What is an antibiotic?

Antibiotics are drugs used to fight bacterial infections such as pneumonia, bronchitis, ear infections, meningitis, urinary tract infections, septicemia and sexually transmitted diseases. The discovery of antibiotics was a major milestone in medicine that has saved and continues to save millions of lives every year, but their effectiveness is threatened by the ability of bacteria to adapt and resist treatment. Antibiotics kill bacteria or stop them from spreading, but some bacteria become resistant and no longer respond to these drugs. This phenomenon is known as antibiotic or antibacterial resistance.

What are the causes of antibiotic resistance?

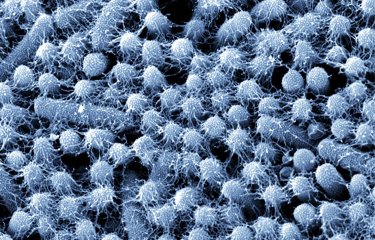

Bacteria can become resistant to antibiotics either through mutations or by acquiring resistance genes that confer resistance to one or more antibiotics. Bacteria are capable of exchanging genes, and this can be problematic if the genes make their host bacteria resistant to antibiotics. While resistance through mutation is rare, occurring in approximately one in every hundred million bacteria, resistance genes can be exchanged among bacteria with high frequency, affecting up to one in every hundred bacteria.

Resistant bacteria and resistance genes can be transmitted between humans, animals and the environment, both through direct contact and also through water or food, so the use of antibiotics in veterinary medicine and the disposal of antibiotics in the environment can also foster the emergence of new multidrug-resistant bacterial strains.

Antibiotic resistance does not just affect disease-causing bacteria. The friendly, non-pathogenic bacteria that colonize us and make up our microbiome, which is vital for our health, can also develop resistance, creating a reservoir of resistance genes that can then spread to pathogenic bacteria.

What are the effects of antibiotic resistance?

Taking antibiotics disrupts our microbiome and contributes to an increase in our reservoir of resistance genes. This is true for antibiotics prescribed for bacterial infections but it also applies when antibiotics are taken for no good reason, for example to treat viral infections such as colds or flu, on which they have no effect. The microbiome acts as a barrier, protecting us from infection by preventing colonization by potentially pathogenic bacteria. So taking antibiotics when they are not needed actually has a double negative effect, both disrupting the microbiome and its protective barrier and also contributing to the selection of resistant bacteria. This can increase the risk of a subsequent infection that is difficult to treat.

Underdosage of antibiotics, which can occur when treatment is interrupted mid-course or with the use of counterfeit drugs sold in some low-income countries, can also encourage the acquisition of antibiotic resistance.

Infections in humans and animals caused by resistant bacteria are harder to treat than those caused by non-resistant (or "susceptible") bacteria, because the choice of antibiotics that can be prescribed is more limited.

What are the different levels of resistance?

Some bacteria are resistant to several antibiotics; these are known as multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria. The most alarming MDR bacteria are:

- multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, bacteria in the digestive tract responsible for a large number of infections (Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae);

- methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; multidrug-resistant tuberculosis bacilli; and Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii, bacteria that infect the lungs of cystic fibrosis patients and cause nosocomial infections (infections acquired in healthcare facilities, especially hospitals and clinics).

In extreme rare cases, bacteria can be resistant to all available antibiotics used in humans. These pan-resistant bacteria can lead to a situation in which there are no possible treatment options.

How can antibiotic resistance be prevented?

It is vital to avoid the misuse or excessive use of antibiotics, which speeds up the development of resistance. It is important to realize that unnecessary antibiotic consumption has long-term negative effects both at individual level and for society as a whole. Efforts to limit antibiotic consumption do not just apply to human medicine; they also concern animals, especially livestock.

Hygiene remains a vital means of avoiding infections and the subsequent need for antibiotics. Although antibiotic resistance occurs all over the world, it is especially prevalent in countries with low levels of hygiene.

What you can do:

- Only take antibiotics if prescribed by your doctor

- Never share antibiotics with someone else

- Don't insist on being prescribed antibiotics if your doctor sees no need for them

- Apply basic hygiene measures to prevent infections

How to reduce the need for antibiotics?

Vaccination against bacterial diseases is a way of preventing the onset of disease and the subsequent need for antibiotics – which may ultimately prove ineffective because of antibiotic resistance. Vaccination also avoids the unwanted effects of antibiotics on our microbiome. Pneumococcal vaccination, for example, has led to a significant reduction in antibiotic resistance for this bacterial species.

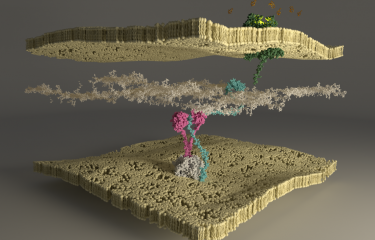

Given the increase in antibiotic-resistant bacteria and the difficulties in developing effective new antibiotics, various alternative strategies are under consideration. Phage therapy has been the focus of renewed interest among the scientific community over the past few years. This alternative to antibiotics is a promising avenue for research. It involves eliminating bacteria by using specific viruses (known as phages) to kill a given bacterial species. This targeted technique is a direct result of microbiologist Félix d'Hérelle's discovery of bacteriophages at the Institut Pasteur in 1917.

