in the Cévennes region and observed that silkworms were affected by two diseases: pebrine and flacherie. He then showed how the diseases could be prevented, by selecting healthy eggs for one and by applying hygiene measures in silkworm farms for the other. His work saved the silk industry in France and abroad, and would guide his later research on infectious diseases in animals. Pasteur also conducted research on beer and recommended techniques for monitoring fermentation under a microscope, which would subsequently be applied in many breweries. This incredibly useful research, as well as his later work, can be summed up in a famous quotation by Louis Pasteur:

There are science and the applications of science, bound together as the fruit of the tree which bears it.

Louis Pasteur in a wine cellar in Arbois, assisted by his two collaborators Duclaux and Gernez (or Lechartier) and a wine grower. Image taken from a series of pictures illustrating the work of Louis Pasteur with text on the back, published around 1900 by the Chocolaterie d'Aiguebelle. © Institut Pasteur/Musée Pasteur. |

"Pasteurization" is now part of our daily lives – it is used to preserve milk, cheese, fruit juice, tomato purée, beer and cider. But the history of the process began with a quite specific – and quite French – problem: how to preserve wine. In 1863, French wine producers found themselves in a tricky situation: their wines, exported in huge quantities to Great Britain, were often undrinkable on arrival, as if affected by a strange disease. The economic stakes were so high that Emperor Napoleon III called on Louis Pasteur, known for his research on alcoholic fermentation, to "search for the causes of the wine diseases and identify means of preventing them." It was in the vineyards of his home town of Arbois in the Jura that Louis Pasteur began his work on wine. From his makeshift laboratory, he proved that the diseases affecting wine were caused by microbial contaminants. To solve the problem, the development of these harmful germs had to be prevented or stopped. On April 11, 1865, Pasteur filed a patient "for a process for the preservation of wine": "Wine does not spoil if the microbes are killed beforehand. A simple, practical method is to heat the wine to a temperature between 60 and 100°C." Although the principle of heating had been known for some time, Louis Pasteur turned it into a scientific process with clear theoretical bases, making wine "the most healthy and hygienic of drinks." His "pasteurization" (a term used for the first time in Germany or Hungary around 1867) spread like wildfire through Europe, and machines of all types were devised to perform the process, culminating in industrial applications in the early 20th century. The method is rarely used for wine these days because it can affect the taste. But it is still used to preserve beer (Carlsberg was the first pasteurized beer) and especially milk – on the recommendation of a German chemist in 1866 –, and its use gradually spread to many other drinks and foods.

Louis Pasteur's jubilee at the Sorbonne, 1892. © Institut Pasteur

Edward Jenner invented vaccination; Louis Pasteur invented vaccines.

Was Louis Pasteur the first to work on vaccination?

Well before Louis Pasteur, a British physician, Edward Jenner, sought a way of immunizing people against smallpox, a devastating disease at that time. In 1796, he showed that people could be protected from infection if they were inoculated with pus from the blisters of a mild cattle disease similar to smallpox, known as cowpox (or "vaccine" in French). Pasteur assumed the cowpox virus to be an attenuated form of the smallpox virus and he wondered whether it might be possible to immunize against other diseases using an attenuated form of the causative microbe. In 1879, somewhat by chance, he obtained an attenuated variety of the bacterium responsible for fowl cholera. Not only did this attenuated form fail to kill the fowl; it also protected them from virulent bacterial strains. Pasteur then applied the method to other bacteria, including sheep anthrax bacteria, and this led to his famous demonstration in Pouilly-le-Fort in June 1881: the 25 sheep that he immunized survived inoculation with the anthrax bacillus, while 25 other non-"vaccinated" sheep died. Pasteur gradually began to convince the public that they could be protected from a disease by being inoculated with an attenuated microbe. He presented his research to the International Medical Congress in London in 1881 and named his process "vaccination" (after the French word for cowpox, "vaccine"), as a tribute to Jenner. But it was indeed Louis Pasteur who first understood how to develop vaccines.

