Southeast Asia faces the rise of emerging diseases

Continuous economic development in Southeast Asia has left a considerable impact on ecosystems, unleashing infectious diseases like dengue fever and leptospirosis. A program coordinated by the Institut Pasteur, with the support of AFD, is identifying the risk factors behind these diseases and improving diagnosis capacities to provide better treatment.

Population growth and economic development are creating serious consequences for natural ecosystems. Southeast Asian countries must deal with rapid growth that has led to both acute urbanization and an intensification of agricultural practices. The resulting disruptions in ecosystems contribute to the emergence of diseases and to their spread to areas not previously affected, as well as to the appearance of new diseases.

It’s against this backdrop that the Institut Pasteur, with support from Agence Française de Développement (AFD), has launched ECOMORE II. The project aims to broaden understanding of the specific changes causing the emergence of infectious diseases. It will also measure the impact of surveillance systems and heightened national and regional cooperation, which were launched in phase one, in response to these diseases.

A word on dengue & leptospirosis

Leptospirosis is an infection transmitted through water, from animals to humans. Dengue fever, on the other hand, is transmitted by mosquitoes.

Diagnosis is difficult because the two diseases have similar clinical symptoms: high fever, aches and pains, fatigue, etc.

The risk of severe consequences is high for infected individuals, who are often from among the poorest and most vulnerable populations. In severe cases of leptospirosis, the mortality rate can reach 20%.

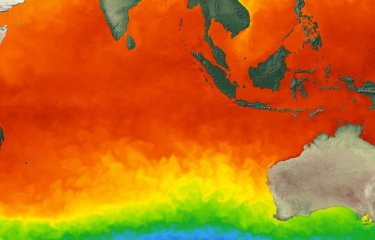

This second phase of the project will also analyze the impact of climate change on the emergence of diseases in the study area. The most significant risks come from waterborne and mosquito-borne diseases, whose emergence stems in part from changing weather patterns and intense land use.

Five Southeast Asian partners share their experience of what are becoming major public health issues in their country: dengue fever in Cambodia, Laos, and the Philippines, and leptospirosis in Myanmar and Vietnam.

We meet some of the key players in the project.

Urgently raising awareness

In Vietnam, authorities are trying to ascertain the number of leptospirosis cases and identify the main risk factors. To this end, the National Institute of Hygiene and Epidemiology (NIHE) in Hanoi is conducting an epidemiological survey in three provinces (in northern, central and southern Vietnam) to analyze various climatic and social environments. Leptospirosis has received relatively little attention in Southeast Asia, particularly in Vietnam. The first step was thus to raise awareness among hospital physicians about how the disease circulates and to strengthen diagnostic capacity by the NIHE laboratory.

“It’s a disease we never thought about in our diagnoses,” admits Dr. Nguyen Trung Tuyen, physician and head of the infectious diseases department at Thai Binh Hospital. “We’ve only really been familiar with leptospirosis for ten years. At university, discussion of the subject was very brief in my time.”

Up to now, hospitals lacked the clinical training needed to detect the presence of the disease, whose symptoms can be similar to those of dengue fever. Hospitals lacked information on the laboratory tests needed to confirm leptospirosis cases. As part of the ECOMORE II project, doctors have been trained in clinical suspicion (forming a hypothesis based on the symptoms), and laboratories can now confirm diagnoses.

At Thai Binh Hospital, for example, diagnostic information posters have been posted in all units. Since then, the number of suspected cases across the province increased from 1 or 2 per year to 135 over seven months. Patients are also interviewed using a questionnaire designed to analyze their lifestyle and environment in order to better identify risk factors.

Using technology for vector control

In Laos, the priority is to develop risk-assessment and control tools for dengue fever, to minimize public health impacts.

The aim of the study conducted by the Institut Pasteur du Laos (IPL) is to better understand transmission of dengue fever in Vientiane, the country’s capital. To this end, entomological data produced by IPL will be combined with environmental and meteorological data collected by the French National Research Institute for Development (IRD) and French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) partners. This combined data will provide an “epidemics simulator” that can be used by health authorities to predict the appearance and spread of epidemic peaks in Vientiane. This system is essential for the goal of reducing the impact of dengue fever.

In the light of the scale of epidemics in the capital, some innovative initiatives are being developed at the district level. Dr. Chantone is a physician and dengue fever specialist at the Xaysettha Provincial Hospital. After training himself online and participating in training from the Institut Pasteur, he developed several mobile applications to facilitate the collection and processing of data in the field.