In May 2015, WHO launched a global action plan with the aim of preserving our ability to prevent and treat infectious diseases using safe, effective medicines. The plan sets out five objectives:

- to improve awareness and understanding of antimicrobial resistance;

- to strengthen surveillance and research;

- to reduce the incidence of infection;

- to optimize the use of antimicrobial drugs;

- to ensure sustainable investment in countering antimicrobial resistance.

Since the early 2000s in France, the national plan to preserve the efficacy of antibiotics has involved surveillance of bacterial resistance to antibiotics under the aegis of Santé publique France (previously the French Institute for Public Health Surveillance – InVS).

Who is affected?

Although antibiotic resistance can be observed in all countries, some are affected to a greater extent than others. Major contributing factors include the country's antibiotic consumption, hygiene and income level. Resistant bacteria are also found in animals and in the environment. Human medicine, veterinary medicine and environmental pollution by antibiotics therefore contribute to the increase in resistance.

According to WHO, half of all antibiotics used worldwide are given to animals. In several countries, livestock are constantly given low doses of antibiotics to speed up growth and promote weight gain. This practice, which is banned in the European Union, contributes to the selection of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, which can then be transmitted to humans. In France, the ÉcoAntibio Plans launched in 2011 led to a 45% reduction in overall exposure of animals to antibiotics over an eight-year period.

According to WHO, if no action is taken, "the world is headed for a post-antibiotic era, in which common infections and minor injuries which have been treatable for decades can once again kill." WHO sees antibiotic resistance as an emergency. In May 2024 it published a list of bacteria for which new antibiotics are urgently needed.

Further information: WHO updates list of drug-resistant bacteria most threatening to human health

FAQ

What is antibiotic resistance?

Antibiotic resistance is a natural phenomenon whereby a kind of natural selection occurs among bacteria in response to a treatment.

There are two mechanisms by which bacteria become resistant to an antibiotic:

- Mutation. The target of an antibiotic is affected and becomes insusceptible to the antibiotic.

- Acquisition of resistance genes. These resistance genes code for functions that render bacteria insusceptible to the antibiotic. The resistance gene enables bacteria to break down and destroy the antibiotic.

Where do antibiotic resistance genes come from?

Resistance genes may be present in bacteria that produce antibiotics or in bacteria that are naturally resistant to a given antibiotic. The special characteristic of these genes lies in the fact that they can be found on minichromosomes capable of passing from one bacterium to another. These resistance genes are thus described as being mobile. A bacterium can gain a resistance gene and become resistant to an antibiotic. It can also receive several resistance genes at once and become resistant to several antibiotics. Such microbes are referred to as multidrug-resistant bacteria.

Why are there more resistant bacteria in hospitals?

Hospitals are places where antibiotics are frequently used. Many patients are in a poor general condition or present with various diseases that make them prone to infection necessitating antibiotic treatment.

Such infections are caused either by bacteria like Escherichia coli that are found in various environments, or bacteria like Klebsiella pneumoniae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa that are more specific to hospitals. The so-called "golden staphylococcus", Staphylococcus aureus, is another classic example, causing infections that can sometimes be extremely difficult to treat.

Antibiotic resistance: a global problem?

Pathogenic bacteria are unrestricted by geographic borders. They move between countries, for instance when people travel. Although the situation is concerning in France, it is even more serious in other countries.

Antibiotic resistance is a global problem affecting humans, animals and the environment. Bacteria spread not only among humans, but also between humans and animals. Resistance genes can also circulate in the environment. As such, a "One Health" approach is applied to elucidate the phenomenon of antibiotic resistance in the three fields of human, animal and environmental health.

How can we use antibiotics properly and tackle antibiotic resistance?

- Complete the course of treatment to ensure that all the bacteria responsible for your infection have been eliminated, allowing you to make a full recovery and avoid any relapses.

- Do not self-prescribe antibiotics: antibiotics should only be taken with a medical prescription. Antibiotics only work on bacteria, so if you use a previously prescribed antibiotic to treat a viral illness, it will not work and will also encourage the multiplication of resistant bacteria.

- Limit infections. This is primarily achieved through health and hygiene measures and particularly through hand washing. Vaccination also has a knock-on effect, since vaccines against viruses such as influenza prevent people from getting sick and acquiring secondary infections requiring antibiotics.

What to do if antibiotics don't work?

One possible reason the antibiotics aren't working is that you have a viral infection. Antibiotics are only effective against bacteria, so it's inevitable that your infection will not respond to antibiotic treatment.

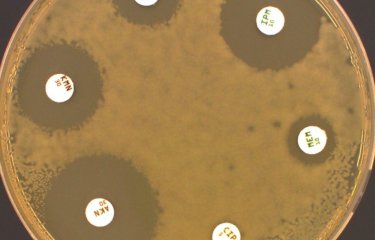

You may also be infected with an antibiotic-resistant bacterium. In this case, the bacterium needs to be isolated and analyzed to determine which antibiotic the bacterium is susceptible or resistant to, and then choose the antibiotic to which the bacterium is susceptible. This test, called an antibiogram, is carried out every day in hospital laboratories.

October 2024