Why did Louis Pasteur work on rabies?

Despite his achievements with animal diseases, Pasteur understood that he would only be able to cement the success of his theories by tackling human diseases. Rabies seemed to be an excellent candidate as it could be studied in animals. And more importantly, although rabies did not occur that often, it had a major psychological impact on the population because of the horrendous way in which infected people died. Studying a microbe that he could neither see nor grow in culture (in reality it was a virus and not a bacterium) was a tricky task for Pasteur. But he managed to conserve the virus by passing it serially from rabbit to rabbit, and to attenuate it – or at least so he thought (see below) – by suspending spinal cord sections from rabid rabbits in flasks lined with potash to dry them out. He immunized dogs, starting by inoculating cord tissue dried for 14 days, then the next day using tissue dried for 13 days, and so on. Since the incubation period for rabies in humans bitten by a rabid dog is several weeks, Pasteur believed that it would be possible to immunize them immediately after they had been bitten, before the virus reached the brain. On July 6, 1885, despite some reservations, Pasteur agreed to treat Joseph Meister, a boy from Alsace who had been bitten 14 times. He was vaccinated by Dr. Jacques-Joseph Grancher. A few months later, as treatment began on another child, Jean-Baptiste Jupille, Pasteur declared to the French Academies of Sciences and Medicine on October 26 and 27 that he had "conquered rabies." On March 1, 1886, Pasteur announced that he had vaccinated 350 people, with just one failure.

What was the scientific impact of these discoveries?

One very important point is that Pasteur soon realized that he was not actually inoculating a live attenuated microbe, as he had done with his previous veterinary vaccines. The rabies virus had been killed. By understanding that patients could be vaccinated either with live attenuated microbes or with inactivated (killed) microbes, Pasteur paved the way for the development of vaccines against many different diseases, saving millions of lives. Live attenuated vaccines have been used for tuberculosis, measles and mumps, for example, while vaccines based on an inactivated microbe have helped tackle rabies, typhoid fever, influenza and hepatitis A. It was subsequently discovered that in some cases, people could be vaccinated by inoculating a molecule from the microbe (diphtheria, tetanus, hepatitis B, etc.).

Find out more

Professor Maxime Schwartz is the author of the book Pasteur, l'homme et le savant (Pasteur, the man and the scientist). See below.

In understanding the principle of immunization by the inoculation of non-virulent microbes, Pasteur paved the way for the development of vaccines to treat many diseases.