“The application is used by volunteers from 48 villages,” he explains. “They make field visits to inspect mosquito breeding sites such as water containers and waste sites. They then destroy the sites and report the cases. If the larva infestation rate is too high, an alert is immediately sent by Line [an instant messaging application] and Facebook to our team.” The GPS coordinates of the site are also communicated.

“This way, we can observe the villages in which vector control [a set of control measures against vector mosquitoes] is effective, and we can above all identify areas where larger-scale action is needed,” explains Dr. Chantone. “When the instructions are not respected, we contact the village chief, who will set up weekly clean-up campaigns with the advice of our teams.”

Protecting children from deadly diseases

In Cambodia, the objective is to determine whether implementation of an integrated vector control strategy in schools can reduce peak dengue fever epidemics.

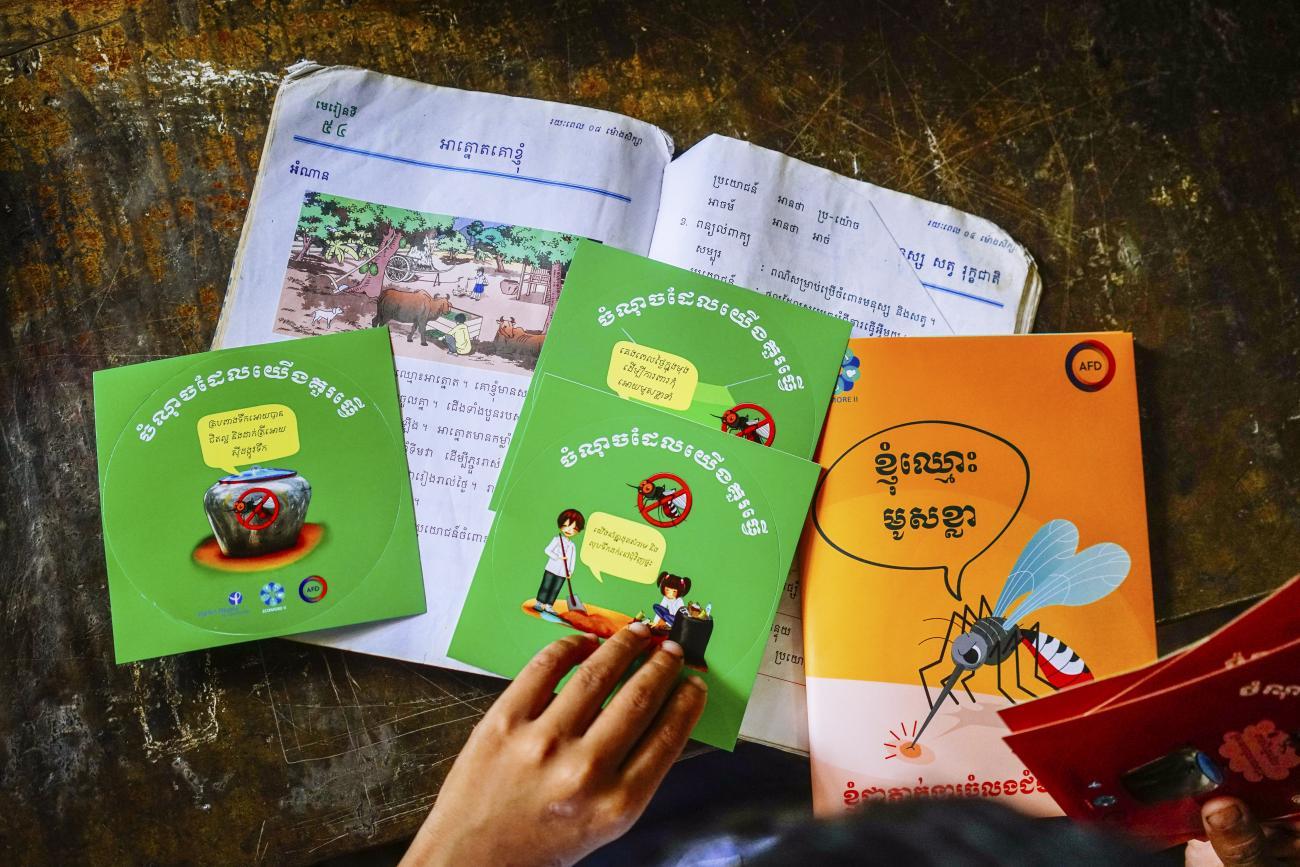

Sony Yean has been working for the ECOMORE project for two years, within the Medical Entomology Unit at the Institut Pasteur du Cambodge (IPC). “We are working in schools, not only with children but also with teachers and school principals, so that they understand the importance of vector control measures,” she says. “Other measures are being taken to reduce the spread of mosquitoes. These include insecticide self-dissemination techniques, clean-up campaigns, installation of traps, and also awareness raising on the use of plastic, where mosquitoes develop.”

