When HIV emerged in the early 1980s, it unleashed a tidal wave of devastation which continued until the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy in 1996. Tools to tackle the virus gradually began to be developed, and patients can now live with HIV. But what is the situation today? The Institut Pasteur held a conference from November 29 to December 1, 2023 to review the progress that has been made in the response to HIV. This article summarizes some of the information presented at the conference.

| This report was produced with the help of Tania Louis, scientific mediator and educational content designer, who also produced a video summarizing some of the symposium's highlights. |

On June 5, 1981, a medical surveillance report described the situation of five men who had been admitted to hospital in Los Angeles. They were all homosexuals and had been diagnosed with cytomegalovirus infection, mucosal candidiasis and, most importantly, a form of pneumonia generally associated with severe immunosuppression. These were the first identified cases of a disease which, by late 1982, had been named AIDS: acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. AIDS is caused by HIV, or human immunodeficiency virus, identified at the Institut Pasteur in early 1983. Forty years have passed since then, and the goal of eliminating the AIDS pandemic by 2030 no longer seems like a pipe dream.

AIDS is a disease caused by HIV, which generally occurs several years after infection. In the intervening period, infected individuals are largely asymptomatic. So while all people with AIDS carry HIV, the reverse is not true: it is entirely possible to be a carrier of HIV without having AIDS. Current treatments enable people infected with HIV to control the virus with no risk of transmission or progression to AIDS.

1981-1996: a dark period

The first 15 years of the HIV pandemic were characterized by a paradox: while rapid progress was being made in research laboratories, hospitals were facing a drastic situation. Although the receptor used by the virus had been identified, the viral genome had been sequenced and the first diagnostic tests had been developed, infected individuals continued to be diagnosed after the onset of AIDS, when they were already suffering from a deadly, uncontrollable disease. In 1986, an HIV diagnosis meant an 85% probability of death within the next five years.

Room at Hôpital Pasteur after 1983 © Institut Pasteur

Room at Hôpital Pasteur after 1983 © Institut Pasteur

The disease particularly cut a swathe through the gay community, whose members now had to deal not only with homophobia but also with the agony of seeing friends die, the torment of wondering whether they would be next on the list, and a new form of stigma imposed by a terrified society. Before the invention of the term "AIDS," the disease was known by several other labels, including "gay plague," "gay cancer" and "4H disease" (because it seemed to affect homosexuals, heroin users, hemophiliacs and Haitians). This bleak context led to a surge in activism, resulting in the launch of charities such as AIDES in France and the global Act Up movement, and giving those affected by HIV greater agency in their fight against the virus.

Discover Dr. Anthony Fauci's inspiring speech at the Institut Pasteur, marking the 40th anniversary of the groundbreaking discovery of HIV. As a key figure in the fight against HIV/AIDS, Dr. Fauci shares his personal journey, reflecting on the evolution of the epidemic from its early days to the present. This speech offers a unique perspective on the enduring quest for solutions in the battle against HIV/AIDS © Institut Pasteur

Find out about Françoise Barré-Sinoussi's memories of the discovery of HIV and her links with patient associations.

Charities and other organizations have played a key role in the fight against HIV. The Institut Pasteur was keen to give representatives of these charities an opportunity to share their thoughts:

- Pauline Londeix, former Vice-President of Act Up-Paris and co-founder of the Observatory for Transparency in Drug Policies (OTMeds). In 1983, there was no treatment, and people infected with HIV generally died from AIDS. But in 1996, highly-active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) was introduced in the Global North, before becoming available in the Global South from 2001 onwards.

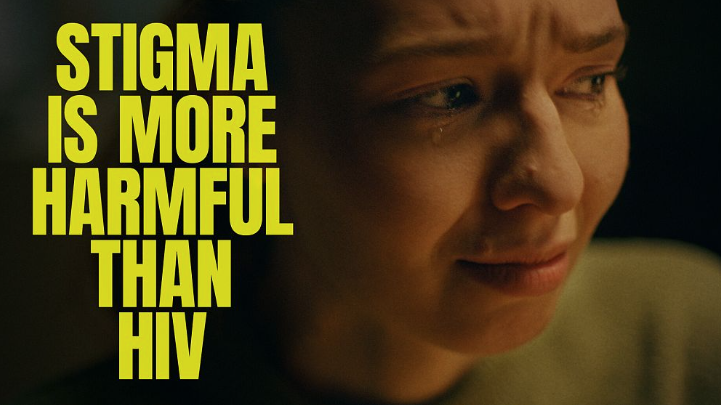

- Florence Thune, Executive Director of Sidaction. In the 1980s, there were widespread misconceptions of the virus and the way it was transmitted, and people living with HIV were the target of considerable discrimination. Today, huge strides have been made in science and knowledge. But the stigma hasn't gone away.