Pr Maxime Schwartz

Crowning achievement

|

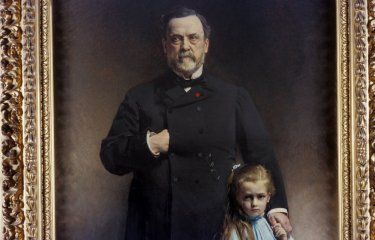

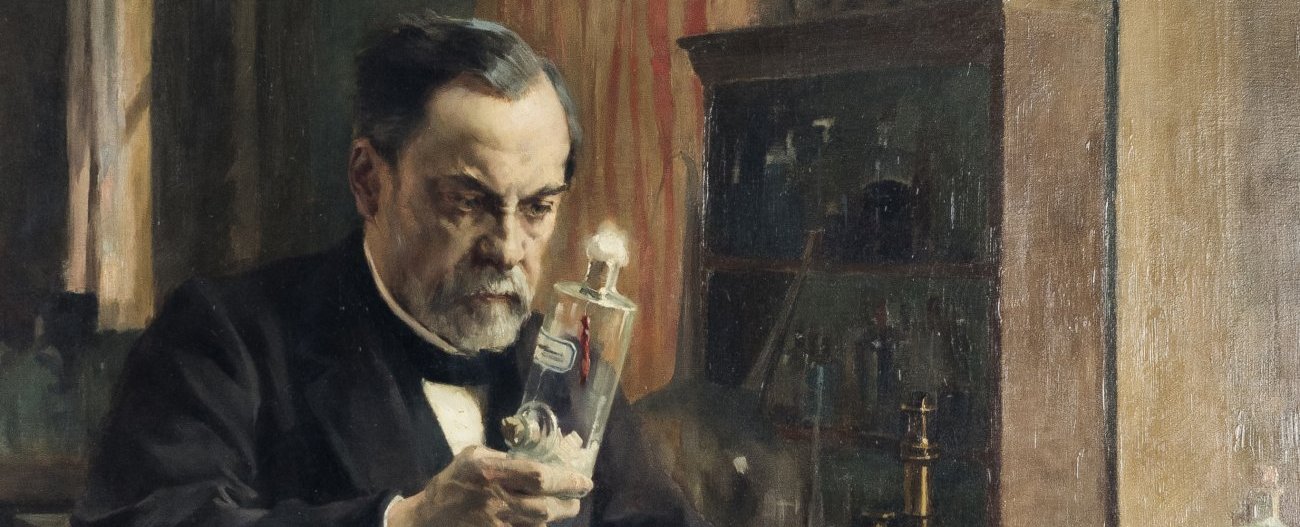

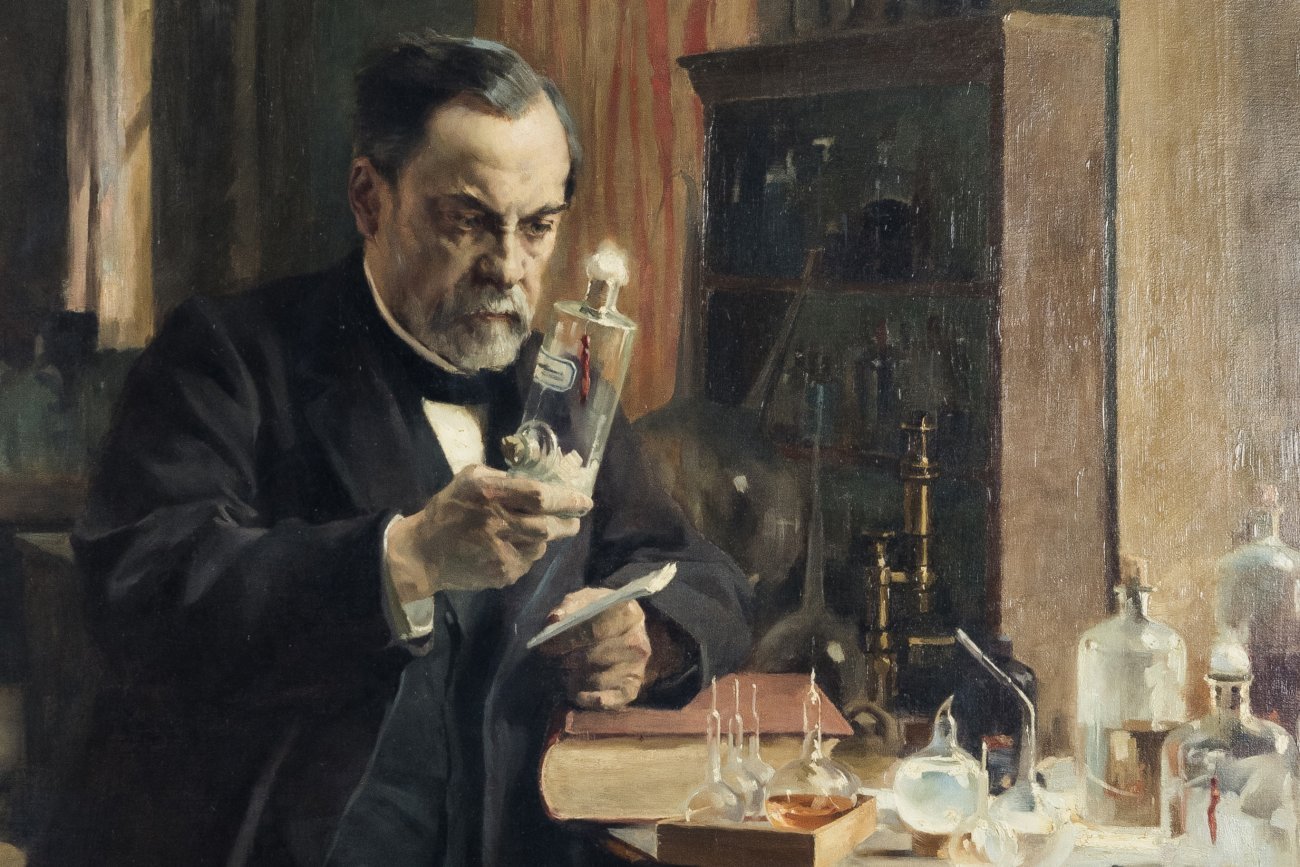

In this famous portrait by Albert Edelfelt in 1886, Louis Pasteur is holding a vial containing a rabid rabbit's spinal cord.

Gérard Eberl

Head of the Microenvironment and Immunity Unit

To paraphrase Louis Pasteur: the Pasteurian spirit means being prepared for luck to smile on us.

It's the enthusiasm and curiosity that, combined with strict scientific rigor, have often made it possible to expand the limits of our knowledge. It also means always being open to the world and to society, through the international network and its public health missions.

Lulla Opatowski

Head of the Modeling Group in the Epidemiology and Modeling of Bacterial Escape to Antimicrobials Unit

Laure Bally-Cuif

Director of the Department of Developmental and Stem Cell Biology and head of the Zebrafish Neurogenetics Unit

It's about gauging the importance of observation. Because while our scientific choices are guided by knowledge and reasoning, the ability to precisely describe a phenomenon reveals exceptions that will always go beyond our theories.

It's a particular way of doing science, taking the view that knowledge in its simplest form is a wonderful gift with an unexpected impact.

Shahragim Tajbakhsh

Head of the Stem Cells and Development Unit

Olivier Schwartz

Head of the Virus and Immunity Unit

It's about seeking to understand the workings of the living world to improve human health; always being curious, open to the world, ambitious and collaborative. It's about working as a team!