IPC has adapted its tools to reach students, who receive a notebook and stickers detailing good and bad practices. The objective for the team of the IPC Epidemiology Unit is to then measure the evolution of dengue fever contamination in schoolchildren over a period of months. To do so, saliva tests and active monitoring of “dengue fever syndromes” in all children will be carried out in the villages around the affected schools, in order to assess the effectiveness of this strategy in communities.

Training doctors to detect symptoms early

Dr. Thu Zar Myint Than is the national coordinator of the ECOMORE II project in Yangon (formerly Rangoon, Myanmar’s largest city). Her work consists of training interns and hospital physicians participating in the study to collect data that will help analyze risk.

“The risk factors for leptospirosis are numerous,” she says, “especially for people in contact with environments potentially contaminated with animal urine, in particular from rats, dogs or cattle.”

To conduct the survey, the ECOMORE II project relies on hospitals in the region. “We work with ten hospitals that identify suspected cases of leptospirosis and send us blood samples. We analyze them in the NHL laboratory in Yangon, and when the case is positive or suspect, we conduct a field investigation,” says Dr. Thu Zar Myint Than. “We try to confirm the diagnosis, which requires an additional sample a few days later. At the same time, we look for possible causes of disease transmission in the patient’s environment and raise their awareness about the risks around them.”

“At the end of the project,” she says, “we want to share our results with the relevant ministries so that we can work together to prevent and control the spread of leptospirosis in urban and suburban areas, especially during the rainy season. Doing so will enable health authorities to make recommendations for communities.”

Tools for real-time analysis of epidemics

In the Philippines, the project seeks to evaluate the effectiveness of a new method of insecticide self-dissemination via mosquitoes themselves, on a citywide scale (Lipa City, south of the Manila megapolis) in order to reduce the impact of dengue fever.

The Research Institute of Tropical Medicine (RITM) will conduct entomological surveillance to monitor the evolution of tiger mosquito (Aedes) populations, which will be correlated with seroconversion surveys among children. An original management tool has been set up by the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (LSTM). It integrates all the collected data and will serve as a tool for intervention decisions by health authorities.

This first collaborative project between the Institut Pasteur and the RITM coincides with the Philippine Department of Health’s announcement on August 6, 2019, to the effect that there were more than 140,000 dengue cases and 622 deaths related to this disease in the country. Testing innovative vector-control strategies and providing a tool for real-time analysis of dengue epidemics thus seems crucial for helping authorities minimize the spread of the disease.

Emerging diseases and climate change

At the regional level, the objective of the ECOMORE II project is also to work on the link between the emergence of these diseases and the various climate scenarios. The Institut Pasteur is therefore collaborating with the French National Research Institute for Development (IRD) to model the evolution of dengue fever and leptospirosis according to these different scenarios, which include the intensification of risk factors such as higher rainfall.

“The idea is that, eventually, local decision-makers connect to the site, enter the name of their region and immediately see the projection of the impact of climate change and of the evolution of the diseases studied,” says Benjamin Sultan, an IRD researcher and climate change specialist.

“It’s a powerful awareness-raising tool. The hope is that some countries, after becoming aware of those projections, will want to go further in their climate change adaptation and mitigation plans.”

A regional project based on south-south cooperation

ECOMORE II strives to promote and share the results of field studies regionally. Annual steering committee meetings bring together all the stakeholders involved in the implementation of the project. In addition, the project provides for exchanges in which experts from the region participate. These exchanges include joint training in new laboratory diagnostic techniques, cross-cutting technical workshops, and mutual visits to the sites where field studies are implemented.

These collaborative activities are also developed between partners and national authorities. For example, the Thailand International Cooperation Agency (TICA) organized training in collaboration with Kasetsart University in Bangkok and the Institut Pasteur du Cambodge (IPC) to improve mosquito identification skills by Cambodian entomologists from the National Malaria Center of Cambodia (NMC) and the IPC’s Medical Entomology Unit.