- Jennifer Pasquier, Scientific Director at Sidaction. HIV, which was completely unknown in 1983, was a source of fear and rejection for infected people. While there have been advances in scientific knowledge over the decades, there are still many misconceptions about HIV, especially among young people.

- Marc Dixneuf, CEO of AIDES. Today HIV-positive patients can live a relatively normal life with the virus if they are diagnosed in time and receive the right treatment. Treatments are constantly being improved, and great strides are being made as a result of close cooperation between people with HIV, caregivers and scientists.

We condemn attempts to label us as "victims," a term which implies defeat, and we are only occasionally "patients," a term which implies passivity, helplessness, and dependence upon the care of others. We are "People With AIDS."

The first paragraph of the Denver Principles, written in 1983 by the Advisory Committee of People with AIDS (see below)

In 1987, the first drug with an effect on HIV was identified and marketed. In that same year, the "Silence=Death" visual and slogan were launched as an attempt to raise awareness of the urgency of the situation of those affected by the virus. How could the usual lengthy time frames for clinical trials be acceptable when people were dying every week, every day? Compassionate use of treatments with uncertain efficacy was eventually authorized.

In France, the "Treatment and Therapeutic Research" group (TRT-5, in French), a coalition of five associations, was established in 1992 as an advocacy and information platform for people affected by HIV. It continues to work in close partnership with ANRS-Emerging Infectious Diseases. Finally, in 1996, combinations of three drugs targeting different components of HIV were developed. They had to be taken for life, but these treatments, known as highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), were the first reliably effective tool in tackling AIDS. After 15 devastating years, the death rate finally began to recede. But there was still a long way to go.

AIDS is a fatal disease caused by HIV, and while it can now be prevented, there is still no cure. But there have been six reported cases of people with HIV who have been able to stop antiretroviral treatment after receiving bone marrow transplants. Since it is impossible to fully demonstrate that there are no traces of the virus left in their body, caution prompts us to speak of "remission" rather than "cure." Whether or not HIV has actually been entirely eliminated, these cases prove that it can be blocked.

Bone marrow transplants, used as a treatment for people with cancer, are much too onerous and risky to be adopted as a widespread therapeutic approach. But there are also a handful of individuals (less than one percent of all those with HIV) known as "natural controllers," who are capable of spontaneously controlling HIV in the absence of any treatment. Research into the immune and other mechanisms involved in these phenomena of HIV resistance offers hope of new therapeutic avenues that might improve the situation of all those affected by the virus.

Treatment and prevention: an increasingly effective battle against HIV

There are two broad approaches to preventing transmission of a virus: the first is to stop infected people from being contagious, and the second is to give uninfected people the ability to resist contamination. In the fight against HIV, significant progress has been made on both fronts since 1996.

Current antiretroviral treatments enable people living with HIV to control the virus and to reduce their viral load to undetectable levels, less than 200 copies per milliliter of blood. Several studies (Rakai, HPTN 052, PARTNER 1 and 2, Opposites Attract, Partners PrEP, etc.) have demonstrated that these people are no longer contagious at all. The aim of the U=U campaign (Undetectable=Untransmittable) is to raise awareness of this major breakthrough. HIV treatment is therefore now considered as a form of prevention, an example of the concept of "treatment as prevention" (TasP).

Other trials, especially the ANRS-IPERGAY trial in France, have proven that people without HIV can avoid infection by taking antiretroviral drugs. This principle, now known as PrEP, or pre-exposure prophylaxis, was included in the recommendations of the World Health Organization in 2015. PrEP can be taken on a continuous basis or as a one-off, just before and after potential exposure to HIV. EPI-PHARE data (in French) show that in real-life conditions in France, PrEP offers 93% protection when taken as prescribed.

Emergency treatment can also be taken within 48 hours of exposure to HIV to try to prevent infection.

The first highly active antiretroviral therapy revolutionized HIV treatment, but it was particularly burdensome. It had multiple side effects, and as it was customized to overcome viral resistance as effectively as possible, some patients were required to take dozens of pills every day. In France and other developed countries, HIV can now be treated with a single tablet a day, or even with injections every other month. The side effects are also much milder. All of these improvements make it much easier for patients to stick to a treatment regimen and therefore control the virus.

