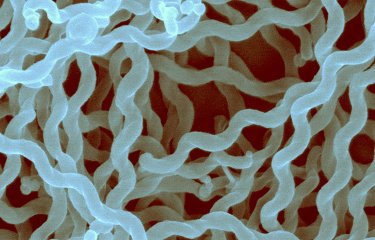

An international research group has revealed several new bacterial species that may be responsible for leptospirosis, an emerging animal-borne disease, using genome sequencing. Every year, more than a million people contract leptospirosis, an emerging animal-borne disease caused by bacteria belonging to the genus Leptospira. To improve our understanding of this disease, the genomes of several species of Leptospira were sequenced by scientists from the Institut Pasteur International Network. Their findings, published in the journal PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, reveal 30 new species and provide new information about the genetic content of the bacteria responsible for leptospirosis.

The genus Leptospira is currently divided into 35 species classified into three phylogenetic clusters that historically correlate with the level of pathogenicity of the species: saprophytic, intermediate, and pathogenic. The evolution of each of these clusters has been unclear and the virulence status of many species is unknown.

In the new work, a group of researchers from the Institut Pasteur International Network (IPIN) including Mathieu Picardeau, of the Institut Pasteur, France, and Frédéric Veyrier of the INRS-Institut Armand-Frappier, Canada, and other colleagues from the Institut Pasteur d’Algérie and the Institut Pasteur de Nouvelle-Calédonie studied 90 Leptospira strains isolated from 18 sites across four continents, including Japan, Malaysia, New Caledonia, Algeria, France, and Mayotte. The genome of each isolate was sequenced and compared to known Leptospira genomes.

Based on the genetic sequences, the team was able to identify 30 new Leptospira species. They organized the Leptospira genus, which now comprises 64 species, into four lineages or subclades, dubbed P1, P2, S1, and S2. The S2 subclade has never been described. In the P1— formerly known as pathogenic—lineage, they shed light on a phenomenon of genome reworking that may explain their evolved pathogenicity.

Mathieu Picardeau, co-senior last author of the study and researcher at the Institut Pasteur, explains “We have dusted off the Leptospira genus and gained more clarity of its diversity which will help researchers propose new standards on its classification and nomenclature. The implication of several new potentially infectious Leptospira species for human and animal health remains to be determined but our data also provide new insights into the emergence of virulence in the pathogenic species”.

Frédéric J. Veyrier, co-senior last author of the study and researcher at INRS-Institut Armand-Frappier, adds “This genus is an excellent model to study bacterial adaption to human or other hosts. Our data suggests that after ongoing ecological niche switch from free living to host-associated lifestyle (concomitant with gene expansion), a group of Leptospira are now stabilizing and restricting their lifestyle in specific niches. Our consortium will therefore continue to study in depth the characteristics of this unique genus and its evolution.”

Further studies will include detailing the unique characteristics of this genus and how virulence can emerge in these pathogenic species, in order to better determine their impact on human and animal health.

Source

Revisiting the taxonomy and evolution of pathogenicity of the genus Leptospira through the prism of genomics, PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, May 23, 2019

Antony T. Vincent1, Olivier Schiettekatte2, 3, Cyrille Goarant4, Vasantha Kumari Neela5, Eve Bernet1, 2, Roman Thibeaux4, Nabilah Ismail6, Mohd Khairul Nizam Mohd Khalid7, Fairuz

Amran7, Toshiyuki Masuzawa8, Ryo Nakao9, Anissa Amara Korba10, Pascale Bourhy2, Frederic J. Veyrier1, Mathieu Picardeau2

1 INRS-Institut Armand-Frappier, Bacterial Symbionts Evolution, Laval, Quebec, Canada

2 Institut Pasteur, Biology of Spirochetes unit, Paris, France

3 Université Paris Diderot, Ecole doctorale BioSPC, Paris, France

4 Institut Pasteur de Nouméa, Leptospirosis Research and Expertise Unit, Nouméa, NewCaledonia

5 Universiti Putra Malaysia, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Department of Medical Microbiology and Parasitology, Serdang, Malaysia

6 Universiti Sains Malaysia, Department of Medical Microbiology and Parasitology, Kubang Kerian, Malaysia.

7 Institute for Medical Research, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

8 Chiba Institute of Science, Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Laboratory of Microbiology and Immunology, Choshi, Japan

9 Hokkaido University, Department of Disease Control, Graduate School of Veterinary Medicine, Laboratory of Parasitology, Sapporo, Japan

10 Institut Pasteur d’Alger, Algeria