It's an openness to the world in all its fullness and diversity – as we see in the various institutes in the Pasteur Network, each of which has contributed to the great Pasteurian story, like pearls from the same necklace.

Anna-Bella Failloux

Head of the Arboviruses and Insect Vectors Unit

Lluis Quintana-Murci

Lluis Quintana-Murci Holder of the Chair in Human Genomics and Evolution at the Collège de France and head of the Human Evolutionary Genetics Unit

It's about curiosity, mutual support among colleagues, and above all a great freedom of thought and action in research. At the Institut Pasteur I feel free, and that is something precious.

In France and abroad, the bicentenary of Louis Pasteur's birth is a unique opportunity to pay tribute to him and share his legacy. Go to pasteur2022.fr (in french) to find out more about the celebrations and events that will be held throughout this special year.

Some examples:

February 7, 2022

La Poste began issuing a stamp featuring a portrait of Louis Pasteur. Designed by Patrick Dérible on the basis of a photo proposed by the Pasteur Museum and engraved by Pierre Bara, the stamp and souvenir set are now available to purchase.

July 9, 2022

The 8th stage of the 2022 Tour de France will start in Dole, Louis Pasteur's birthplace.

December 7, 2022, in Paris

Conference on "Major epidemics," organized by the Institut Pasteur and the French Academy of Sciences and open to all. It will explore the major epidemics that have affected human populations and will also look at animal epidemics.

December 8, 2022, in Paris

Public conference on "Pasteur: the visionary," organized by the French Academy of Sciences and the Académie française. Renowned scientists will discuss the milestones in Pasteur's career, from chemistry to vaccines and viruses, and their resonance with today's science.