It is currently recommended that people with HIV begin treatment as soon as they are diagnosed – firstly to stop them from being contagious, and secondly because treatments are more effective if taken early. But this was not always the case: before 2015, criteria including clinical situation and CD4 cell count were taken into consideration when deciding when to start treatment.

Improving the accessibility of HIV testing and treatment

All these breakthroughs, together with a solid understanding of the mechanisms of transmission and behavioral prevention strategies like the use of condoms, could in theory bring HIV to an end. But there is still a long way to go, including in developed countries: more than 5,000 people were diagnosed with HIV in France in 2021, nearly a third at an advanced stage of infection.

© AdobeStock/ Lightfield Studios

© AdobeStock/ Lightfield Studios

The aim of implementation science is to promote the transfer of scientific developments to policies and health care practices. The results obtained in this area are crucial: the very best treatment will be useless if it is not distributed effectively or accepted by those who need it.

The situation with PrEP in France shows that it is not just because a tool is available that it will be used. PrEP has been available by prescription since early 2016; it is fully refunded and is free at point of access from CeGIDD branches (centers for information, testing and diagnosis) in France. But of all those diagnosed with HIV between April 2019 and November 2020, while 91% were eligible for PrEP, only 11% made use of it. Although 75% were aware of PrEP, many did not opt to use it for various reasons, the most common being that they were afraid of side effects, they did not perceive HIV as a risk, they were not offered PrEP or did not know how to access it, or they discovered that they were HIV positive when they wanted to start taking PrEP.

A preventive approach will only ever be effectively adopted if it is widely known and easy to implement. The European Commission recently granted marketing authorization for PrEP that is administered by injection every two months. The CaboPrEP clinical trial, which will test the effectiveness of this PrEP in France, is set to begin in early 2024.

Adapting to local situations to tackle HIV effectively

What makes the fight against HIV more complicated is the fact that the pandemic conceals a wide variety of different situations, each of which needs to be approached in a different way. Viral strains in circulation, opportunistic infections that occur in people with weakened immune systems, the genetic profile of those affected, the populations most exposed to the virus, living conditions and available medical tools vary from one place to another, so strategies need to be tailored to local situations. This applies both to research – clinical trials are mostly conducted in Europe or the United States, despite the fact that three-quarters of people living with HIV are in Africa or South-East Asia – and to implementation, the aim being to offer appropriate solutions to each individual.

For example, while women currently represent just 30% of new cases of HIV infection in France, at global level 53% of people living with HIV are women. Women aged 15 to 25 are disproportionately affected in regions where the virus is in active circulation. The profile of at-risk communities that could benefit hugely from the protective effect of PrEP is therefore very different in France, where PrEP is used almost exclusively by men having sex with men, and in Africa, where projects like the DREAMS partnership are aimed at teenage girls and young women. This has resulted in two different strategies: PrEP is offered in tablet form in France, while long-acting vaginal rings are recommended in Africa.

PrEP, a preventive treatment to avoid HIV contamination, but which does not protect against other sexually transmitted diseases © AdobeStocka/ alimyakubov © AdobeStocka/ alimyakubov

PrEP, a preventive treatment to avoid HIV contamination, but which does not protect against other sexually transmitted diseases © AdobeStocka/ alimyakubov © AdobeStocka/ alimyakubov

Women are more susceptible than men to autoimmune diseases and respond better to vaccination. In general, biological sex and gender stereotypes (when it comes to factors such as diet, exercise and smoking) influence the way the immune system works, and that has consequences in the event of HIV infection. Women infected with HIV have a stronger immune response than men; they control the virus more effectively in the acute phase of infection and the viral reservoir when treated, but they progress to AIDS more quickly in the absence of treatment.

This can partly be explained by the fact that several genes which regulate the immune response are located on the X chromosome. Women have two X chromosomes and men only have one, and even though a copy of the X chromosome is inactivated in female cells, some genes evade this process and are over-expressed in women. The stronger immune activation in women is also partly hormonal, since testosterone has an inhibitory effect and estrogen has an activating effect.

