Despite its apparent simplicity – a tube-like body topped with tentacles –, the sea anemone is actually a highly complex creature. Scientists from the Institut Pasteur, in collaboration with the CNRS and the Weizmann Institute of Science, have just discovered over a hundred different cell types in this small marine invertebrate as well as incredible neuronal diversity. This surprising complexity was revealed when the researchers built a real cell atlas of the animal. Their findings, which will add to discussions on how cells have diversified and developed into organs during evolution, have been published in the journal Cell.

The sea anemone Nematostella vectensis provides a perfect model for researchers – apart from its stinging tentacles perhaps. It is a small marine invertebrate that is easy to keep in the laboratory and whose genome is simple enough to study its workings and close enough to that of humans for conclusions to be drawn. "When the sea anemone genome was sequenced in 2007, scientists discovered that it was very similar to the human genome, both in terms of the number of genes (roughly 20,000) and its organization, explains Heather Marlow, a specialist in developmental biology in the (Epi)genomics of Animal Development Unit at the Institut Pasteur and the main author of this study. These similarities make the sea anemone an ideal model for studying the animal genome and understanding interactions existing between genes". It also has another advantage – its strategic position in the tree of life. The cnidaria branch that anemones belong to separated from the bilateria[1] branch, in other words from most other animals, including humans, over 600 million years ago. "The anemone can therefore also help us to understand the origin and evolution of the multiple cell types making up the bodies and organs of animals, and particularly their nervous systems", sums up Heather Marlow.

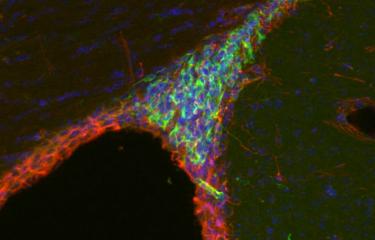

To try and understand a little more about sea anemones – and consequently about the whole animal kingdom –, Heather Marlow's team decided to examine this cnidarian, cell by cell. Thanks to an innovative technique, the animal's tiny cells – that measure no more than 1 micron in diameter – were isolated one by one, and their RNA analyzed. As although chromosomal DNA contains all genes, RNA shows those that are active. "The development of genome approaches at single-cell level can be used to accurately list the different cell types and also identify the genes responsible for the function of each of these cells", explains Heather Marlow. In total, and unexpectedly, over a hundred different cell types were identified, grouped into eight main cell families (muscle, digestive, neuronal, epidermal, etc.). And one of the greatest surprises of this research concerns the nervous system. Close to thirty different types of neurons – peptidergic, glutamatergic or even insulinergic – were identified, revealing a relatively complex nervous and sensory system.

This research should therefore help evolution specialists to establish the common ancestor of cnidaria (anemones) on the one hand and bilateria (humans) on the other. Undoubtedly this ancestor already had some level of cell complexity. In addition, even though the sea anemone appears to be very different from us, it reveals the fundamental rules that today enable its cells, and our own, to perform so many different functions. "The cell is the basic element making up living beings". By defining how the information coded by the genome determines the identity of each cell, we hope to uncover the mechanisms conserved by all animals that are essential for their development and homeostasis[2]", concludes Heather Marlow.

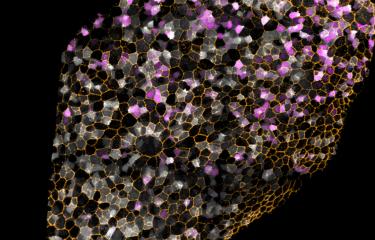

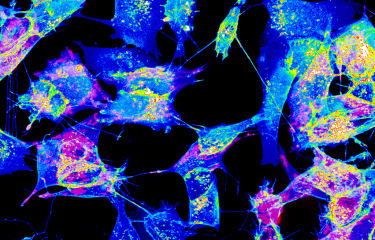

(right): a sea anemone, Nematostella vectensis. (center) Living (green) and dead (red) cells isolated after dissociation. (left) N. vectensis neurons revealed by the specific expression of a transgenic marker. © Institut Pasteur

[1] Organism with left-right symmetry.

[2] Ability of a system to maintain a stable internal environment.

Source

Cnidarian Cell Type Diversity and Regulation Revealed by Whole-Organism Single-Cell RNA-Seq, Cell, May 31, 2018

Arnau Sebé-Pedros (1), Baptiste Saudemont (2,3), Elad Chomsky (1), Flora Plessier (2,3,4), Marie-Pierre Mailhé (2,3), Justine Renno (2,3), Yann Loe-Mie (2,3), Aviezer Lifshitz (1), Zohar Mukamel (1), Sandrine Schmutz (5), Sophie Novault (5), Patrick R.H. Steinmetz (6), François Spitz (2,3), Amos Tanay (1,7,*) and Heather Marlow (2,3,*)

(1) Department of Computer Science and Applied Mathematics and Department of Biological Regulation, Weizmann Institute of Science, 76100 Rehovot, Israel

(2) (Epi)genomics of Animal Development Unit, Department of Developmental and Stem Cell Biology, Institut Pasteur, 75015 Paris, France

(3) CNRS, UMR3738, 25 Rue du Dr Roux, 75015 Paris, France

(4) Département de Biologie, Ecole Normale Supérieure de Lyon, 46 Allée d’Italie, 69364 Lyon Cedex 07, France

(5) Cytometry & Biomarkers UtechS, Cytometry Platform, Institut Pasteur, 75015 Paris, France

(6) Sars International Centre for Marine Molecular Biology, University of Bergen, Thormøhlensgate 55, Bergen 5006, Norway

(7) Main author