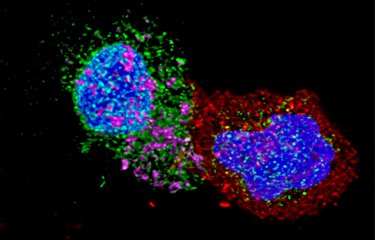

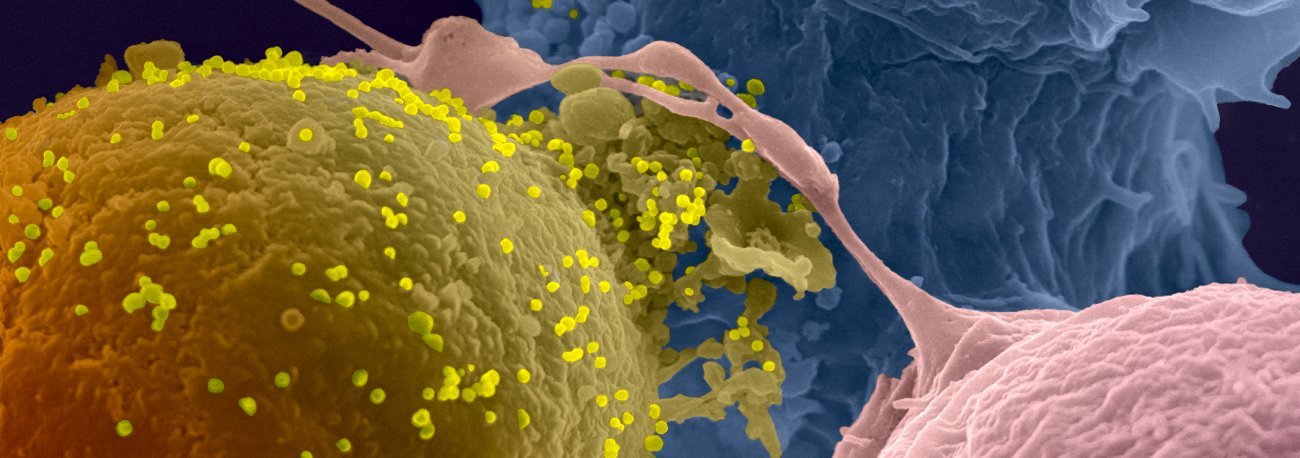

Cell-to-cell transmission of HIV-1. HIV-1-infected lymphocyte (in yellow) in contact with uninfected lymphocytes (in blue and pink). Viral particles are in light yellow. Scanning electron microscopy photo © Institut Pasteur/Olivier Schwartz, Virus and Immunity Unit - Ultrastructural Microscopy Platform - Colorization Jean-Marc Panaud.

The need for vulnerable populations to have access to existing tools

Inequality is also a major challenge in the fight against HIV, and progress is still needed in this area. In several countries, including developed countries, the populations most affected by HIV are already marginalized for other reasons, which may include sexual orientation and practices, gender, ethnic origin, drug use, profession or migratory status. Tackling HIV requires an intersectional approach to discrimination and the involvement of affected communities. While some communities have been active since the start of the pandemic, others remain cut off from health care systems. In France, although the number of infections among men who have sex with other men born in France has fallen since PrEP was introduced in 2016, this is not the case for men born abroad.

As well as these inequalities among population groups, there are also broader economic inequalities. Significant improvements were seen in this field in the early 2000s, with the distribution of less expensive generic treatments and the launch of funding initiatives such as the Global Fund and PEPFAR, aimed at countries with limited resources. So although logistical hurdles and a lack of local resources make managing the HIV pandemic a complex task in the areas where it is most prevalent, research and health care are developing in Africa. And while access to treatment remains a challenge in several regions, it is worth pointing out that in 2022, only five countries worldwide had reached the threefold target set for 2030 – 95% of people with HIV knowing their HIV status, 95% of people diagnosed with HIV receiving treatment, and 95% of people on treatment being virally suppressed: Botswana, Eswatini, Rwanda, Tanzania and Zimbabwe. All of those countries are in Sub-Saharan Africa.

The close association between HIV and already stigmatized communities represents a huge problem in all world regions since it creates an obstacle to testing, for at least three reasons. First, some at-risk individuals are scared to be tested because they are afraid of being associated with a stigmatized community in their local area. Second, people who are already cut off from the medical system are not necessarily aware of their rights and do not always know how to get tested if they need to. Finally, people who are not part of these communities associated with HIV do not see the virus as something that concerns them and do not take steps to protect themselves or get tested, even though they should do. For example, in France today, half of all those infected with HIV catch the virus following heterosexual intercourse.

Testing is a crucial part of the fight against HIV, on both an individual and a collective level. Receiving a diagnosis means that treatment can be started as soon as possible, thereby improving the situation of people with the virus and also preventing them from passing it on. In France, testing is available free of charge and without an appointment at all medical laboratories, and self-tests can be bought at pharmacies. But it is thought that some 24,000 people living with HIV are currently unaware that they have the virus.

It is important to bear in mind that people living with HIV continue to face significant discrimination, which is an additional hurdle to testing. As proof that education about HIV is still needed, 29% of parents believe that HIV-positive people represent a risk for their children, and 17% of the workforce would be uncomfortable to learn that one of their colleagues is HIV positive.

Source: 2021 survey by the HIV charity "Crips Île-de-France" (in French)

Genetic diversity and viral reservoirs: two obstacles yet to be overcome in the fight against HIV

With diagnostic tests, treatments that control the virus and prevention techniques including pre-exposure prophylaxis, we now have a powerful toolkit to tackle HIV, and the contribution of implementation science is constantly improving the effectiveness of these approaches. But unequal access and stigma are two obstacles that continue to be difficult to overcome. And there are also two challenges that research has as yet been unable to resolve: 40 years after the discovery of HIV, there is still no vaccine for the virus, and there is no treatment that actually cures it.

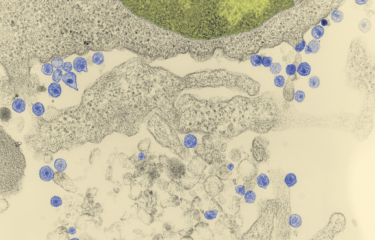

AIDS virus (HIV) particles budding from the surface of a CD4 T lymphocyte. Scanning electron microscopy. Colorized image © Institut Pasteur/Marie-Christine

AIDS virus (HIV) particles budding from the surface of a CD4 T lymphocyte. Scanning electron microscopy. Colorized image © Institut Pasteur/Marie-Christine

The extreme genetic diversity of HIV has made vaccine trials difficult. In some patients, the diversity of the virus is comparable to that of influenza at global level! This also raises problems in terms of treatments: mutations of HIV increase the risk that it will develop resistance as soon as it has the opportunity to proliferate. HIV is a master of evasion, establishing itself inside the DNA of infected cells and forming what are known as reservoirs – cells carrying the virus that are hidden in the body. In the absence of treatment or if treatment is interrupted, these cells serve as a starting point for HIV to begin proliferating again. It is these reservoir cells that stop us from being able to cure HIV, and they are the focus of much research. Two main strategies are being explored to target them: forcing them to express the virus they contain so that they can be identified and destroyed (the "shock and kill" approach), or permanently silencing them so that they can no longer produce the virus (the "block and lock" approach). An early-stage clinical trial is currently under way based on a third strategy that uses CRISPR molecular scissors to extract the viral genome of reservoir cells and attempt to eliminate the virus from the body.

After receiving antiretroviral treatment, some people infected with HIV become capable of controlling the virus. These individuals are able to discontinue their treatment without viral rebound – some stopped treatment more than twenty years ago. These cases of functional remission confirm the potential of "block and lock" strategies in tackling reservoir cells.

Several post-treatment controllers are currently being monitored as part of the VISCONTI cohort. Early treatment with antiretrovirals, in the first weeks after infection, is key to this form of remission. Research programs like the RHIVIERA trials are under way to shed light on the various factors behind post-treatment control.

Novel therapeutic approaches derived from basic research

The composition of highly active antiretroviral therapy varies from one patient to the next, but it currently tends to combine inhibitors of different stages of the HIV replication cycle: reverse transcriptase inhibitors, protease inhibitors, integrase inhibitors and fusion inhibitors, the latter preventing the virus from entering cells. But recent progress in basic research has paved the way for novel therapeutic approaches.

Natural killer (NK) immune cells are naturally capable of controlling infection in some monkeys but not in humans. Stimulating these cells could help to reduce the establishment of viral reservoirs in the lymph nodes, where they are active. This immunotherapy approach is currently being explored at the Institut Pasteur.

Intestinal cells producing a cytokine conferring protection against AIDS in African green monkeys infected with simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) © Institut Pasteur/Nicolas Huot

Intestinal cells producing a cytokine conferring protection against AIDS in African green monkeys infected with simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) © Institut Pasteur/Nicolas Huot

Broadly neutralizing antibodies (bNAbs), also part of the immune system, are particularly promising. These proteins recognize a wide range of HIV variants and are produced by rare patients who are spontaneously capable of controlling the virus after infection. They are the focus of considerable research because they perform multiple functions: they are capable of blocking infection, activating the immune system, marking viral particles for destruction and eliminating infected cells. They seem to reduce the viral reservoir, and they may even offer a novel vaccine strategy: inducing bNAb production through vaccination could neutralize the advantage conferred on HIV by its extreme genetic diversity. Finally, the effectiveness of lenacapavir, an HIV capsid inhibitor, has recently been proven. The capsid protein had not previously been targeted for treatment purposes, and this newcomer in the therapeutic arsenal is particularly useful in the event of resistance to conventional treatments. It also has another clear advantage: it is effective over the long term, and when dosed correctly it may only need to be administered as an injection every six months.

In this video, Tania Louis, scientific mediator and educational content designer, summarizes the involvement of people living with hiv, the situation in France today and recent discoveries ©Tania Louis (in french)

The development of long-acting compounds, whether treatments or pre-exposure prophylaxis, is now a priority. Offering alternatives to daily tablets could reduce stigma, avoid missed doses and make it easier to treat and monitor populations in remote areas with difficult access to health care. Several options are currently the focus of research, including lenacapavir, cabotegravir, ibalizumab, islatravir and MK-8527.

But for each new compound, clinical trials are needed to identify effective administration regimens. And there are multiple parameters to take into account, such as dosage, combination with other molecules, frequency of doses, and the emergence of resistance. Two limiting factors in particular need to be borne in mind. First, trials currently involve people who already control HIV as a result of previous treatment. The effectiveness of long-term treatment also needs to be assessed in newly diagnosed individuals. Second, compounds that are active for several weeks are generally administered by injection by medical professionals, which makes them less accessible. The development of long-acting oral tablets would represent a significant breakthrough.

For people living with HIV, quality of life still needs to be improved

Although current treatments mean that HIV can be kept under control, it is hoped that further progress will improve the quality of life of people living with the virus. Long-acting compounds that reduce the frequency of doses will be crucial in reducing the mental burden and stigma while facilitating adherence to treatment, including for marginalized populations. It goes without saying that efforts continue to be needed to reduce the side effects associated with treatment. And the many comorbidities associated with HIV and antiretrovirals must not be neglected, including those associated with living with the virus and the impact on mental health. Living with HIV is a psychosocial risk factor that is aggravated by discrimination, including in medical settings. People with HIV are more prone to depression than the general population.

To help meet the needs of people living with HIV, we need to listen to what they have to say. This is the aim of the VESPA surveys (in French), the third round of which is currently under way in France. Clear targets in the fight against HIV have been set in terms of testing, treatment and viral load control. The idea of adding a target regarding the quality of life of people living with HIV is sometimes put forward as a way of improving the situation.

© 2022 by Enquête VESPA 3 (in french)

© 2022 by Enquête VESPA 3 (in french)

The life expectancy of people with HIV is now comparable with that of the general population, and it has become possible to grow old with the virus. Indeed, estimates suggest that a quarter of people living with HIV are now aged 50 or over. But they live fewer years in good health, experiencing comorbidities associated with aging earlier than other people.

We need to provide better support for these individuals by adapting treatment and monitoring as they get older, improving the detection and prevention of diseases that can be avoided, and continuing to combat stigma. Basic research is also crucial to develop treatments that meet the needs of increasingly elderly people living with HIV.

Making progress accessible and adapting it to the needs of each individual

Forty years on from the discovery of HIV, our understanding of the virus is constantly improving. The development of the first treatments transformed what was once a life sentence into a chronic disease, and today it is possible to live with HIV but without AIDS. Although there is no vaccine, pre-exposure prophylaxis has considerably improved the preventive arsenal available to us. And the emergence of new approaches and long-acting drugs, whether for treatment or prevention, is hugely promising, to such an extent that the target of eliminating AIDS by 2030 seems possible.

But if we are to reach it, the existing tools need to be made available and tailored to the needs of each individual affected by HIV. And that means all of humanity, in all its diversity: people living with the virus so that they can be treated and avoid passing it on, people without HIV so that they can avoid catching it, and each and every one of us so that we can tackle the wide-ranging discrimination that continues to fuel the pandemic and the suffering it causes. This will require a concerted, coordinated effort, including in financial and logistical terms, and due consideration will also need to be given to research in humanities and social sciences, especially in the field of implementation. It is a huge challenge.